How many of us read Walter Scott for pleasure these days? In recent times – and even this year, in which we celebrate the 250th anniversary of Scott’s birth with walks, talks and a commemorative £2 coin – getting to the end of one of his three-volume tales has come to feel like an unusual feat of literary endurance. Yes, there are known enthusiasts – Rory Stewart is one; A.N. Wilson another – but on the whole fashion has turned Scott into a mountain that everyone has heard about but few wish to climb. And yet there was a time when it would have been odd not to be familiar with his novels. Far from being considered rambling and dull, his works were loved because they opened doors onto the past. Scott made history personal, emotional – inhabitable. He invented plausible characters and situations and fitted them deftly into the machinery of known historical events. And, indirectly, he shaped material culture to an extraordinary degree. ‘It would be worth while,’ wrote William Makepeace Thackeray in 1844, ‘for someone to write an essay, showing how astonishingly Sir Walter Scott has influenced the world; how he changed the character of novelists, then of historians, whom he brought from their philosophy to the study of pageantry and costume: how the artists then began to fall back into the middle ages and the architecture to follow.’ We might not accept the more extravagant of Thackeray’s claims, but we see what he means.

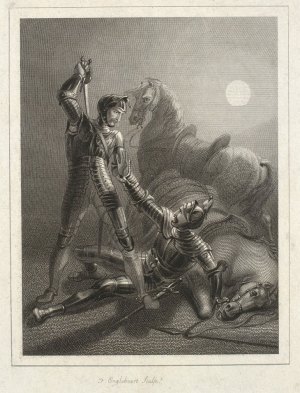

A Scene from Walter Scott’s ‘The Talisman’ (c. 1840–60), Charles Landseer. Sunderland Museum & Winter Gardens

Many hundreds of paintings and an incalculable number of reproductive prints attest to the 19th-century passion for the Scottish writer. The first stirrings coincided with a fast-growing market for attractive, small-scale pictures for the middle-class home with subjects taken from popular literature. The artists who rose to meet this demand did not, according to Thackeray, aim ‘at subjects which the world is pleased to call great, viz. tales from Hume or Gibbon or royal personages under various circumstances of battle, murder, and sudden death’. ‘Lemprière, too, is justly neglected,’ he continues, ‘and Milton has quite given place to Gil Blas and The Vicar of Wakefield. The heroic, and peace be with it! has been deposed.’ If you wish to investigate the particular literary territory mined by the creators of pictures for the parlour, then you can hardly do better than to visit Room 82 at the Victoria and Albert Museum. There, among the densely hung gilt frames, you will find scenes from Shakespeare, from Molière, from Burns, Goldsmith and Sterne. Ariel flies by on a bat’s back (Joseph Severn) and Autolycus sells song sheets (Charles Robert Leslie); proud Maggie refuses Duncan Gray’s marriage proposal (David Wilkie) while the widow Wadman lays siege to Uncle Toby (Leslie again). Among the V&A’s 19th-century genre paintings you will also, of course, find Scott – in the form of William Powell Frith’s The Bride of Lammermoor (c. 1852). Edgar and Lucy stand together at the fountain tenderly exchanging halves of a broken gold coin as a love token, forever suspended in a moment that, for the viewer familiar with the story, is tinged with impending doom by knowledge of the book’s tragic end – literary subjects are nothing if not flattering to the viewer-reader.

An engraving illustrating a scene from Walter Scott’s poem Marmion (1809), Richard Westall. Corson Collection, Edinburgh University Library. Photo: © The University of Edinburgh (CC BY 3.0)

Scott’s works offer a seemingly endless array of picturesque incident, from high comedy to pageantry, battle scenes to sentiment, and his detailed descriptions of costume and interiors extend an open invitation to artists. ‘I will sit on this footstool at thy feet,’ declares Amy Robsart to her husband the Earl of Leicester in Kenilworth (1821), ‘that I may spell over thy splendour, and learn, for the first time, how princes are attired’ – thus giving scope for the Earl’s rich costume to be described in almost fetishistic detail. In The Antiquary (1816) Scott even bids the reader to imagine the home of the Mucklebackits as though they were looking at a painting by his friend David Wilkie: ‘In the inside of the cottage was a scene, which our Wilkie alone could have painted, with that exquisite feeling of nature that characterises his enchanting productions.’

Scott could, however, have a tricky time with his illustrators. He was privately critical of Richard Westall’s pictorial embellishments for two of his works in verse, The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805) and Marmion (1808), writing that ‘if Westall who is really a man of talent fail’d in figures of chivalry where he had so many painters to guide him, what in the Devil’s name will he make of Highland figures. I expect to see my chieftain Sir Rhoderick Dhu in the guize of a recruiting sergeant of the Black Watch and his Bard the very model of Auld Robin Grey upon a japand tea-tray.’ And in 1831, when J.M.W. Turner was commissioned to paint watercolours to be reproduced in a new edition of Scott’s Poetical Works, he was so reluctant to visit Scotland that the author was obliged personally to invite him to stay at Abbotsford.

From 1805 until 1870 more than a thousand paintings on themes from Scott were exhibited at the Royal Academy and the British Institution, and artists from John Martin and Edwin Landseer to John Everett Millais and William Quiller Orchardson mined his works. Scott was even more popular in France; in 1830 his works accounted for a third of all novels published there. Victor Hugo wrote a play based on Kenilworth and declared Ivanhoe, his novel of 1819, to be ‘the true epic of our age’. In 1823 the young Eugène Delacroix painted Rebecca standing at the window of the wounded Ivanhoe’s chamber, bravely giving him a blow-by-blow account of the battle taking place just outside – it is another picture that relies on the viewer also being a reader. In 1846 the artist returned to Ivanhoe with The Abduction of Rebecca; this time, though, the picture has none of the same antiquarian, picturesque qualities, but is a dynamic swirl of limbs and muscle, drapery and flame whose subject could be grasped by anyone, regardless of whether or not they spent their evenings engrossed in the Oeuvres complètes de Walter Scott.

The Abduction of Rebecca (1846), Eugène Delacroix. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

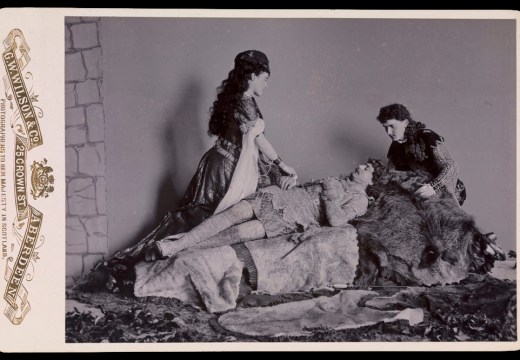

Around 90 opera libretti are based on poems and novels by Scott, and there were countless plays, six different productions of Ivanhoe appearing in London in 1820 alone. Adapting Scott’s works for the stage could also be a do-it-yourself affair; their general familiarity made them second only to Shakespeare when it came to amateur theatricals. Among the most lavish of these was a series of tableaux vivants enacted at Hatfield House in January 1833 for Lady Salisbury, which Wilkie designed and supervised. ‘Amongst the tableaux,’ reported The Times, ‘one of the most remarkable was that taken from the description of Ivanhoe, where Rebecca, to avoid the pursuit of the knight, threatened to throw herself from the battlements of the castle. Lady Lyndhurst, covered with jewels, and looking remarkably well, personated Rebecca, and Lord Grimston the Knight.’

Scott himself could also be said to have created one of the greatest theatrical events of the 19th century when he was tasked with organising George IV’s visit to Scotland in August 1822. For the ceremonies, pageants, parades and balls he insisted that all gentlemen should wear kilts as a visible symbol of Scottish identity, despite the fact that at the time it was highland dress and so not appropriate for lowlanders. Used to reimagining historic events, on this occasion Scott created one.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home