From the July/August 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Van Leo, the professional studio photographer with unshakeable faith that he was an artist, is an impossible figure to place in the history of Egyptian culture in the 20th century. He sat on the edges of Surrealism, without ever really being a Surrealist; he ran one of the many photo studios that filled downtown Cairo in the 1940s and ’50s, but he was unlike any other studio photographer. His style was derivative and unique at the same time – a cross between Man Ray and a Hollywood glamour shoot, with an undefinable element that was all his own.

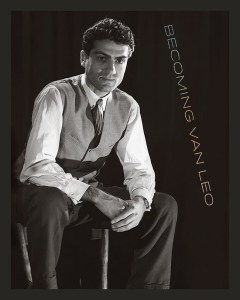

This year the Arab Image Foundation, after many years of research and collecting, has released a three-volume collection, Becoming Van Leo, telling his life story and reproducing a vast number of photographs. The huge endeavour spans his entire career and includes almost 2,500 photographs.

Van Leo was the name that Leon Boyadjian gave himself, apparently because of his admiration for the artist Van Gogh. He was born in Turkey in 1921 and moved to Egypt with his family in 1924. In the early 1940s, he and his brother Angelo set up a studio in wartime Cairo. From the very beginning they marketed themselves to members of the entertainment industry – dancers, actors and circus performers. They often offered their photographs without charge, in return for publicity, and their studio became known as the place for aspiring stars to get their photos taken. Van Leo went solo after a few years and continued to photograph Cairo’s cosmopolitan downtown nightlife scene.

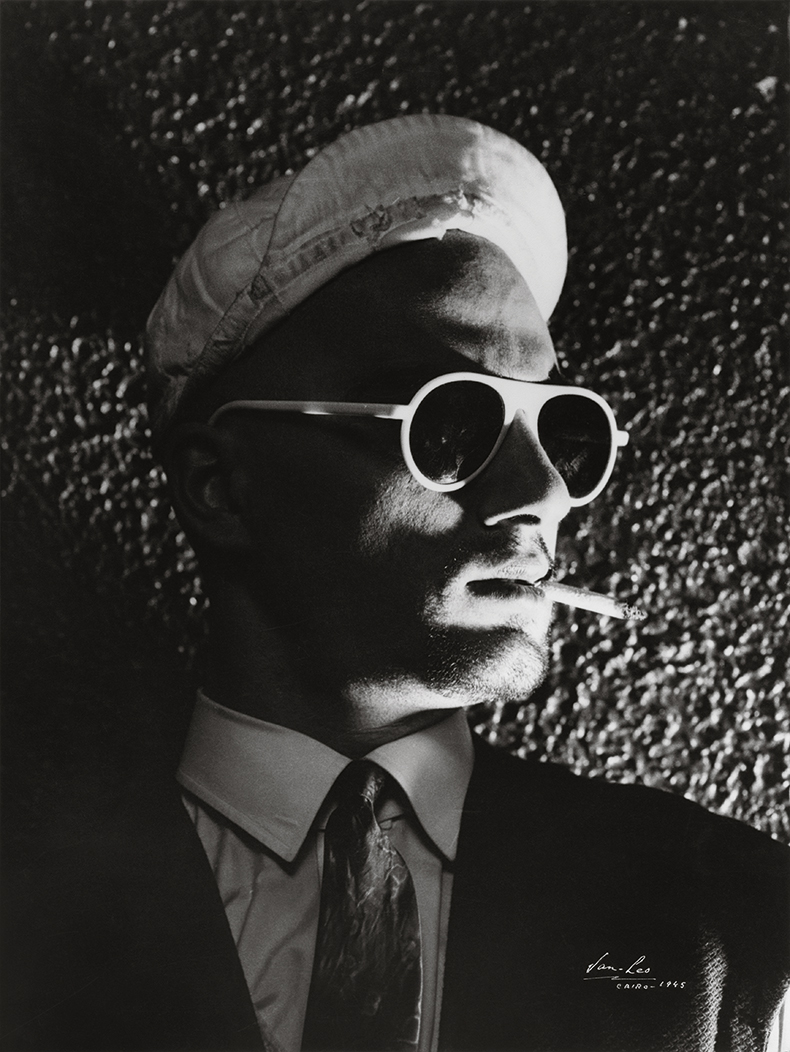

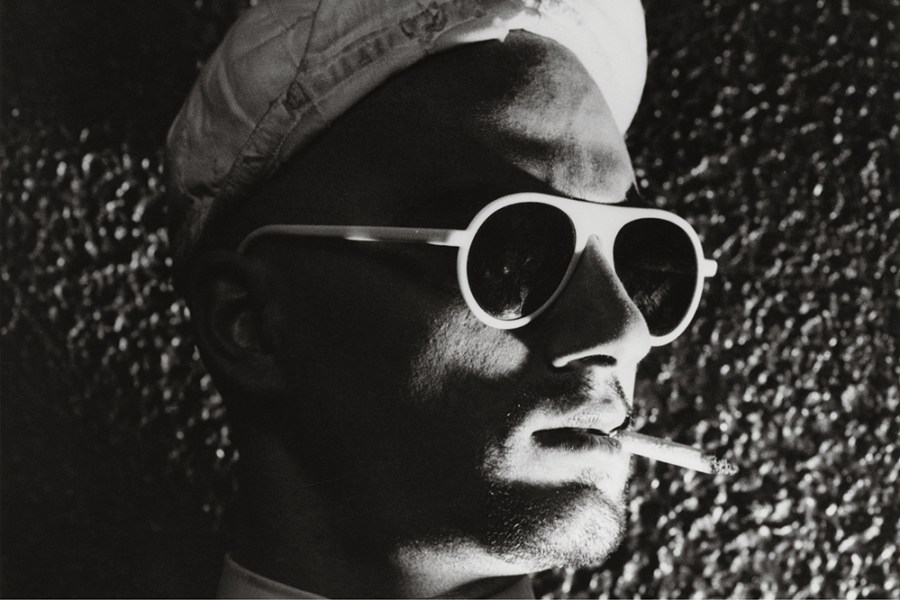

Self-portrait by Van Leo, taken in Cairo in January 1945. Photo: courtesy Arab Image Foundation; © 2022 The Angelo and Leon Boyadjian Family

The first volume of this book, which features hundreds of these photos, is a document of the Cairo that thrived in the mid 20th century. There are several pictures, for instance, of the famous Jamal twins – Jewish dancers and film stars – as well as some of the country’s best known movie idols. Van Leo’s lens captured a unique era in Egypt’s history, one that is now the subject of misty-eyed nostalgia.

But, really, Van Leo’s favourite subject was himself. The second volume is entirely dedicated to self-portraits taken throughout his life, from the young boy with a hint of a moustache on his lip to the grey-haired man sitting in his studio surrounded by his work. Van Leo took photos of himself in any guise he could manage – as a gangster, as a woman, as a Bedouin, as a pilot, as a sailor, as a highwayman. There are multiple-exposure photographs of him peering over his own corpse, and others of him in a loving embrace with a bust of Madame du Barry, the mistress of Louis XV.

Cover of ‘Becoming Van Leo’ by by Karl Bassil with Negar Azimi and Katia Boyadjian (Archive Books).

But who was ‘this perfect narcissist’ Van Leo? That is the question, above all, that this book sets out to answer. Who was the man behind the photos? What kind of life did he have? The third and final volume reproduces a generous selection of the photographer’s personal archive. Van Leo was undoubtedly a hoarder. The book transcribes and translates a trove of preserved letters, news clippings and other documents. It also adds interviews with family members and many people who met him over the course of his life.

Out of these documents and primary sources, an enigma emerges – an unusual man. The 1940s and early ’50s were his peak; he worked with a constant stream of performers from around the world. But as the years passed he became increasingly disillusioned with Egypt and the changes that were happening in it. He lamented the lost cosmopolitanism of his youth and the country’s increasing conservatism. At some point in his later life, during a fit of anxiety, he burnt a large collection of nude photographs he had taken, worried they could be used against him.

But, despite all his anxieties and complaints, he never left Egypt. His brother Angelo did and Van Leo himself made several applications to emigrate – to Canada and to the United States. But when the moment came, he could never leave behind his studio and his art. So, he lived on in Cairo as a ghost of the old times. Interviews in the book paint a picture of his later life: a faded relic encased in a time capsule off a busy street in downtown Cairo, surrounded by his work and suspicious of the outside world. By this point, Van Leo was hardly working, but he still insisted on maintaining a rigorous vetting process for clients. He only saw people with an appointment (even though he spent all day alone in the studio) and would agree to take pictures of them only after a detailed interview – sometimes more than one.

Van Leo never married – there is much speculation in this book and elsewhere that he was gay. His art, as Negar Azimi’s essay points out, has a large gay following and one of his most famous portraits is of the singer and gay icon Dalida. But his own sexuality remains the subject of unconfirmed speculation. This book makes no attempt to come down on one side or another. The Van Leo that emerges from the book was – and perhaps this is the most that we will ever be able to say – queer. He was unorthodox, unusual or, to quote Forster’s famous description of Cavafy, ‘at a slight angle to the universe’.

In his final years, Van Leo earned a cult following, which eventually led to wider recognition. In 2000 he received a prestigious Prince Claus Award, which honours artists and cultural practitioners across the world. Finally, his photography was being regarded as the art that he always insisted it was. But international fame came very late for Van Leo. He died in 2002. The riddles of his life and work will never be solved. This book may get us as far as it is possible to go.

From the July/August 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home