From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

When we look at a Renaissance painting today, what do we actually see? Not, as one might hope, the authentic vision of the artist, the unsullied touch of the master. Alluring as this idea may be, we accept that the objects on the wall are not the perfectly preserved product of a historical moment, but at least in part the creation of conservators. The paintings we see are the work of many hands over many years, cleaning, retouching, varnishing – the results of repeated restorations.

While recent restorations are well documented and their consequences clear, it is the improperly understood impact of 19th-century interventions that is the subject of an important new book from the Getty Conservation Institute. The Renaissance Restored by Matthew Hayes, himself a practising conservator, investigates the way restoration developed as a professional, proto-scientific discipline. This development occurred alongside the expansion of the art market, the establishment of national museums and, importantly, as this book argues, in reciprocal relation with the discipline of art history. Divided into four case studies, two focused on particular artists, two on institutions, The Renaissance Restored examines the ‘epistemic implications’ of intervening in artworks, shedding new light on neglected practitioners while offering a fresh perspective on familiar art historians.

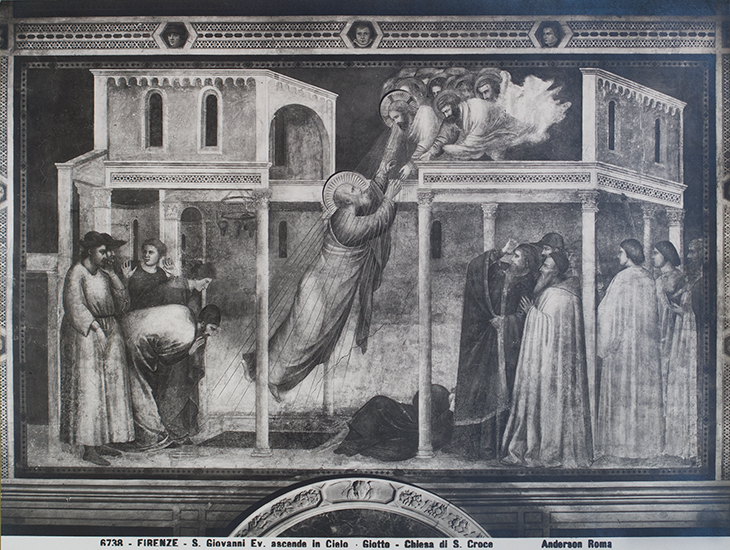

Nineteenth-century photograph of The Ascension of St John the Evangelist in the Peruzzi Chapel, as restored by Antonio Marini in 1848

Beginning in traditional fashion with Giotto, the first chapter looks at the recovery, restoration and outright recreation of several frescoes in Florence, most significantly those in the Bardi and Peruzzi chapels in Santa Croce. These had been plastered over some time in the mid 18th century, but were later uncovered in tandem with the renewal of interest in trecento artists: the Peruzzi between 1841 and 1863 by Antonio Marini and his pupil Pietro Pezzati, and the Bardi between 1851 and 1853 by Gaetano Bianchi. The work they carried out on the Santa Croce chapels remained, as Hayes writes, ‘an unavoidable mask’ for more than a century. Local retouching and broad toning went some way to disguising the damage caused by the excavation of the frescoes but, heeding their patrons’ concern for visual and narrative legibility, the restorers also completed major lacunae. What emerges from Hayes’ research is the status of the restorers as artists in their own right, wonderfully illustrated by fragments of these reconstructions which were removed in the 1950s and ’60s. We may doubt their historical accuracy but their skill is undeniable, and helps us understand Ruskin’s words on looking at an entirely invented Saint Louis on the east wall of the Bardi chapel: ‘Re-painted or not, it is a lovely thing.’

Head added to The Ascension of St John the Evangelist in the Peruzzi Chapel, Florence, 1841–48 by Antonio Marini; removed by Leonetto Tintori c. 1960. Photo: Opera di Santa Croce, Archivio Storico and Fondo Edifici di Culto

Despite improved understanding of Titian’s life and art, 19th-century responses to his painting maintained long-established tropes. Much effort was expended trying to discover the ‘secret’ of Titian’s technique, especially his multiple layers of glazing, and this intense concern for tone manifested in anxiety over varnishes. Pietro Edwards, director of the Restoration of the Public Pictures of Venice for many years from 1778 and a crucial figure in the history of conservation, popularised the use of mastic as an easily removable varnish and demanded that retouching be restricted to areas of paint loss. Hayes demonstrates that, when it came to the restoration of Titian’s Assunta in 1817, these conservative principles were not strictly adhered to. The sky and the ‘glory’ were broadly varnished and glazed, altering spatial relations, reducing contrasts and rendering Heaven and Earth more unified. The changes Edwards oversaw (some still present on the painting’s surface today) shaped later responses to the work and to Titian himself.

Charles Eastlake’s directorship of the National Gallery (1855–65) receives a particularly thorough and revealing treatment, recording his meticulous instructions and his desire for precise aesthetic results. Controversies over the cleaning of pictures in the 1840s meant that Eastlake, working closely with the gallery’s keeper Ralph Nicholson Wornum, was secretive about restorations and limited them to new acquisitions. Though Eastlake has been widely believed to have had paintings restored in Italy, engaging Giuseppe Molteni in Milan, most treatments were in fact done in London. Once a painting was hung in the gallery its appearance could not change, and Eastlake was especially concerned to achieve an ideal tone and patina, conforming to public expectations. Although cautious, he was willing to correct what he perceived as faults in paintings: we see a subtle censoring in Bronzino’s An Allegory with Venus and Cupid and discover little ‘improvements’ made to a Filippino Lippi altarpiece. In all Eastlake’s instructions, Hayes demonstrates the director’s fidelity to a particular notion of the Renaissance.

Circumspection was not a quality one would attribute to Wilhelm von Bode, the director of the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, or to his in-house conservator Alois Hauser Jr, who ‘secured and remade paintings’ illustrating what Hayes describes as Bode’s ‘idiosyncratic’ version of the Renaissance. Most notoriously, in 1893–94, through a ‘terrifying’ procedure, Hauser split the wings of Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece so that both sides of the panels could be displayed simultaneously. In 1885 English buyers had rejected Sebastiano del Piombo’s Portrait of a Young Woman because of its ruined condition, which led to it being bought by Bode and receiving ‘aesthetic enhancement’ from Hauser. A long discussion of Andrea del Sarto’s Madonna and Child Enthroned (likely destroyed in 1945), illustrated with photographs documenting the extent of Hauser’s repairs, shows that while his additions may seem excessive by current standards, they were based on close study of original works. Bode’s and Hauser’s concern with good condition, with uniformity of effect, may also explain why in the early 20th century these restorations could be described as ‘forgeries’, which ‘damaged the reputation of the Berlin Museums’.

Many 19th-century layers have now been removed from Renaissance works, but others remain, determining what we see. Hayes’ book is a reminder that the painting on the wall is not static but has changed – sometimes dramatically – through time and embodies that history.

The Renaissance Restored: Paintings Conservation and the Birth of Modern Art History in Nineteenth-Century Europe by Matthew Hayes is published by Getty Publications.

From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home