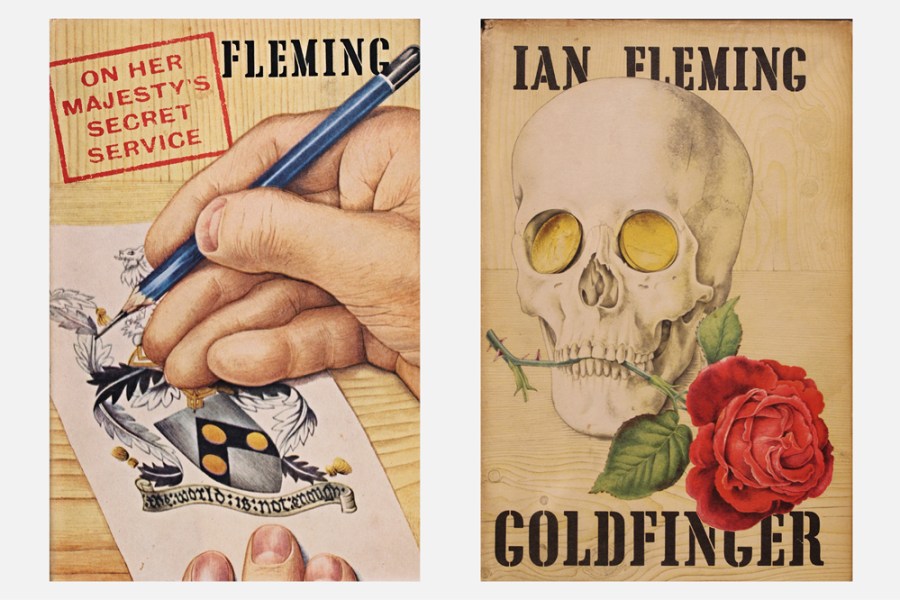

In April 1956, at the suggestion of his friend Francis Bacon, Richard Chopping took the society hostess Ann Fleming to see some of his trompe l’oeil paintings, which were then on show at the Arthur Jeffress Gallery in Mayfair. Impressed by these pictures, Fleming invited the artist to meet her husband, Ian, who was looking for someone to provide dust-jacket illustrations for his James Bond novels. Chopping was immediately offered the job, and his striking designs remain the work for which he is best known and are, for many collectors, the reason the novels are particularly prized.

As this small but imaginatively curated exhibition demonstrates, there was a great deal more to Chopping than James Bond. Nevertheless, the highly detailed, finely executed and often macabre paintings he produced for Fleming are characteristic of his work as a whole. Born in Essex in 1917, Chopping moved to London at the age of 18 with little idea of what he wanted to do, but soon got a job on the magazine Decorations of the Modern Home. He then took a course in stage design, but his life took a different direction when he was picked up at the Café Royal by Denis Wirth-Miller, then an aspiring artist, with whom he embarked on a lifelong, though notoriously tempestuous, relationship. Wirth-Miller suggested that they should both enrol at Cedric Morris’s East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing, where they were befriended by their fellow student Lucian Freud, to whose early paintings Chopping’s work bears some resemblance. Like many others, they would soon fall out with Freud, but more crucially they also met the author and illustrator Kathleen Hale. She would become a loyal friend and was so impressed by a children’s book about a giraffe that Chopping had written and illustrated that she introduced the young artist to Noel Carrington, the publisher at Country Life of her own Orlando books. Although ‘Gwladys, the All-British Giraffe’ was never published, Carrington would go on to found the Puffin imprint and commission Chopping’s first illustrated book, Butterflies in Britain. Published in 1943, the book demonstrated Chopping’s ability to produce meticulously detailed and carefully composed lithograph illustrations that were works of art in their own right.

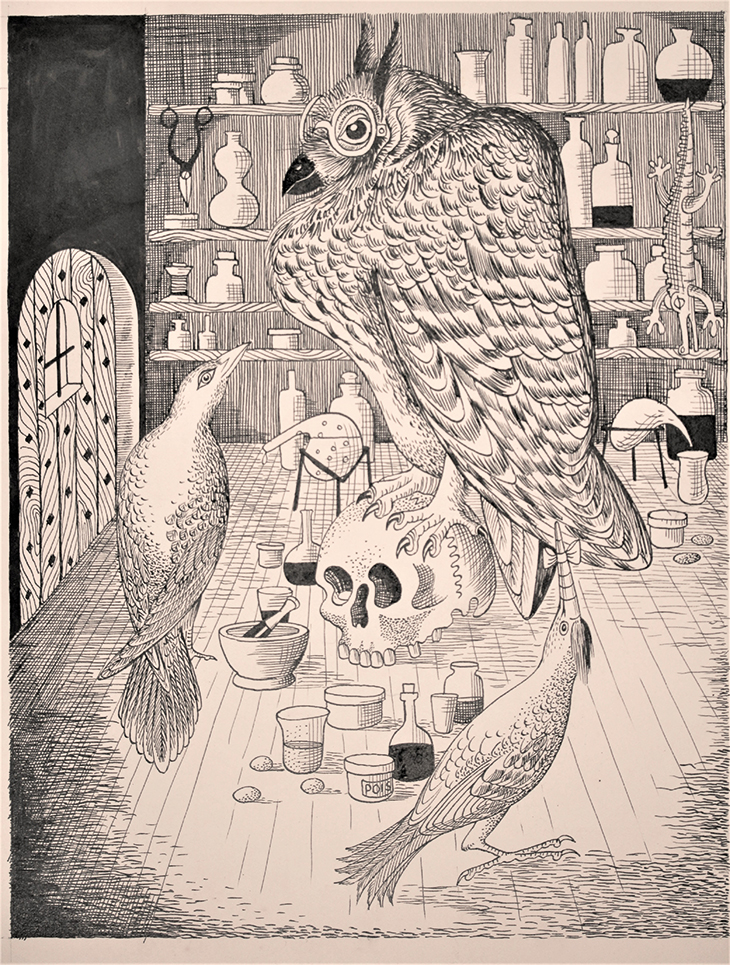

Large owl from ‘The Woodpecker in the Gale’ (in Mr Postlethwaite’s Reindeer) (1945), Richard Chopping. Private collection. © the Estate of Richard Chopping

Freud recalled that Wirth-Miller was at this period ‘doing Weimar Republic paintings’, and two of Chopping’s early paintings of family groups in the exhibition also show the influence of George Grosz and Otto Dix. Chopping soon moved away from this style of painting, but drew similarly grotesque human figures for his children’s books. These reflect his written descriptions of the characters: for example, a duchess in Mister Postlethwaite’s Reindeer (1945) has ‘an ageing face like roses sprinkled with vinegar’. This startling image is characteristic of Chopping’s lively visual imagination, and some of his portraits from the 1960s are equally unsettling. They are beautifully painted, but the features – eyes, eyebrows, nose and mouth – float disconcertingly on a flat plane, as if the face had been lifted intact from the skull.

Allen Lane commissioned Chopping to provide illustrations for a hugely ambitious 22-volume book for Penguin on British wild flowers with a text by Frances Partridge. Artist and writer became close friends and spent five years hunting for specimens to paint and write about; but in 1949, just as the first volume was about to go to press, they were told that Penguin’s accountants had decided the project would bankrupt the company and was therefore being cancelled. The paintings on display here, a mere handful of the 110 or so Chopping completed, suggest that the abandoned book would have been a milestone in natural-history publishing.

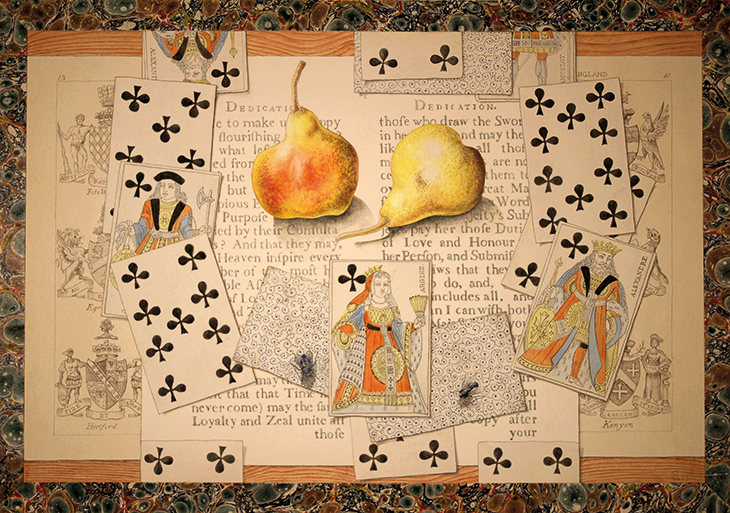

It was the skills he had honed in depicting butterflies and plants that led Chopping to try his hand at trompe l’oeil pictures, in which he determined to combine ‘the exactitude of a scientific observer [with] the sensibility of a painter’. The critical and commercial success of these paintings meant that Chopping now had a career as an artist as well as an illustrator. The exhibition includes several beautiful examples of this exacting work, notably a picture of two globe artichokes artfully arranged on overlapping pages torn from an old botanical volume and laid on a wooden plank.

Fruit and Playing Cards Trompe l’Oeil (1953), Richard Chopping. Private collection. © The estate of Richard Chopping

This painting also features two houseflies, insects that not only appear frequently in Chopping’s paintings and drawings but also swarm over the jackets of Fleming’s The Man with the Golden Gun (1965) and Octopussy and The Living Daylights (1966) and feature on a Saturday Book annual of 1955 and the two novels Chopping published in the 1960s, the first of which was even titled The Fly (1965). Their presence clearly nods to the 17th-century tradition of vanitas paintings, and a preoccupation with death and decay carries over into Chopping’s fiction. The horrifying dust-jacket image for his first novel, shown here in several stages of development, depicts a fly in extreme close-up settled on the edge of a human eye widened in death. The novel itself was variously described in the press as ‘extremely cool and nasty’ and ‘the most unpleasant book of the year’, but it could more justly be said that in both his artworks and fiction Chopping’s vision of the world was direct and unflinching. The keen, almost obsessive attention to physical detail Chopping displays in his paintings is apparent in his second novel, The Ring (1967). Its opening paragraphs might almost be describing one of his own pictures, a kind of verbal still life that includes a long, minutely observed and quite extraordinary depiction of three carnations in a tumbler.

At Salisbury, a fascinating insight into Chopping’s working methods is provided by displays of props, photographs, cigarette cards, scribbled notes and other source material for his various projects – notably a wooden box of dead insects. Photographs of the human skull Chopping had been loaned to ‘model’ for the dust jacket of Goldfinger (1959) are shown alongside several stages in the jacket’s development, from initial sketches to finished product. Such attention to working methods seems appropriate, and is characteristic of an exhibition that, despite its title, allows Chopping to emerge from the long shadow cast by Bond and be appreciated as a remarkable and highly original artist in his own right.

‘Richard Chopping: The Original Bond Artist’ is at the Salisbury Museum, Salisbury, until 3 October.

From the September 2021 issue of Apollo; preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home