The painter Stanley Spencer suffered from a benign kind of graphomania: he wrote, and wrote, and wrote. Almost everything he wrote – whether in notebooks, diaries, or letters (especially to his wife Hilda) – was about himself. He thought of it as a kind of autobiography. If so, it was an autobiography that could never be published: not only was it vast and baggy and generically unstable, repetition was deliberately of its essence, as was an airy disregard for chronology. He wanted his writing to have the ‘tempo of walkers out blackberry-picking’. And he could not bear to leave anything out. ‘The task of editing Spencer’s autobiographical manuscripts would have been Herculean,’ wrote Adrian Glew in his introduction to the 2001 anthology of the artist’s writings from the Tate Archive. And yet this Herculean task has now been undertaken by the painter’s grandson, John Spencer, who has drawn on family archives as well as the many papers in the Tate and elsewhere.

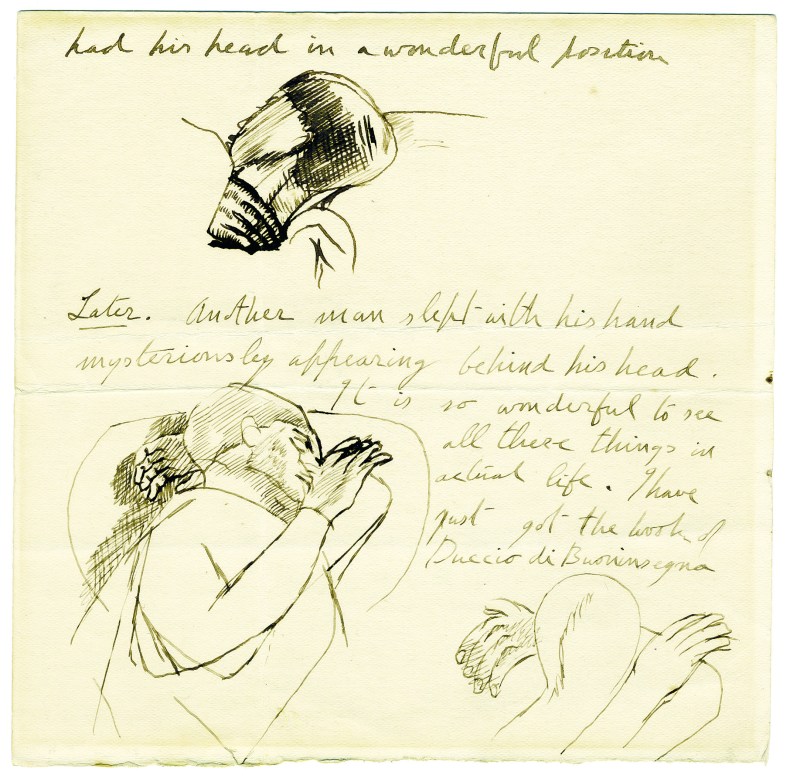

Three volumes have been planned, of which Looking to Heaven is the first. It covers the period of Spencer’s life up to the end of the First World War, including his childhood in Cookham, his time at the Slade and early career as an artist, and then his war service as a hospital orderly in Bristol and then on active service in Macedonia. It’s a period that includes some of Spencer’s richest years as an artist, resulting in the early visionary works such as John Donne Arriving in Heaven (1911), Joachim among the Shepherds (1913) and Zacharias and Elizabeth (1913–14). It also encompasses those years in the First World War in which Spencer had the experiences that would later find visual form in the Sandham Memorial Chapel at Burghclere. One of the most rewarding things about reading Spencer’s letters and notebooks from this period is to come across descriptions (and sometimes drawings) of things that might later surface at Burghclere or in other war works, like the diagram of the components of a kit inspection at Tweseldown Camp, or the lovely drawing of a recruit asleep ‘with his hand mysteriously appearing behind his head’.

Given how complex the editorial process behind this volume must have been, it is described very briefly, in just two pages. ‘Our initial aim was to include everything,’ we are told – an alarming prospect – though it soon became clear that there were often several versions of the same bit of writing. In these instances only one version – the one in the family archive – has been chosen. Whether everything else has been included is not clear. It is very useful to have so many letters reproduced, apparently in their entirety (although not always accurately, as comparisons with the few facsimiles reproduced shows). But it is one of the oddities of the book that only a few of the other pieces of writing that comprise the whole are given a date or context. There is no list of sources. In many cases we don’t know whether an autobiographical fragment was written soon after the events it describes or many years later. This is mainly a problem for the scholar rather than the general reader, but it also elides something important, because Spencer used writing as a way of remembering things at particular times in his life. The Cookham he remembered after the break-up of his marriage, for instance, was a different Cookham to the one he remembered when he was away at war; and so on.

Letter from Stanley Spencer (1891–1959) to Desmond Chute, written in Tweseldon Camp in Surrey, summer 2016. Images courtesy Unicorn Press; © Estate of Stanley Spencer

Certainly it will be interesting to see what will be done editorially in the later volumes when Spencer interminably revisited times and places, especially those connected with his first marriage in lengthy letters to Hilda to assuage his loneliness. If everything is to be included then these volumes will have to be hefty tomes indeed. Yet one positive element of John Spencer’s editorialising is the potential de-bowdlerising of the artist’s scribblings; the Tate anthology felt somewhat sanitised. The word ‘fucking’ for instance appears in the first few pages of Looking to Heaven in a piece of writing from 1935 (perhaps he’d been reading the outlawed Lady Chatterley’s Lover in Patricia Preece’s Cookham cottage). And as though to indicate that the editor has not made even minor cuts, there are plenty of references to ulcers, indigestion and other ailments.

In a way the oddness of Looking to Heaven is of a piece with Spencer’s own oddities, making criticism seem churlish. Editorial questions aside, the fact is that Spencer could be a terrific writer, although in books and articles about his painting it tends to be the same few quotations that are cited (something that will surely be remedied by the appearance of these three volumes).

His particular way of viewing the world, so evident in his paintings, is equally (but differently) evident in his writing. To take just one example, in a piece of writing describing the garden of his childhood home in Cookham, Spencer describes a walnut tree that grew there, so tall that its uppermost leaves had no idea where its trunk or roots were. The tree, he writes, ‘lived a polyamorous life’ (as Spencer himself hoped to at the time of writing), casting its shade over neighbouring gardens, some of them unknown, as well as the Spencer’s family garden. When he saw ostlers near his house cracking walnuts from this tree in the palm of their hands, he found it hard to believe that they were the same as those that his father would take out of his pocket and place on the dining room sideboard. The boy’s absorption in his immediate environment, recognising no real difference between child and tree, has been preserved, as has a weird sense of a thing – in this case a walnut – being different depending on where it appears.

Later Spencer describes an artistic breakthrough when he drew a dead thrush that had, he thought, been in all sorts of ‘ungetatable places’ in this tree. It was the beginning – or a beginning – of not just feeling but conveying that sense of the indivisibility of being and place that was such an important part of his work.

Stanley Spencer: Looking to Heaven by John Spencer (ed.) is published by Unicorn Press

From the April issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home