Letters, newspaper clippings, photographs and sketches make up the majority of the material exhibited in the Whitechapel Gallery’s ‘Sculptors’ Papers’ (until 22 February 2015). Drawing on the Henry Moore Institute’s rich archive of sculptors’ papers in Leeds, the exhibition illuminates the stories behind some of London’s most radical public sculptures, commissioned from the early 20th century onwards. Focusing on the journey that works take from conception to installation, the exhibition offers an insight into the hard graft involved in gaining consent for public sculpture, and the often-polarised reactions it receives.

Photograph of Jacob Epstein in studio with plaster model of ‘Dancing Girl’; commission for the British Medical Association Building, Strand and Agar Street, London (c. 1907) © Tate Enterprises Courtesy Leeds Museums & Galleries (Henry Moore Institute Archive)

Contemporary artist Neal White opens the show with his The Third Campaign (2004–05), a crusade to reinstate the defaced Jacob Epstein British Medical Association sculptures (1908–37) that decorated their headquarters on The Strand. Commissioned to represent the seven ages of man, they consisted of 18 eight-foot sculptures of nude figures with chunky thighs, straight roman noses and pronounced musculature. When they were installed, they received a split response from the public; much of the Edwardian audience deemed them ‘indecent’, while others hailed them masterpieces of modernism. Finally, in 1937, at the command of the Rhodesian Government following their acquisition of the building, they were partly chiseled away, leaving only torsos, limbs and spectral faces.

White’s campaign involved writing to prominent art world figures including Brian Sewell and Penelope Curtis, and a protest on The Strand where he wore luminous placards bearing the sculptures’ names. Reinvigorating Epstein’s own campaign to protect the figures, White’s work acts as an investigation charting attitudes to public works.

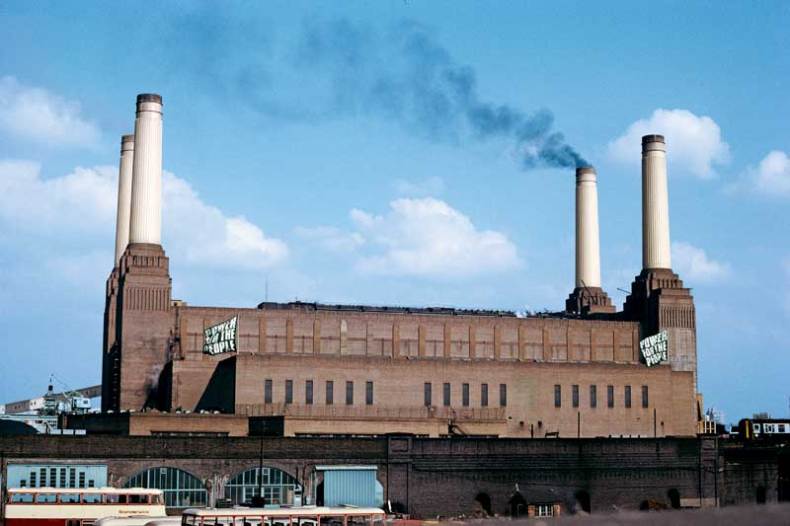

Rose Finn-Kelcey’s sculptural project stood out. Power for the People (1972) saw four black flags, each emblazoned with large silver letters spelling out the title, installed on the four corners of the Battersea Power Station. Accompanying documentation charts the idea’s mutation from Finn-Kelcey’s original proposal for ‘30 flagpoles sited on selected buildings along the Thames’ to its realisation. Despite a number of setbacks, it is interesting to note how the final work still embodies the philosophy she wished to construe – ‘a public art form which is neither pompous, interfering nor condescending’.

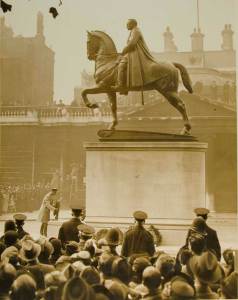

King George V laying a wreath at the monument to ‘Field Marshal Earl Haig, Commander-in-Chief of the British Armies in France 1915-1918’ by Alfred Hardiman, Armistice Day (1937) © The Hardiman Estate. Courtesy Leeds Museums & Galleries (Henry Moore Institute Archive

Other works elicited violent responses. Lawrence Bradshaw’s Karl Marx Memorial (1956), commissioned by the British Communist Party to decorate Marx’s grave in Highgate Cemetery, north London, became a site for political pilgrimage, vandalism and even bomb attacks. An intimidating, squat bust of the politician – plus numerous newspaper clippings – document its tempestuous past. Likewise, the equestrian monument of World War I Field Marshal Douglas Haig (1928) by Alfred Frank Hardiman aroused one of the greatest responses ever to a public monument. Showing the Earl on a horse, it was deemed old-fashioned because modern warfare was mechanical. His widow, Lady Haig commented it was ‘too theatrical’ and that she ‘hoped it would be smashed to smithereens’.

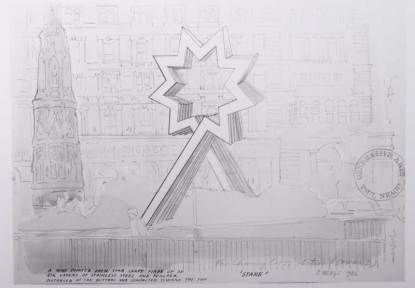

There were also failures. Romanian sculptor Paul Negu’s powerful Starhead (1968) was a nine-pointed Perspex and steel star sculpture, commissioned by the Westminster City Council for Charing Cross. Despite winning a competition to be installed on the site, it was met with intense opposition, with the Charing Cross Hotel referring to the design as an ‘eyesore’: it was finally scrapped due to insufficient funding. The Temple of Universal Ethics (c. 1939) also never progressed past the drawing board. Designed by Croatian artist Oscar Nemon, it was a utopian proposal for a political and intellectual hub and institute for international relations. A curving, soaring architectural model orientated towards the sky, the grand design never came to fruition.

Through showing the steps involved in creating, planning, funding and erecting public sculpture, the exhibit illustrates the difficulties involved. Because of their existence in ‘common’ and ‘public’ space, the reactions elicited are varied, tempestuous and sometimes violent. Public sculpture enriches and enlivens urban landscapes, whilst also engaging the general public. Using a variety of examples, the exhibition displays the range of public sculpture existing in London, whilst showing how it acts as a democratic soundboard for the zeitgeist.

‘Sculptors’ Papers from the Henry Moore Institute Archive’ is at the Whitechapel Gallery until 12 April 2015.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home