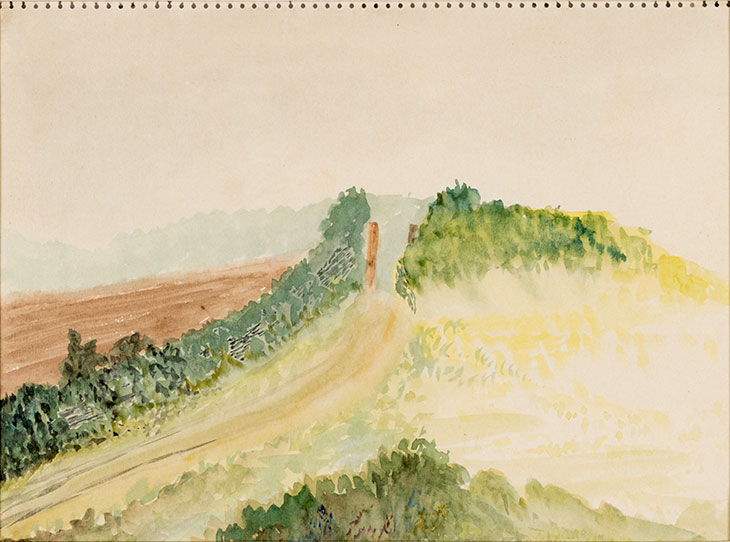

The painting that opens the De La Warr Pavilion’s exhibition ‘A Tale of Mother’s Bones: Grace Pailthorpe, Reuben Mednikoff and the Birth of Psychorealism’ – Pailthorpe’s May 23, 1935 (Pathway through Fields) – is a bold choice, not in spite of its apparent unremarkability but because of it. This rapid, unfinished watercolour landscape on notebook paper (the holes for the ring binding are visible along the top) shows a country road cresting a hill between hedgerows. Yet, within the distinctive artistic sensibility developed by Pailthorpe and Mednikoff, her long-term collaborator, even the most mundane artistic surfaces are intimate in their psychological depth. In this case, one hasn’t far to search for such depth since both Pailthorpe and Mednikoff inscribed the verso of the picture with their interpretations of it, and here the curators have displayed the painting so we can read them. For Mednikoff, who was trained as a painter, the landscape marked a development in Pailthorpe’s capacity to ‘use watercolour without any feeling of restriction’. For Pailthorpe, trained as a psychoanalyst and a surgeon, it was a representation of ‘the whole earth giving birth’.

May 23, 1935 (Pathway through Fields) (1935), Grace Pailthorpe. Courtesy The Haines Collection

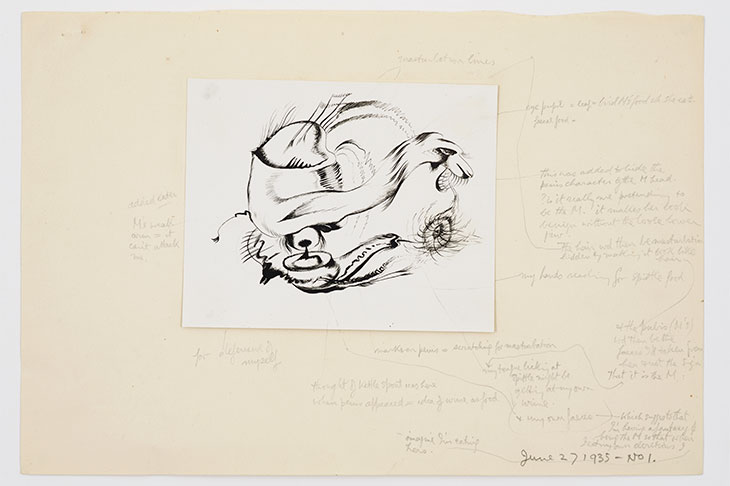

If experience and its interpretation were inseparable for Pailthorpe and Mednikoff (as their portmanteau coinage ‘Psychorealism’ suggests), so were theory and practice. The extensive collection of notes, scrapbooks, manuscripts, and sketches on display here shows the pairing of artworks with interpretive context to be typical of their shared methods: paintings and drawings were photographed and annotated, and extended lectures were composed on the subject of single works. One of the few works kept on display in the artists’ home, Mednikoff’s oil of a moustache-twirling tiger in military regalia, December 25, 1945 – January 18, 1947 (The Bengal Colonel), is unusual in lacking an official interpretation, though visitors would unfailingly be instructed by Pailthorpe and Mednikoff to ‘look in its mouth’ in order to test their own interpretative faculties. In addition, then, to recovering from obscurity an astonishing array of pictures, many of which have not been viewed together since the early 20th century, the exhibition permits the curators to make a strong case for integrating the lifelong project of interpretation undertaken by Pailthorpe and Mednikoff with their paintings and drawings.

Taken individually, the symbolisms with which the artists invest their work are startling in their frank fascination with the body – with copulation and birth, ejaculation and excretion. Indeed, Pailthorpe and Mednikoff thought of the works themselves as forms of excretion or, as they liked to put it, ‘venting’. At times smeary, and at times fastidiously disciplined, all of the styles represented here are positioned by the artists as attempts to represent and cope with childhood trauma, primarily the trauma of birth. As familiarity with Pailthorpe and Mednikoff’s strategies grows, this interpretive urge can begin to read like its own form of disciplinary practice, cuing the viewer to discover homogeneity in spite of the otherwise strong tendency of their work toward variety, divergence, mutation.

September 10, 1936 (The Flying Pig) (1936), Reuben Mednikoff. Collection of Michel and Susie Remy, Nice

Pailthorpe and Mednikoff were radical in their politicisation of art: ‘Hitler and Mussolini’ would, they argued, ‘never have become insanely dictatorial had they had, as children, ample opportunity to vent their infantile rages’ by painting. Nevertheless, as the curators demonstrate, the hermeticism of the artists’ thought at times led to disturbing political blindnesses (non-white figures in Mednikoff’s work are, for instance, judged to be emanations of his inner baby). While they were delighted to be called by André Breton the ‘best and most truly Surrealist’ English contributors to the 1936 International Surrealist exhibition, interpretation proceeds here largely outside the context of art history. And the habit of discovering in every artwork evidence of the original, even idiosyncratic, strand of psychoanalytic theory developed by the artists themselves risks exchanging criticism for omphaloskepticism.

While this kind of inwardness certainly produces its own forms of inattention, it also leads Pailthorpe and Mednikoff to devote attention to experiences that have escaped others. This is particularly striking in the case of their intense consideration of often taboo aspects of birth, infancy, and motherhood. Family dramas of resentment and desire routinely mark the work of both artists. September 10, 1936 (The Flying Pig), for instance, was thought to suggest Mednikoff’s hunger for his mother as well as his resentment of infant competitors for her attention, while bed-wetting (Mednikoff’s March 20, 1936 – 1 (The Stairway to Paradise)) and maternal farting (June 13, 1935 – 4 (The Veil of Autumn / Autumn Mists) by Pailthorpe) were also viable themes. Pailthorpe’s pictures of birth, such as May 7, 1938 (Sea Urchin / The Escaped Prisoner), and her investigation of its traumas and significances, seem to me especially unusual and original in their attempt to recover the experience of the baby herself.

May 7, 1938 (Sea Urchin / The Escaped Prisoner) (1938), Grace Pailthorpe. Collection of James Birch

More than anything else, however, what Pailthorpe and Mednikoff are uniquely attentive to is one another. Their works are fascinating in part because they so powerfully testify to an artistic practice that could not exist without collaboration. Paul Ricoeur famously included psychoanalysis in what he called the hermeneutics of suspicion. Pailthorpe and Mednikoff demonstrate that, on the contrary, hermeneutics can be a form of commonality. Towards the end of his life, Mednikoff worried in his diary entry about what life would be like without Pailthorpe: ‘It means being left alone, defenceless, & without the loving mother-womb person. She is the only one who really understands my needs’. In their hands psychoanalysis becomes, through repeat applications, expositions, and discoveries, a form of intimacy.

‘A Tale of Mother’s Bones: Grace Pailthorpe, Reuben Mednikoff and the Birth of Psychorealism’ is at the De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill on Sea, until 20 January 2019. The exhibition will be presented at Camden Arts Centre from 12 April–23 June.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?