Curator Peter Carpreau talks to Sophie Barling about the restoration of St Peter’s Church in Leuven, home to two masterpieces by Dieric Bouts, one of which can still be seen in the chapel for which it was originally made.

Originally built in 986, St Peter’s is the oldest church in Leuven, but its current gothic incarnation dates to the 15th century. It’s been restored many times since, notably after fire damage in the two world wars. What prompted this latest restoration?

Air pollution. The church was constructed with a very soft kind of sandstone, which worked as a sponge for acid rain and car fumes. It was completely darkened. That work has been going on for 20 years; but more recently it gave us the idea to rethink the interior of the church. Previously the church was divided into two parts – the choir was a museum area and the rest of the church used for worship. But given that all the artworks in the church are religious, and to be experienced in a religious surrounding with all the religious aspects, the mass, the candles etc., we felt we should combine those two functions. We then identified 12 objects from the church, highlights that each tell a different story.

Including the tomb of Henry I, first duke of Brabant [c. 1165–1235]?

Yes, it’s the oldest surviving tomb of its kind in the Low Countries. He was a very important political figure in the medieval period. But the fun thing was that the tomb was in fact in the middle of the church, and we moved it back into its earlier position – I don’t say original position, because it was made for a church that is no longer extant. We moved the entire tomb and noted that within it was a small zinc box in which we expected to find the skeleton of Henry I. But it was Henry II, his son. We had also heard that there were other zinc coffins that were walled up in the Romanesque crypt, so we found three other boxes, and it turned out to be a large part of the Brabant family. That was one of the more remarkable discoveries we made.

The tomb of Henry I, first duke of Brabant (c. 1165–1235). Photo courtesy M Leuven

The church is also home to The Last Supper triptych by Dieric Bouts, commissioned for the building by the Fraternity of the Blessed Sacrament and completed in 1468. Why is this such an important painting?

It’s one of the masterworks of 15th-century Flemish painting, and is still to be seen in its original chapel, which is quite extraordinary. It is well documented: we have several contracts between the brotherhood and Dieric Bouts, concerning the painting commission, the payments, and the help he received from the [recently founded] University of Leuven to think out the iconography. It’s the first monumental depiction of the Last Supper, and it’s also one of the earliest examples of really thought-through mathematical perspective.

This is a painting that was made in the light of ideas about the democratisation of religion. At the end of the 14th century you had the Devotio Moderna instigated in the Netherlands, which was in effect a religious movement to reform the church; it held that even if you weren’t a man of the cloth, you could still live a very religious, spiritual life. And that’s why those religious brotherhoods were born: they were laymen acting as religious figures. It was in this context that the brotherhood of Leuven, which placed great emphasis on the Eucharist, asked Bouts to create an image of the Holy Mass.

The triptych has had a turbulent history, even before the Nazis confiscated its central panel in 1942…

That’s right. In the 18th and 19th centuries people lost interest in Flemish paintings of the 15th century, and started to sell these works; in Leuven they sold the side panels, and kept the central panel. They were sold to an antiques dealer in Brussels and then they went somewhere in Germany. After the Treaty of Versailles, the panels were given back to Belgium, together with the Ghent Altarpiece, as reparation for the war. So a peculiar result is that the central panel is still owned by the city of Leuven, while the outer panels are owned by the Belgian state.

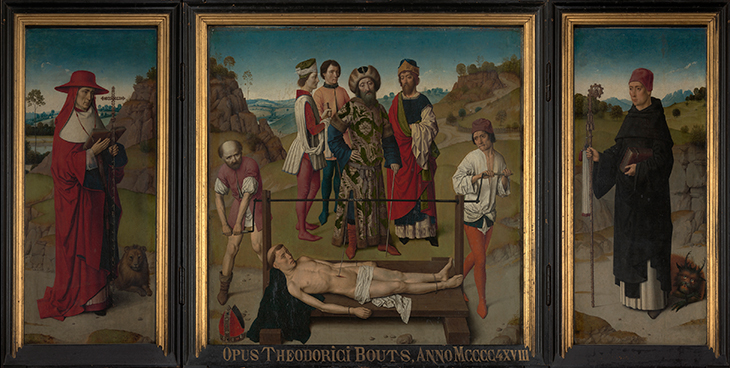

The Last Supper was restored in the late 1990s. You’ve just had conservation work done to the other Bouts work commissioned for the church, The Martyrdom of St Erasmus (1465). Has anything been discovered about it?

I’m still waiting for the restorer’s report, but he did show me a few discoveries, mostly concerning colour that has changed over time. We’re going to use all the technical data gained from that restoration to do research on other paintings by Bouts; we recently acquired a small panel painting [from the workshop of Dieric Bouts], a Man of Sorrows, for the Museum Leuven. We’re planning a large Bouts show in 2023, combining a lot of his works in Leuven.

The Martyrdom of St Erasmus (c. 1458), Dieric Bouts. St Peter’s Church, Leuven. Photo courtesy M Leuven

What are some of the other highlights you’ve picked out?

Along with the two Bouts paintings, there was a third object in the church commissioned by the brotherhood: a huge tabernacle created just next to the Bouts. Another unusual object is the architectural model [from 1524] for the west towers of the church, which in fact were never built. At the time the church was intended to be the highest in the Low Countries – or even north of the Alps. We have the drawings in the museum and the model standing in the church that was created by the architect at the time [Joost Massys].

We’re also focusing on other local stories, including the chapel of the beer brewers – you can’t miss that in Belgium – where we’ll tell the story of Leuven as a centre for beer making. And we’re returning the Edelheere Triptych – the first contemporary copy of Rogier van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross [Prado] – to the chapel of the Edelheere family, who commissioned it. That’s something we wanted to do, to try to bring all the objects that we knew were commissioned for the church back to the church, and to remove objects that had nothing to do with it.

The church of St Peter’s was still being completed when Bouts was painting The Last Supper. What do the church and its contents tell us about that historical moment in Leuven?

It’s an artistic overview of one of the most productive moments of the city. At the time, the town hall was being built [something Bouts depicts through a window in The Last Supper, across the Grote Markt from the church]; Leuven was in direct competition with Brussels, so they were trying to outdo Brussels for beauty. That city was a political competitor because Henry I had made Leuven the capital of the duchy of Brabant, but one of his successors moved the capital to Brussels; that didn’t go down well here in Leuven, so the inhabitants tried to regain their status. And they did that by commissioning extraordinary artworks and extraordinary buildings.

The Triumphal Cross (c. 1495) by Jan Borman, installed in St Peter’s Church in Leuven. Photo: courtesy M Leuven

The redisplay at St Peter’s Church, part of Museum Leuven, opens on 7 March.

From the January 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home