This review of ‘The Place of Many Moods: Udaipur’s Painted Lands and India’s Eighteenth Century’ by Dipti Khera appeared in the March 2021 issue of Apollo.

In around 1559 the Sisodias, Rajput rulers of the princely state of Mewar, moved their court from Chittorgarh to Udaipur. Unlike Chittorgarh, which was a fortress city built in a rocky terrain, Udaipur is a city of lakes and palaces, described in 1829 by the senior British administrator in the region, James Tod, in his Annals and Antiquities of Rajast’han as ‘the most romantic spot on the continent of India’. Tod went on to write that the Sisodias had ‘exchang[ed] the din of arms for voluptuous inactivity’. Although the supposed sensuality and idleness of Indian kings and princes was a common theme among British officials in the 19th century, it is true that, having expended much of their energy fighting the Mughals, the Sisodias enjoyed at Udaipur what Dipti Khera describes as a life ‘of pleasure and plenitude’. They promoted Udaipur as an ideal city, both geographically and aesthetically, and cultivated the arts of poetry, painting and music, making an almost moral virtue of connoisseurship. The paintings they commissioned in the 18th century depicted rulers at their leisure, not leading their men into battle, as in many Mughal paintings, but instead feasting and worshipping, contemplating their gardens, bathing with nobles or the court ladies, and in one splendid work feeding the crocodiles in the lake surrounding the island palace of Jagmandir. Khera’s principal thesis is that these paintings were intended to evoke a bhava, or mood, which is not simply the genius loci but something that draws the viewer in to share with the inhabitants what it was like to be lucky enough to live in the ‘City of Lakes’.

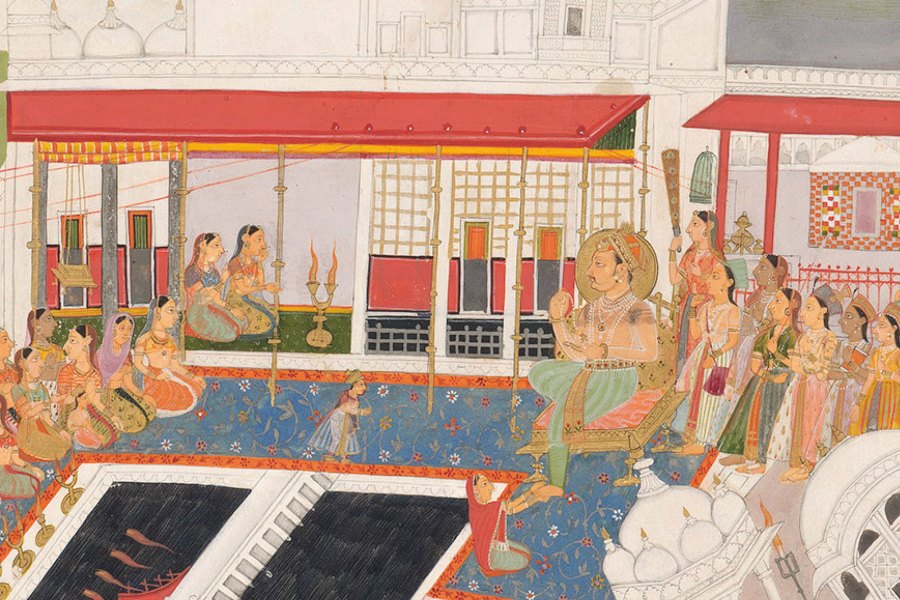

The Mood at Kota Palace (17th century), unknown artist. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

By way of illustrating how this was achieved, Khera takes two contemporaneous paintings of a palace not in Udaipur but in Kota, a city some 280km to the north-east and the seat of another Rajput court. One painting, The Palace in Kota (c. 1690–1700), was executed at Kota itself, the other, The Mood of Kota Palace (c. 1700), at Udaipur, and Khera suggests that ties between the two families that ruled these cities make it plausible that the Udaipur picture ‘constituted a deliberated response’ to the Kota one. The subject may be the same, painted from similar viewpoints, and both executed on paper in opaque watercolour and gold, but even if one takes into account the rather poor reproduction here of the Kota painting (it can be seen much more clearly on the Rijksmuseum’s website), they are very different in appearance and atmosphere. It is not merely that the Udaipur painter’s palette is more vivid and his outlines bolder; he has ‘transformed’ the Kota one ‘by changing the position and angle of the elevated vantage point and by juxtaposing various representational conventions’. Indeed, it is almost an exploded view of the same scene, in which the painter sets up ‘myriad vantage points to present a complex and busy picture of a courtly world that is a product of anamorphic stretching of the architecture’. The viewer is invited ‘to imaginatively wander through the palace, seeking the king. Tucked away in an upper corner of the bustling inner courtyard, he can be identified by a dazzling gold-colored halo’. The playfulness of this visual game of hide-and-seek reflected the pleasures of court life, and the painting provides the viewer with the immersive experience that is a defining characteristic of the later paintings of Udaipur itself.

Khera refers to ‘India’s long eighteenth century’, which she stretches beyond the years 1700–99, just as she usefully brings in other cities and regions to illustrate some of her points. For instance, she devotes several pages to what will perhaps be the most familiar artwork in the book, the Mewar Ramayana, which was the subject of a major exhibition at the British Library in 2008 and is now available in digitised form on the library’s website. This dates from 1649–53, but provides Khera with an example of an earlier Mewar ruler using art to enhance the Rajput’s claim to ‘ethical kingship’ by implicitly aligning his clan with that of the god-king Rama. Its depiction of Ayodhya’s palaces and gardens provides ‘a commentary on connoisseurs, aesthetics, and beautiful spaces’, and is thus a ‘pictorial genealogy for Udaipur’s investment in painted moods of beautiful places and urban ideals’. Khera also shows that the Udaipur painters were influenced by maps, one of the Fortified City of Ranthambhor dating from the reign of Jagat Singh of Jaipur (r. 1786–1818) providing an example that combines accurate topographical information with lively pictorial details, such as tiny monkeys attempting to scale the impregnable city walls, to create an artwork that is both practical and beautiful.

Maharana Amar Singh II in Udaipur during a Monsoon Downpour (c. 1705), unknown artist, Udaipur. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

One of the best chapters is about the monsoons. Until the 17th century monsoons were evoked in paintings through such iconographic elements as clouds and peacocks without any serious painterly attempts to recreate the actual feeling of rainfall drenching a landscape. Now painters used their skilful brushwork to depict raindrops spattering down from the clouds, bouncing off hats and umbrellas, forming rivulets that flow down to the bottom of the picture plane to collect in streams and lotus-filled ponds. In a largely desert state such as Rajasthan, the monsoon was both physically welcome and economically essential, bringing with it a feeling of wellbeing and prosperity. Paintings such as Maharana Amar Singh II in Udaipur during a Monsoon Downpour (c. 1705) were not just an opportunity for the painter to show off his skills, but also linked the replenishing rain directly to the ruler.

Elsewhere, like many academics, Khera is too inclined to tell us what she is about to say rather than just saying it, resulting in frequent repetition of material, and she too often uses jargon to say something simple in complicated ways. She is, however, at her considerable best when engaging directly with artworks. Here her writing becomes like a magnifying glass picking out details that might otherwise have gone unnoticed and explaining their significance.

The Place of Many Moods: Udaipur’s Painted Lands and India’s Eighteenth Century by Dipti Khera is published by Princeton University Press.

From the March 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home