From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In the 1960s, an interesting series of experiments took place under the Soviet psychologist Alfred Yarbus, who was trying to assess how the human eye processes images. He had his subjects look at figurative paintings and traced which parts of the paintings attracted the most attention. His results clearly showed that if you present viewers with a painting, without giving them any particular prompt or information, their attention goes instinctively to the faces in the picture. It’s the face, after all, that is key to decoding what is really going on.

Hundreds of years before Yarbus’s experiments, some artists were very much aware of the pictorial power of the human face – an awareness that found new and memorable expression during the Dutch Golden Age. Granted, ‘Golden Age’ is a contested term. The Dutch provinces, engaged in wresting independence from Spanish rule during the Eighty Years War (1568–1648), were undoubtedly experiencing a period of intense economic prosperity; even at the time, people were describing their era as a ‘golden age’. But there’s no getting away from the fact that the enormous level of wealth being amassed by the Dutch Republic – unheard of for a country of its size – was predicated on colonialism.

What’s less contested is the flourishing of the arts in the 17th-century Netherlands. Previously, when the provinces were still under Spanish rule, art would always be destined for the Church; artists stuck to altarpieces. But a growing class of merchants living in the cities, wanting to display their wealth through their art, took to decorating their urban palaces with commissions. The sheer number of clients and patrons created a vibrant art market. Artists felt increasingly able to experiment with new genres that were not intended to hang in churches and did not serve any liturgical purpose, particularly landscapes and still lifes.

There were a few names that would have rung a bell throughout the region in the early 17th century. Haarlem could boast Frans Hals, a portrait painter but also a painter of genre scenes, known for his virtuoso brushwork. In Utrecht, Caravaggisti such as Gerrit van Honthorst were making a name for themselves. But most famous of all was Rembrandt. Starting off in his hometown of Leiden as a student of Pieter Lastman, a painter of historical scenes, his earliest work was very clearly informed by his master, which was normal at the time. But already by the age of 19, in 1625, he had become a master himself, establishing his own workshop with Jan Lievens, another Lastman alumnus.

It is in dialogue with Lievens – they often painted similar subjects around that time – that Rembrandt found his own artistic identity. And over the next five years, he came into his own. He was mostly still painting on a smaller scale, since there was a tradition in Leiden of painting very finely, in a detailed and meticulous manner. But he was starting to develop the looser brushwork he has become known for.

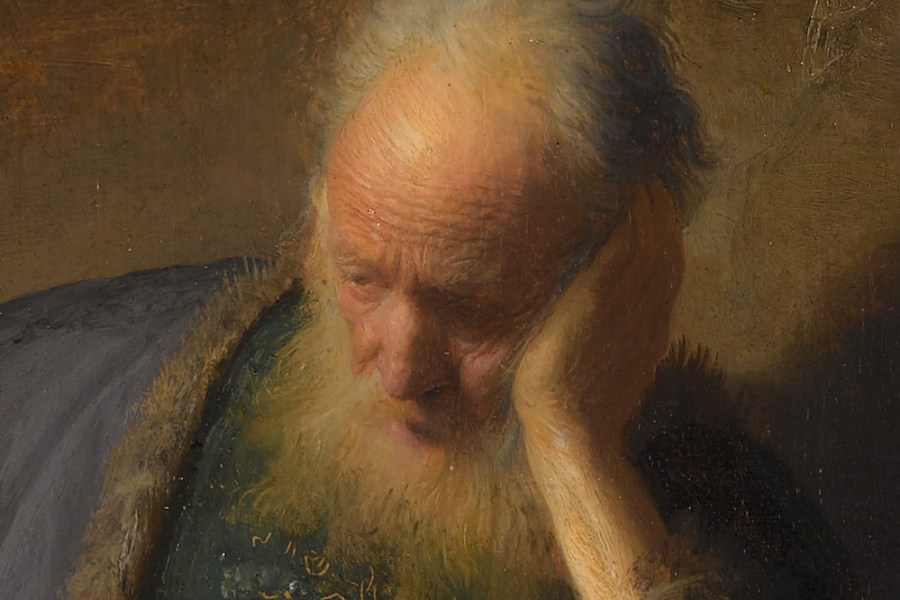

Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem (1630), Rembrandt. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Rembrandt would soon move to Amsterdam, where all the most important people (and merchants) lived. In 1630, a couple of years before his departure, he completed work on Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem. Jeremiah was an Old Testament prophet who witnessed the exile of his people, the Jews, to Babylon, where they were kept in captivity for generations, starting around 597 BC. Jeremiah is often referred to as ‘the weeping prophet’. He was woeful of the things that were happening to his people.

Jeremiah was not a common subject among painters. There was a tradition of depicting him as a mourning figure, for example in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes (1508–12), but Rembrandt’s treatment was quite novel. He situated Jeremiah in a wider story, fusing biblical lore, in which the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar destroyed the city of Jerusalem, with an account from the historian Flavius Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews (c. 94 AD), in which Jeremiah rescues some goods from the Temple of Solomon before it is sacked, and goes into hiding. Jeremiah, who only managed to escape because Nebuchadnezzar harboured a fondness for him, ended up in a cave, having preserved a Bible and some metalware from the temple. This is where Rembrandt’s painting finds him.

It may seem surprising that Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem was an important part of the Royal Museum of Fine Art Antwerp (KMSKA)’s recent ‘Turning Heads’ exhibition, which focused on tronies. Images of this genre, which emerged in the Low Countries in the 1500s, are depictions of heads – but they must be anonymous heads, depicting neither real people nor fictional figures. No painting or drawing of Jeremiah could ever be a tronie. Also, compositionally, tronies show the head alone. In 90 per cent of cases, they do so against a plain monochrome background, so there is only a face – no identity, no context. It is within the face that the story takes place. So it’s not about who is depicted in the tronie, it’s about what the person’s expression suggests, or how light defines their features, or the specific morphology of their face. Rembrandt’s Jeremiah, by contrast, is a history painting. Among the Old Masters, this was the highest category of painting; it consisted of depictions of stories that came largely from the Bible or from classical mythology, usually chronicling the great deeds of famous people.

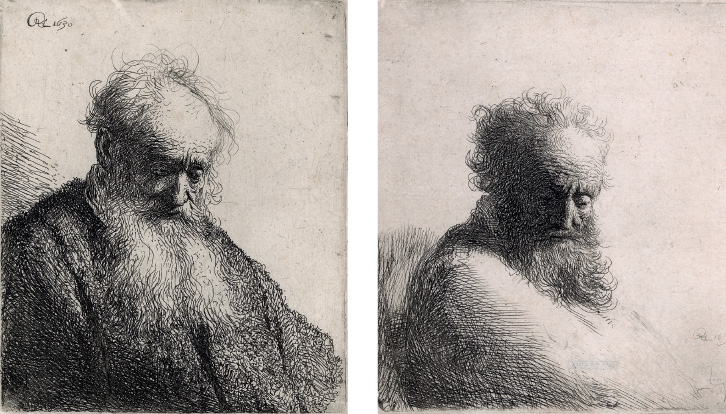

What is Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem doing in a show about tronies? In the exhibition, the painting is shown alongside four etchings of an old man, who is apparently the same model used for Jeremiah. In Jeremiah, the old man, with his deeply melancholy expression, is part of a larger story. In the etchings, we see what looks like the same person, but with no context at all – just his face. He’s not Jeremiah, he’s an anonymous man in whose face a whole story is taking place through fields of light and shade. These etchings are tronies, and show that the face alone can be art.

Old Man with a Long Beard and Old Man with a Long Beard Looking Down (both 1630) by Rembrandt. Museum Het Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam

The inclusion of history paintings such as Jeremiah in the show makes the case that even when artists weren’t painting tronies, they were intrigued by the human face. In history paintings, the best artists could make clear not only who the figures were meant to be, but also how they were feeling, how they were acting and reacting to each other or to circumstances. To this end, Rembrandt’s Jeremiah uses the picture plane remarkably; the most important part occupies such a small area of the painting. Generally speaking, if there is a figure in a painting, our eye is drawn to it. If that figure has a face, our eye is drawn there even before it appraises the figure, so in the empty expanse of space created by Rembrandt for Jeremiah, it’s Jeremiah’s face we single out immediately. Three hundred years before Yarbus’s experiments, Rembrandt knew that viewers would be attracted to faces.

Below the neck, too, Rembrandt’s Jeremiah has the bearing of someone lamenting from the depths of his soul. There was a common belief among history painters that what was going on in someone’s mind or spirit should be expressed through the movements of the body. This theory was first articulated by Leon Battista Alberti in the 15th century and pioneered by artists like Raphael. Then came the Mannerists, who pushed the borders further. But it was in the early 17th century that this kind of theatrical expressiveness really reached its peak. In Rembrandt’s vision, Jeremiah’s posture literally embodies his strong feelings.

The painter accentuates this by fixing a dramatic spotlight on the main figure. Rembrandt is known as a painter of light, and in this painting he handles it masterfully, from the rendering of atmospheric perspective to the specific textural effects of the light, including the illumination of Jeremiah.

Tied up with the subject matter here is that Rembrandt was known as a painter of the passions: he had a reputation for being able to depict profound emotions in a very moving way. It’s no wonder that Jeremiah, with his bottomless well of sorrow, appealed to Rembrandt. The resulting painting captures the figure’s feelings exceedingly well, even by the painter’s standards.

Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem (1630; detail), Rembrandt. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

There is another element of Jeremiah that is characteristic of Rembrandt: the brushwork, which has a very distinct facture. Though it’s not as blotchy as much of his later, more celebrated work, it’s clear that it was important to him to not just render a figure accurately, but also achieve something interesting in the surface of the paint itself. He has this way of painting the luminous parts in thick impasto – still quite fine, but noticeably thicker than in the shaded parts. This was fairly typical of 17th-century painting, but Rembrandt does it in a very refined way. He makes the paint surface shimmer.

He also has a way of contrasting the figure in the foreground with what is happening in the background, in the opening of the cave. The foreground is sharply rendered, with pronounced lines and edges, while the background, though still clear, is less defined, creating a mysterious sense of depth.

But Jeremiah’s clothing may be the most intriguing element of all – and not just because of the subtle textural differences in the fabric. The fur-lined garment he’s wearing is typical not of the biblical era, but of the 17th century, Rembrandt’s own time. It suggests, perhaps, that Jeremiah’s pain is timeless, echoing dolefully through the centuries.

As told to Arjun Sajip by Koen Bulckens, curator of Old Masters at Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten (KMSKA), Antwerp

‘Turning Heads: Rubens, Rembrandt and Vermeer’ is at the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, until 26 May.

From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home