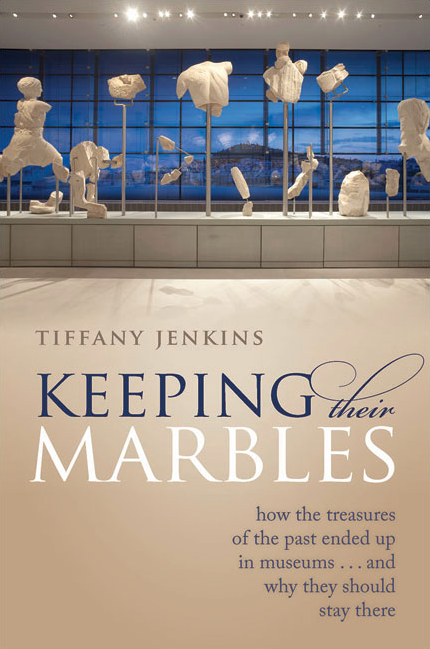

The argument over the rightful ownership of the Elgin Marbles has been a running sore ever since the British Museum acquired them in 1816. The Greek government has more pressing problems at present, but there is no doubt that Greek museologists, and their British supporters, will return to the fray. The subtitle of Tiffany Jenkins’s book makes it clear where she stands, but although ‘the marbles’ form part of her case, the book has a larger purpose: to disperse ‘the negative cloud surrounding museum institutions’ as a result of the politicisation of culture. The ever louder claims for the repatriation of objects is, in her view, a sign of this deeper malaise.

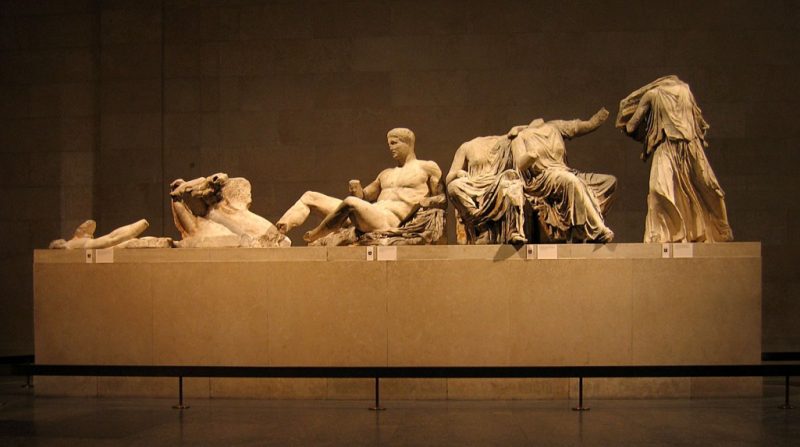

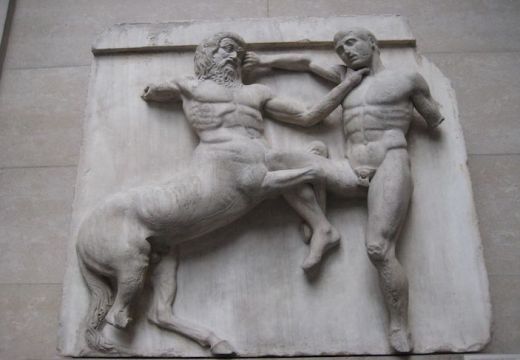

The first half of Jenkins’s argument is a rapid account of the formation of key Western museum collections, from the voyages of Captain Cook to the international conventions on cultural property that apply today. Although Jenkins gives a horrifying picture of the damage Lord Elgin did to the structures from which he prised his marbles, she writes that ‘Elgin neither looted nor stole the sculptures’. When the insolvent and syphilitic Elgin offered them to the British government, and the matter was debated in Parliament, some thought the money better spent on sick sailors; others produced a Creative Industries argument – the acquisition was ‘for the encouragement of arts, the increase of manufactures’.

The first half of Jenkins’s argument is a rapid account of the formation of key Western museum collections, from the voyages of Captain Cook to the international conventions on cultural property that apply today. Although Jenkins gives a horrifying picture of the damage Lord Elgin did to the structures from which he prised his marbles, she writes that ‘Elgin neither looted nor stole the sculptures’. When the insolvent and syphilitic Elgin offered them to the British government, and the matter was debated in Parliament, some thought the money better spent on sick sailors; others produced a Creative Industries argument – the acquisition was ‘for the encouragement of arts, the increase of manufactures’.

Jenkins then turns to more controversial cases: the Benin bronzes sold to pay for the punitive expedition of 1897, and the destruction of the Chinese Summer Palace by an Anglo-French force in 1860. She notes that while the bronzes are the subject of repatriation claims by the Nigerian government, so far the Chinese authorities, while anxious to trace the soldiers’ loot, have not begun proceedings. The British Museum may not have been designed as ‘a museum of conquest’, but the Rosetta Stone, discovered by the French and taken off them by the British, ended up there. Under Napoleon, the Louvre merited such a designation, but Jenkins argues that his activities were ‘legal seizure’. (In spite of his defeat, 45 per cent of what his armies took has not been returned.)

The German and Russian depredations during the Second World War, however, are only briefly mentioned. There is no discussion of the UK government’s Spoliation Advisory Panel or the Holocaust (Return of Cultural Property) Act 2009. Do the sales forced on Jewish owners constitute ‘legal seizure’? In Part II Jenkins turns to what she sees as the real reason for the spread of repatriation claims: the ‘new museology’ that argues that museums function in the interests of the powerful, that their claims to represent objective truth are ideologically suspect, and that the stories they now tell of oppression and expropriation are actually harmful. But culture as a whole, not just museums, is being perverted by politics; politics that are clearly not Jenkins’. Although she does later accuse some museum professionals of ideological perversity, the sources of this corruption are cultural theorists such as Stuart Hall and Tony Bennett, whereas she can cite in her support a powerful practitioner, James Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust.

The fundamental objection is to the use of museums for instrumental purposes. The Victorians may have hoped museums would improve people’s lives, but they believed in ‘cultural authority, expertise, truth, and perfection’. While one may agree that museums have recently become instruments of urban regeneration, it is difficult to imagine a time when museums did not have an instrumental purpose, going back to the foundation of the British Museum as the first ever ‘British’ institution. Jenkins’ objection, however, is to the ‘therapeutic measures, such as the recognition of historic ills’, which treat repatriation as reparation.

This is the sort of argument set out by the sociologist Frank Furedi in his Therapy Culture: Cultivating Vulnerability in an Uncertain Age (2003). Jenkins cites another member of this school of thought, London’s deputy mayor Munira Mirza, from her The Politics of Culture: The Case for Universalism (2011). The case for universalism is that cultural objects (such as the Elgin marbles) can transcend their historical context and exist on a higher plane, where the contemplation of their aesthetic qualities gives them a universal authority. Yet many of the arguments that Jenkins puts forward against repatriation are themselves relativist: ‘the elite’s promotion of culture was self-interested and partial’; ‘no culture, or people, has ever been fixed throughout history’.

Nonetheless, Jenkins uses the universalist case to criticise in particular what she calls ‘identity museums’, such as the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, ‘memorial museums’, which address the Holocaust or slavery, and the practice of returning human remains, which she discusses in a chapter called ‘Burying Knowledge’. This latter practice she sees as a sign of professional guilt, rather than a response to a genuine demand from formerly colonised peoples.

Jenkins sees the collapse of grand museological narratives as the sign of a ‘post-ideological age’, but this book is hardly ideology-free. Concluding with the explosion of museum building in the Gulf and China, she writes that ‘money has replaced might’. Yet these museums are a physical manifestation of the geopolitical forces that once brought the marbles to London. It seems inconceivable at present, but Greece may yet get them back.

Keeping Their Marbles: How the Treasures of the Past Ended Up in Museums…and Why They Should Stay There, by Tiffany Jenkins (Oxford University Press)

From the April issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home