Exhibitions about exhibitions; exhibitions about curators; exhibitions about exhibition spaces – retrospectives are no longer just for artists. ‘Sandra Drew: From the Kitchen Table’ at the newly renamed Southwark Park Galleries (formerly CGP London) is one of several recent examples, including ‘Signals: If you Like I Shall Grow’, at Thomas Dane gallery in London (2018); ‘Just Above Midtown: 1974 to the Present’ at MoMA in New York (recently announced for 2022) and ‘For Your Infotainment: Hudson and Features Inc’ at Frieze New York (2018). What does it mean to employ an exhibition format to think through the legacy of a curator or a gallerist?

‘From the Kitchen Table’ traces the networks of influence of the pioneering Australian curator Sandra Drew. Working from her kitchen table, Drew produced a series of exhibitions in unconventional sites such as crypts, empty shops, and disused or derelict public spaces across Canterbury in the 1980s. Working primarily with emerging artists – many of whom, this exhibition reveals, were female – Drew championed approaches, such as the use of new media, that were out of step with traditional discourses of sculpture at the time. This, along with her radical approach to site and context that prefigured commissioning models such as Artangel and the Folkestone Triennial, has since become more familiar. Touring from its first Canterbury location, the exhibition in London straddles Southwark Park Galleries’ two venues: a characterfully derelict chapel with vaunted ceilings and a more traditional white cube space, the architecture of which is perhaps not the best reflection of Drew’s curatorial legacy of site-specificity.

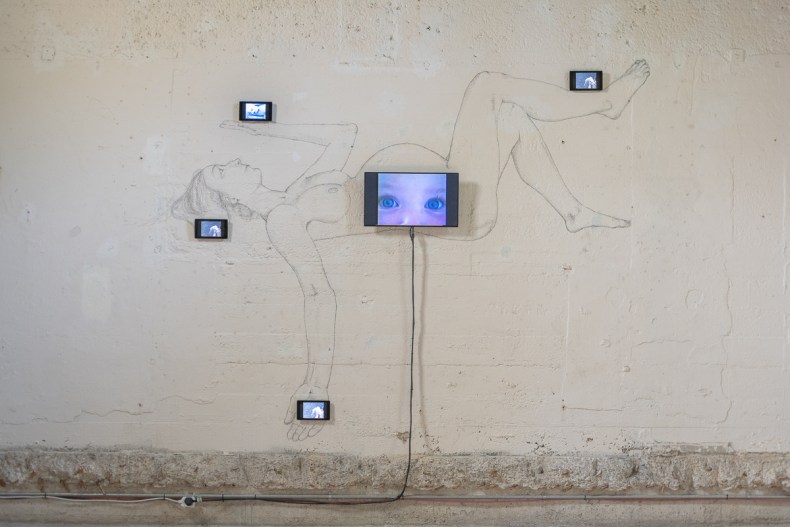

Hannah’s Song (1986–2019), Katharine Meynell. Photo: Damian Griffiths. Courtesy Southwark Park Galleries

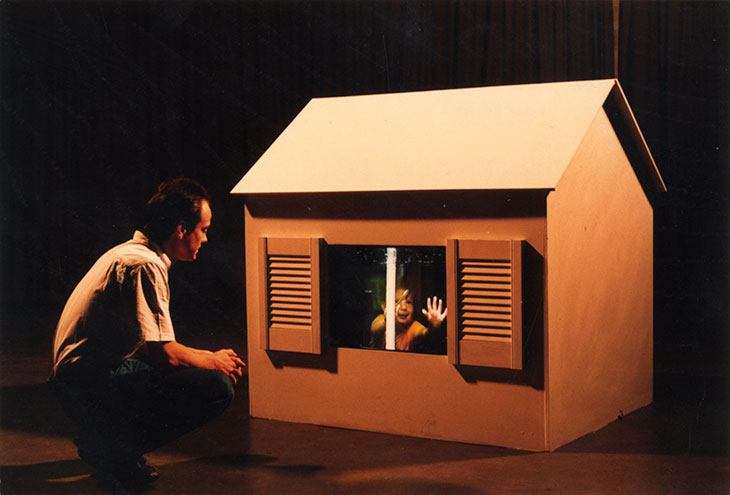

There are some archival photographs but the exhibition is mostly made up of the artworks Drew exhibited, recreated using a mixture of original and updated technology. Alongside now rightly celebrated artists such as Phyllida Barlow and Rose Finn-Kelcey, ‘From The Kitchen Table’ is full of discoveries, not least Hannah’s Song (1986) by Katharine Meynell – a large-scale, fragile drawing of a female figure on the chapel’s peeling plaster walls, with small screens dotting the figure’s body. Each of these screens displays flickering ultrasound imagery, and the accompanying audio of Meynell’s young daughter singing evokes the artist’s disorientation in the post-partum period. Similar themes are present in Catherine Elwes’s First House (1986), a dollhouse-like multimedia installation reflecting on her struggle to balance a feminist art practice with motherhood. These works were both part of the same exhibition, Drew’s ‘3rd Generation: Women Sculptors Today’ (1986), but here they are split across the two venues. A certain curatorial informality eschews explicit links between works, leaving conversations to open up as they might well have around Drew’s kitchen table. While the exhibition cannot replicate Drew’s strategy of placing art in unusual contexts, it stays true to the intimacy of her work and the networks that her model built.

First House (1986), Catherine Elwes. Courtesy the artist

Exhibitions like this one increasingly recognise the place of the curator or gallerist within art history, and the rise of curatorial authorship. They also practice a social kind of art history, providing a model of thinking through artistic networks that, with its less linear approach, has great potential for widening the canon. As in the case of ‘From The Kitchen Table’, they can also highlight the stories of what might have been: we rightly encounter each of the participating artists on the same level, despite wildly divergent careers since. What made some of these artists’ careers take off and some remain in relative obscurity?

As museums like MoMA, small non-profits like Southwark Park Galleries, commercial spaces and even art fairs turn – somewhat unsurprisingly – to their own histories, the question arises: which artists, and which curators, might be next in line for rediscovery? The increase in attention paid to previously overlooked spheres of activity, such as Sandra Drew’s projects or Linda Goode Bryant’s gallery Just Above Midtown, a key platform for African-American artists in New York in the 1970s and ’80s, is welcome. It remains to be seen what the market implications for this are. Gallerists already manage historic artist estates, so could the concept of a curator’s estate really be so far off?

‘From the Kitchen Table: Drew Gallery Projects 1984–90’ is at Southwark Park Galleries, London, until 30 June.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home