‘Hyperréalisme’ at the Musée Maillol in Paris, presents around 40 contemporary sculptures alongside paintings and sculptures by Aristide Maillol from the museum’s permanent collection. In an attempt to define the hyperreal, the exhibition catalogues a mode of working, beginning in the 1960s with the development of modelling technology such as silicone, that seeks to replicate human bodies exactly, warts and all. The attention of hyperreal artists to the nuances of skin tones, age spots, bulging veins, and body hair would likely have been anathema to Maillol, working in the late 19th and early 20th century; he claimed that ‘the particular does not interest me’ as he transformed individual women into his ideal sculptural volumes. But the resonance of hyperreality today – in an era when we seem to have lost touch with the real, as photo filters reign and the arrival of the metaverse looms – is clear. Seen in conjunction with another recent exhibition in Paris – ‘Things: A History of Still Life’, at the Louvre – the show raises intriguing questions about things that last and things that don’t.

At the Musée Maillol, a flesh-toned nude by John DeAndrea is outnumbered by a group of allegorical Maillol bronzes; the comparison serves neither very well. Instead, the most potent moments in the exhibition are those when the visitor is duped – an effect augmented by the exhibit’s dim lighting, dark walls and small spaces. Turning a corner to find a Daniel Firman sculpture facing the wall, one would be forgiven for waiting politely for it to move on, so that other visitors can see what it is looking at. The result can leave one feeling foolish, or something more.

Woman and Child (2010), Sam Jinks. Courtesy Musée Maillol, Paris

Woman and Child by Sam Jinks (2010) stands at 1.45m tall – or just under life-size. Its scale allows us peer intently at the elderly woman, whose skin, marked by time, appears more lifelike than the unnaturally still baby she cradles. We rarely come so close to a stranger, taking in her lined face, loose flesh, rounded nails and the tenderness with which she holds the pudgy, soft-skinned infant. It feels captivating, but also violating, to scrutinise her features so intently. There’s something repulsive about the experience – the result both of the viewer’s disturbing proximity to another body, even a lifeless one, and the sculpture’s embalmed quality. Perhaps it is a reminder of our own impending lifelessness. Roland Barthes found in the verisimilitude of the photograph a glimpse of death; hyperrealism extends the principle still further, going beyond the flatness of a photograph to preserve every minute wrinkle.

A Table of Desserts (1640), Jan Davidsz de Heem. Photo: © RMN Grand Palais, Musee-du-Louvre/Franck-Raux

This oblique reference to death was shared by the Louvre’s display of natures morte – its first presentation dedicated to the genre since 1952, and one that spans several thousand years. As with hyperrealism, part of the fun of the still life lies in being fooled by trompe l’oeil effects. The magic of the genre comes across most strongly in objects that awaken our desire to possess or consume them, such as a 2,000-year-old Roman mosaic fish or the enchanting spiral of an Indian ocean shell painted in the Netherlands during the 17th century. Still life makes us feel the futility of pleasure; we taste our own sin in our temptation by the image.

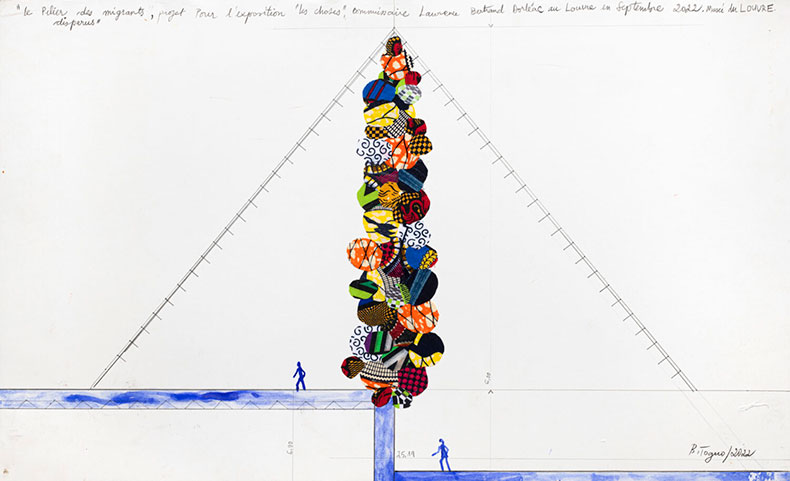

Still lifes of the 20th century are less realistic but no less pleasurable; in the exhibition, they included Meret Oppenheim’s sculpture Squirrel (1969), made with a beer stein, and a clip from Buster Keaton’s Scarecrow (1920) in which a dining table becomes a character study. A special commission for the Louvre pyramid, Le Pilier des migrants disparus (2022) by the Cameroonian artist Barthélémy Toguo, incorporated objects that have been both carried and left behind by migrants on their journeys. A stack of bulging packages wrapped in colourful African cloths, nearly 70 feet tall, Toguo’s work makes the still life’s reference to death a matter of practical and political, rather than just theoretical, concern.

Le Pilier des migrants disparus (2022), Barthélémy Toguo. Photo: Fabrice Gillbert; courtesy Bandjoun Station and Galerie Lelong & Co; © Galerie Lelong & Co

Perhaps above all, the pleasure of still life comes from knowing that something cannot last. Down the street from the Louvre, on the day of my visit, crowds were lining up to buy patissier Cédric Grolet’s trompe l’oeil creations at the Meurice, including a hyperrealistic €17 lemon, just as bright and glistening as those in Jan Davidsz de Heem’s La Desserte (1640). Cut open, the lemon revealed itself to be composed of soft mousse and tangy compote. To enjoy it requires dispelling its illusion, just as fully enjoying the painted lemon depends on seeing it as a painting and not a piece of fruit. Appearing hyperreal only takes you so far. It’s what comes after that matters.

‘Hyperrealism: This is Not a Body’ is at the Musée Maillol, Paris, until 5 March. ‘Things: A History of Still Life’ was at the Musée du Louvre, Paris from 12 October 2022–23 January).

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?