Over the course of his career, the Scottish printmaker and painter Willie Rodger (1930–2018) observed almost everything about us and the world we’ve made, and he got it all down on paper. According to his son, he never went anywhere without his A5 sketchbook – ‘except, perhaps, to bed’. From those sketches he was able to pull, like rabbits from a hat, an oeuvre astonishingly warm, shrewdly observed and technically perfect.

In any picture by Willie Rodger, there are three constants. The composition will be unexpected. The approach, at first intellectual and reasoned, is yet playful. And there will be a fantastic amount of movement that gives even inanimate objects a sense of humour. The works in ‘Life’s a beach!’ at the Open Eye Gallery are vacations, or staycations, in themselves.

A pen-and-ink drawing, Busy Beach Scene (1987), is a conglomeration of folk doing everything you can do at the beach: they’re reading, lying on their tummies, on their backs, kissing, carrying stuff, talking, checking each other out, ignoring each other, saluting, arriving, departing, wearing much, wearing little. In short, they’re luxuriating.

Wish You Were Here (1970), Willie Rodger. Courtesy of Open Eye Gallery

Wish You Were Here (1970) is a picture reminiscent of the posters for surf movies such as The Endless Summer or Big Wednesday. Rising above a white, tan and black striped canvas windbreak, a tanned woman in a black-and-white bikini adjusts her Jackie O style sunglasses. Rodger’s superb titles often suggest a question: is the artist taunting you because you’re not there on this beach with this woman? Or is she wishing you were?

In Harbour Wall (1971), two people have parked their arses on an uncomfortable mass of stonework and are looking out to sea. Restful slouches, perhaps with that resignation that comes at the shore when you realize you have the entire day ahead of you. There’s another story in The Beach – His and Hers (1971). The he and she aren’t here at the moment, so we’re left to stare at their folding chairs. This is one of a number of prints executed on kraft paper – instant sand – on which Rodger is able to impose a number of different atmospheres. The Beach and Enjoying Yourself? (1970) have a definite heat haze – created with the artist’s choice of pale inks. The Beach is made up from what were originally separate linocuts. The grouping of the figures couldn’t be beachier.

There’s a hint of the story of men and women across several of the pictures involving windbreaks – in Beach Combing (1992), a gorgeous chap is cosily reading, reclining against his canvas, as a lustful woman peeks over it, surveying him. In Husband and Wife on Holiday after 20 Years of Marriage (1969), she is reclining in the sun on a flowery beach chair. He, on the other side of the windbreak, facing away, is merely the back of a head.

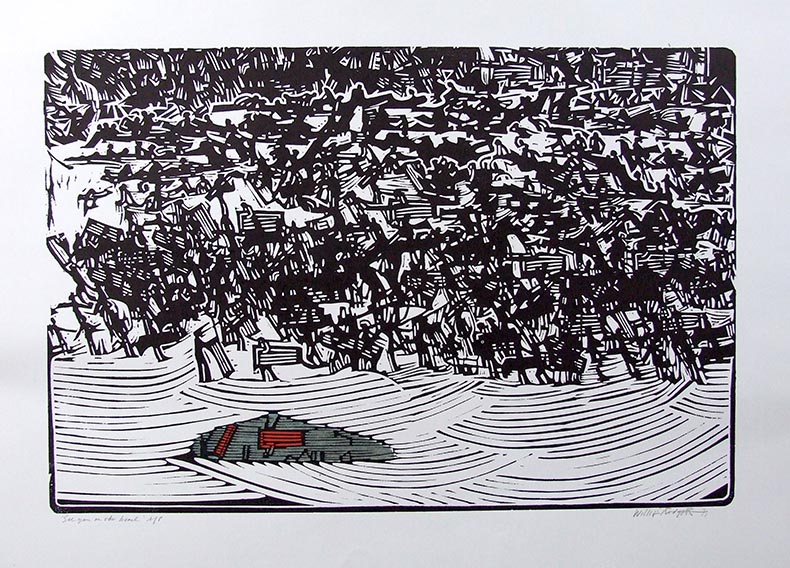

Perhaps the most involving and complicated picture here is See You on the Beach (1971), a wondrously large linocut that could be a feature film. The upper part of the frame is a tumultuous storm of beachgoers lying on towels, adjusting their windbreaks, toting Lilos, schlepping chairs. There is a rush of energy in this picture, as if these people have been magnetised and drawn, helplessly, down to the ocean. In the foreground, a few yards out in the water, there is the single colourful reflection of a solitary trudger with his stripy raft. Life at the beach isn’t always easy – this manic scene could easily be Coney Island, not Coldingham Sands.

See You on the Beach (1971), Willie Rodger. Courtesy of Open Eye Gallery

Rodger has a special way of deconstructing towns. He twists them, just a little, in order to show off their beauties, and he can impart an inviting ramshackle quality to things that are not necessarily ramshackle. You are reminded of Joan Eardley’s precipitous Catterline cottages or James Dixon’s pictures of Tory Island. In A Corner of St Abbs (1993) he pays particular attention to the surfaces of its houses in bright sun – stone, dash, metal, brick – along with a contentedly rambling figure in sea boots that may be the artist himself. He draws us through the village again in Down to the Harbour, St Abbs (1995), and does something similar in an oil painting of Eyemouth, an intricate take on the geometries of a Scottish town and its roofs, both of tile and slate. And in a very large oil, Bathsheeba (1998), a woman sunbathing on a rooftop is subsumed by a raging red sunset and a totally tipsy scattering of the whole townscape of Glasgow.

One of Willie Rodger’s favourite movies was Jacques Tati’s Les Vacances de M. Hulot. There is an oil here, Good Morning, Miss Travers (1993), in which people seem to have to file dutifully past a woman royally ensconced in several windbreaks who must surely be the matriarch of the sands. In Packing Up (1995), a bleary group of four are heading back to the boarding house, laden with pails, chairs, blankets, bags, nets, bats and balls. It always seems so much more stuff at the end of the day. French Service (1995), a large drawing in black conté, could have been made to order for Tati: it’s a couple of umbrellas above a jumble of chairs and café tables laid with white cloths. No one can draw tables and chairs like Willie Rodger. He makes them humane.

‘Willie Rodger RSA RGI (1930–2018): Life’s a beach!’ is at Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh, until 28 May.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has arts punditry become a perk for politicos?