Crystal Bennes heads to Helsinki in the latest part of her series about museum storage collections and the art hidden away inside them

The imposing symmetry of the Ateneum Art Museum’s 1887 building in Helsinki, just across the street from Eliel Saarinen-designed railway station, houses Finland’s national collection of art from the mid 18th century to 1960. As with many national art collections, the works over-run the building and spill into storage. The Ateneum’s storage facilities house the majority of the 20,000 works that comprise the institution’s collection, as only about six per cent of the collection is on display or loan at any one time, and objects in store are divided across a number of sites.

The one I visit, accompanied by museum director Susanna Pettersson and head of conservation Kirsi Hiltunen, is principally used to house works as they shuffle between temporary displays in the exhibition galleries and overseas loans. Having said that, our visit unearths at least one gem which has, according to exhibition records, never been publically displayed in the galleries, so variation abounds.

Unlike the previous two visits in this series – to the Hermitage and the Scottish National Galleries – the Ateneum is a considerably younger collection, acquired with altogether less money, but no smaller ambition. Far more than in the previous two visits, this trip has revealed in store a number of works which describe the history and development of the museum itself.

Founding the collection

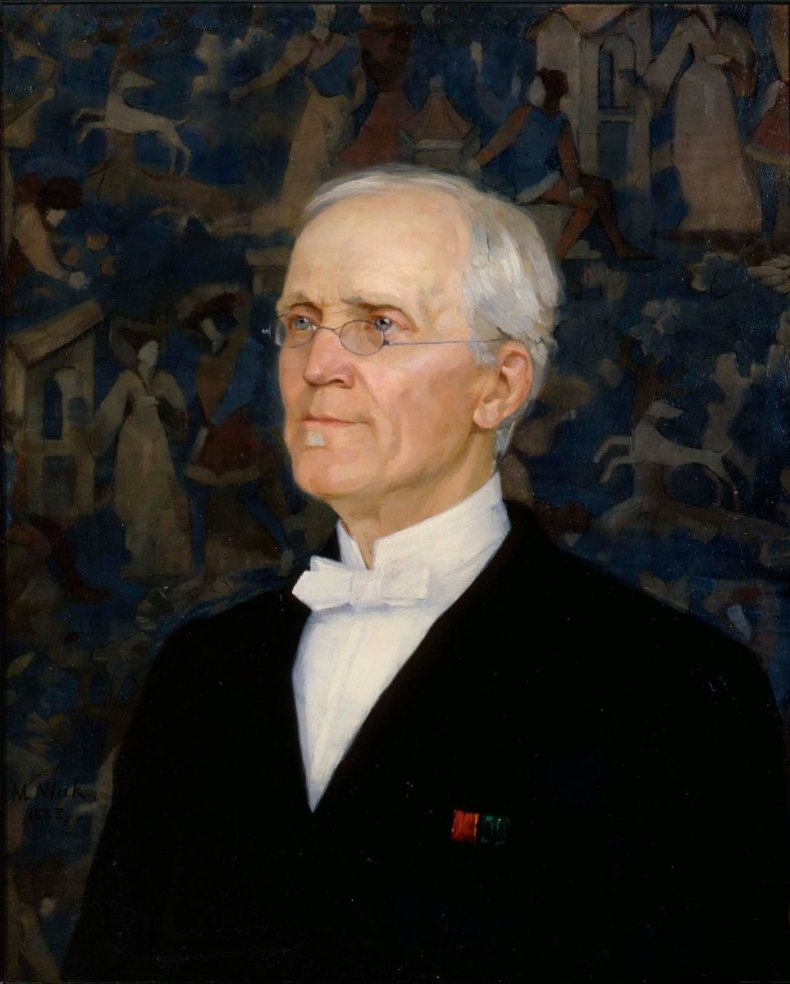

Portrait of B. O. Schauman (1888), Maria Wiik

Portrait of B.O. Schauman (1888), Maria Wiik. Finnish National Gallery

This portrait of the first keeper of the Ateneum’s collection, commissioned by the Finnish Art Society in 1888, represents a noteworthy trend in the early years of acquisition for the collection, namely the high number of works by female artists. Wiik studied at the Drawing School of Helsinki in 1874–75, moved to work and train in Paris, and won a bronze medal at the 1900 World Expo for her painting of two women, Out into the World. Schauman had previously worked for the Helsinki University Library and was encouraged to put the experience to work in his new post – he compiled the first inventory of the collection and published the first collection catalogue in 1873. Alas, his portrait, which has not been exhibited in the museum since 1954, remains in storage for most of the time.

Building the collection

Copy of Velázquez’s Infanta Margarita Aged Three (1894), Helene Schjerfbeck

Copy of Velázquez’s painting Infanta Maria Teresia (1894), Helene

Schjerfbeck. Finnish National Gallery

While the Cast Courts of the Victoria and Albert Museum are celebrated, lesser known are other late 19th-century strategies for ‘filling the gaps’ in European national collections, such as those employed at the Ateneum. Conscious that the museum lacked the funds to purchase a ‘complete’ collection to tell the story of Western art, Carl Gustaf Estlander, the first chairman of the Finnish Art Society, implemented a programme whereby young Finnish artists travelling abroad would be commissioned to duplicate artworks from a master list of 1,200 items. In 1894, Schjerfbeck received a travel grant to copy the Infanta Margarita from the original in the Kusthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the piece was acquired for the collection that same year. In an 1894 letter to Maria Wiik – the artist of the Schauman portrait above – Schjerfbeck wrote, ‘I am more and more fascinated by the paintings of the past. The old masters are a revelation when you study them patiently, for a long time, and copying is the best way of doing that.’

Shifting collection objectives

Miss Heckford (1757), Isak Wacklin

Miss Heckford (1757), Isak Wacklin. Finnish National Gallery

‘There’s nothing wrong with the picture,’ says Dr Pettersson as we pull out the rack which includes this portrait, ‘but stylistically it just doesn’t fit with the rest of the Ateneum’s current collection display.’ The rococo plays very little part in the history of Finnish art and Wacklin himself remains something of a mystery. He studied portrait painting at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts between 1731–34; in 1743 he applied for a passport to travel to St Petersburg, and he died in Stockholm in 1758. The portrait of Miss Heckford, with its English undertones, was discovered in London in 1920 by the then Finnish minister to London and acquired for the collection the following year.

Forgotten, but not forever

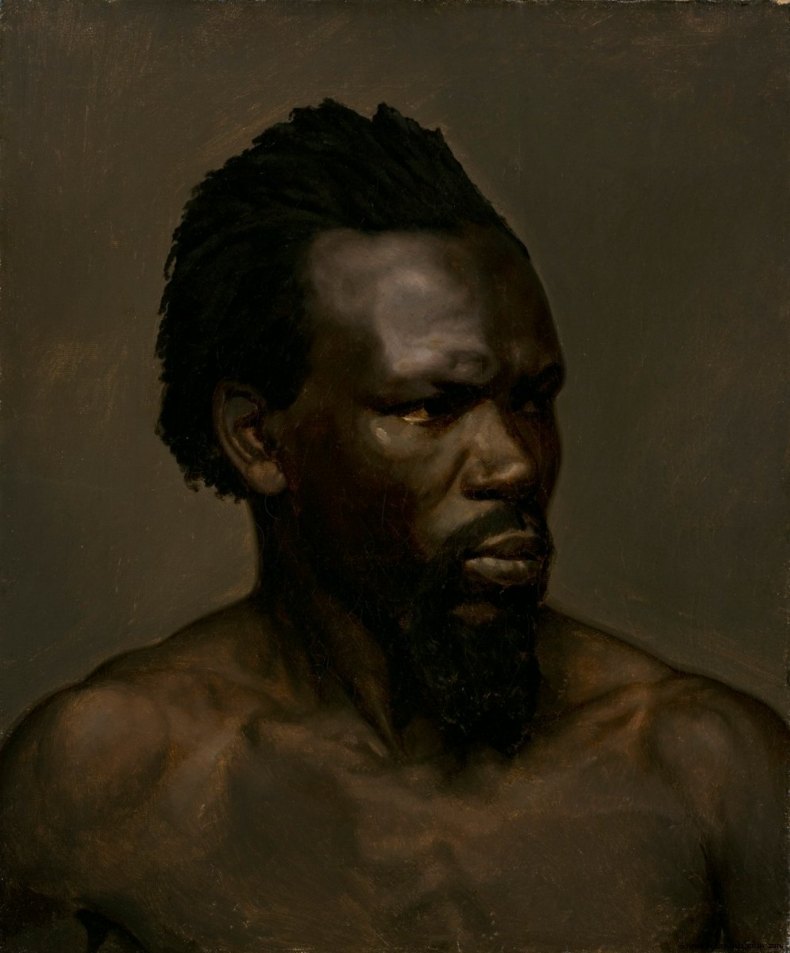

Bust portrait of a black man (n.d.), Nils Jakob Olsson Blommér

Bust portrait of a Black Man (n.d.), Nils Jakob Olsson Blommér. Finnish National Gallery

This handsome portrait by Swedish painter Nils Blommér, better known for his romantic scenes of Norse mythology, was acquired for the Finnish Art Society in 1862, nine years after the artist’s death. The picture appeared in a Finnish Art Society Exposition in 1867 before languishing in storage for many years. When curators began to determine which pieces should be included in Stories of Finnish Art, a recently opened salon-style permanent display (until the end of 2020). Pettersson explained that they laid out selected works in date order, mainly to avoid hanging all of the gallery’s usual suspects. This portrait, whose sitter remains unknown, was rediscovered in the stores during that process and can now be admired in room 17.

Historically important, but stylistically out of favour

Galatea’s Triumph (1840), Berndt Abraham Godenhjelm

Galatea’s Triumph (1840), Berndt Abraham Godenhjelm. Finnish National Gallery

Everyone laughs as we pull out the rack and this picture appears. Its highly stylised, flat theatricality feels out of place next to the muted tones and natural scenes of much else in the stores. It compares particularly unfavourably with a rapidly sketched portrait of a young girl just above it – Franz von Stuck’s Portrait of the Artist’s Daughter Mary (acquired in 1909 and displayed only once since then in 2000/1). Although not especially interesting to look at, the picture’s history is intertwined with that of the collection. Having studied in Saint Petersburg, Godenhjelm was appointed the first drawing teacher at the Finnish Art Society (FAS) drawing school, from 1848 to 1869. Unlike many important figures in the foundational years of the FAS, Godenhjelm’s self-portrait was donated rather than purchased, and the late purchase date of this picture, in 1899, 18 years following his death, perhaps reflects the extent to which his style had already fallen out of favour by the end of his life. Galatea last saw the light at the Ateneum in 1996/7 in an exhibition celebrating the 150th anniversary of the Finnish Art Society.

Missed collection connection

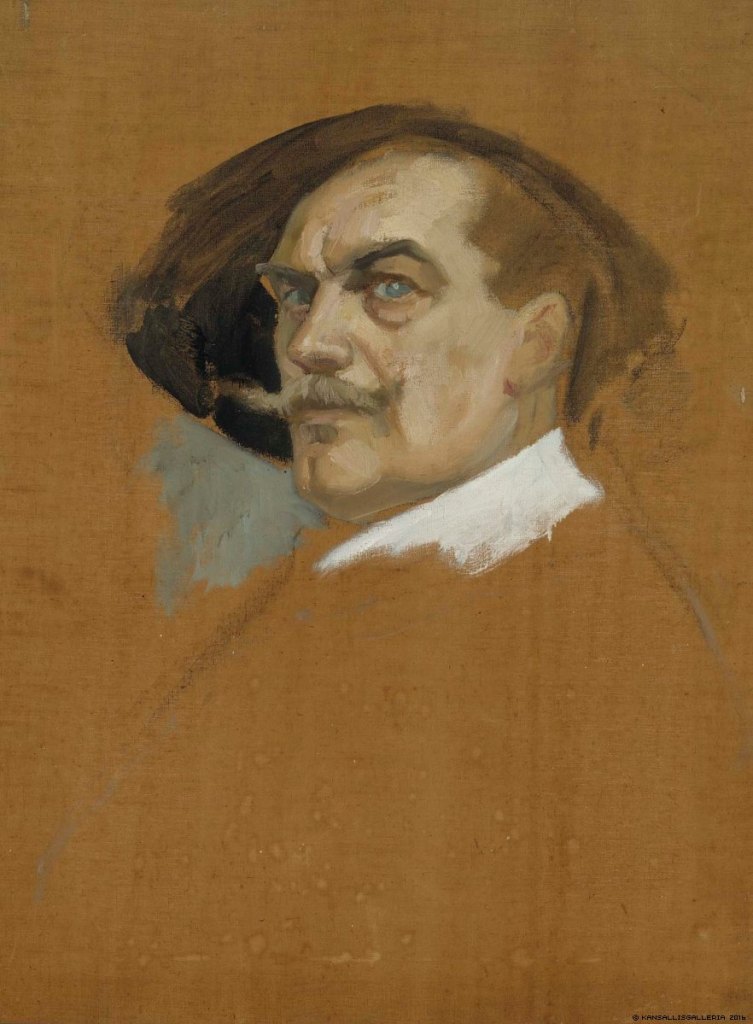

Self-Portrait in a Dress of the 17th Century, study (1904/5), Albert Edelfelt

Self-Portrait in a Dress of the 17th Century (study), (1904/5), Albert Edelfelt. Finnish National Gallery

Nearly 7,000 items in the Ateneum’s collection are by the painter Albert Edelfelt, so it is no surprise to some of his works in the stores. It was a surprise, however, to discover this unfinished study for a self-portrait. More surprising still was to learn that it had not been exhibited since being donated by the family of a noted Finnish collector in 1965. While one might assume that the Rembrandt-esque study was in preparation for another, completed (and more widely displayed) picture also in the Ateneum’s collection – Self-Portrait in 17th Century Costume – this preparatory sketch has been dated by the museum to 1904/5, while the finished self-portrait dates to 1889.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home