It is easy to see why the Ben Uri has chosen Ceremonial Dance (1927) for the poster of its new exhibition, ‘Sheer Verve’. The work by Orovida Pissarro is at once exuberant and coolly elegant, an oriental fantasy that fuses energetic human figures and a quartet of serene animal observers. Exhibited at the Women’s International Art Club (WIAC) in 1927 and again in 1928, it distils its creator’s love of Chinese painting as well as the arts of Japan, India and Iran. Famously independent – and keen to go beyond the Impressionist and Post-Impressionism associated with her family – Orovida went by her first name alone. Downstairs, in the same exhibition at Ben Uri, we find a much later example of her work: Refugees (1947) is a picture of children from different continents and conflict zones that speaks of hope in the post-war world.

Orovida is but one of the many exciting and unconventional female artists who exhibited through the art collective at the heart of ‘Sheer Verve’ (the title is taken from a review by the critic Bettina Wadia in 1963). Founded in Paris in 1898, the first exhibition of the WIAC was held two years later at the Grafton Galleries, that centre of modernism in Edwardian London. Given their historic exclusion from art institutions, the club’s creators recognised the need for networking opportunities among professional women artists, as well as spaces for mutual support. In defiance of assumptions about appropriate ‘feminine’ genres and subjects, they embraced internationalism and the experiments of the avant-garde. Despite the doubters, by 1904 the WIAC numbered 150 members.

Caliban (1945), Eileen Agar. The Reiff Collection of Modern British Art. © The Artist’s Estate/Bridgeman Images

The founders were British and American women whose cultural horizons were Anglophone, and whose vision of internationalism overlapped with the geographies of British imperialism. In the eight decades of its existence, the club counted six South Asian women as members, including the Bengali artist Sunayani Devi. (By coincidence, Devi’s sister was painted by Clara Klinghoffer in the very first work by a female artist acquired by the Ben Uri.) Despite the relative lack of ethnic diversity, the organisers of the club made a conscious effort to widen the artistic conversation in London by inviting foreign artists to exhibit. In 1911, the WIAC reached out to the Austrian Association of Women Artists (VBKÖ); in 1914, there was even a display of beadwork by Native American women, in keeping with the club’s interest in the early years in the decorative arts and textiles.

Partly because membership was restricted to professional artists, the club was more egalitarian in its structures than the Society of Women Artists (helmed for many years by Laura Knight), which counted many amateurs among its ranks. It also celebrated a lineage of female artists by including, as early as 1910, a historical section featuring Rosa Bonheur and Sofonisba Anguissola. For 20 years the president was Ethel Walker, a Scottish painter whose work featured prominently in ‘Queer British Art’ at Tate Britain in 2017. As well as the example of Orovida, Ben Uri displays a sculpture by Marlow Moss, the constructivist who had dropped her birth name of Marjorie in 1919, and was a founder member of the Abstraction-Création Group. The spheres and coil of Moss’s brass sculpture of 1953 unmistakably evoke the atomic age.

Construction Spatial (1953), Marlow Moss. Private collection. Photo: Ben Uri Gallery and Museum; © The Estate of Marlow Moss

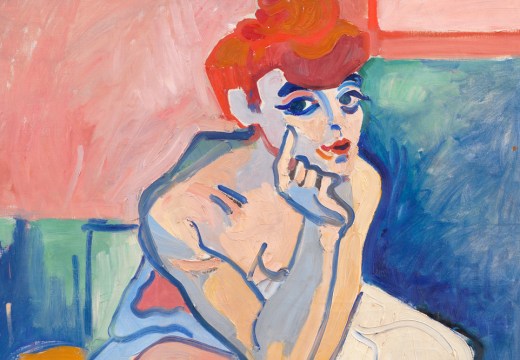

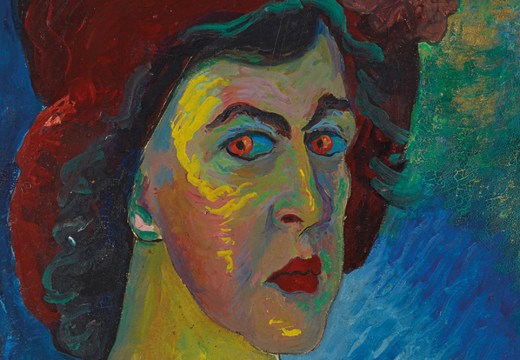

The Ben Uri is an ideal venue to explore the club’s history. Many of the Society’s members also exhibited with the WIAC and an impressive proportion of female artists are represented in the permanent collection (29 per cent). Around half the works in ‘Sheer Verve’ come from the Ben Uri’s own holdings, with some fine loans of works by other major figures: Gwen John, Laura Knight, Prunella Clough, Elisabeth Frink, Wilhelmina Barnes-Graham and Vanessa Bell (represented here by a lovely still-life painted in Charleston). Eileen Agar is represented by Caliban (1945), an iridescent mix of oil and collage suggestive of coral and shells. The fury and intensity of Paula Rego, who exhibited with the WIAC in 1961, is distilled in Hungry Dogs (1965), on loan from Victoria Miro gallery. Inspired by a story Rego noted in the Barcelona press that the Franco regime had been poisoning street dogs, it is both seductive and disturbing in its kaleidoscopic use of colour and contorted forms.

The lesser-known names are just as compelling. Upstairs in the exhibition is a knock-out portrait of a woman in a red hat by Stella Steyn. Born to Jewish parents in Dublin, Steyn had been asked by James Joyce to teach art to his daughter Lucia and to illustrate Finnegan’s Wake; in 1931, she became the first Irish artist to enroll at the Bauhaus. Downstairs, the versatility of émigré artists is on display: the WIAC provided a platform for many painters who had fled Nazi Europe, ranging from Else Meidner (represented here by a textured portrait of an older woman) and Halina Korn to Grete Marks (the Bauhaus ceramicist and painter, who recently featured in an exhibition at Pallant House). Actaeon Devoured by his Hounds (1968–69) is a savage take on Greek mythology by Janina Baranowska, the Polish-born artist and pupil of David Bomberg, who died last year. Sculpture deserves special mention. Take the bronze portrait busts of Elsa Fraenkel, who had created sensitive renderings of ethnic types in Germany and Paris, or the tender plaster figure of Maternity by Erna Nonnenmacher, who came to Britain from Berlin in 1938 and was briefly interned on the Isle of Man, before she became involved in anti-fascist causes.

Maternity (c. 1940s), Erna Nonnenmacher. Ben Uri Collection. Photo: Ben Uri Gallery and Museum; © The Estate of Erna Nonnenmacher

The multiple connections between artists and sitters in ‘Sheer Verve’ – Nonnenmacher and Fraenkel exhibited together at the Ben Uri in 1947, for instance – creates coherence among works that are notable for their stylistic variety. Judging from this selection, the WIAC was an artistically inclusive outfit, with examples of Expressionism, Surrealism or abstraction displayed side by side. What also unites all the work here is a sense of conviction and experiment. Despite the efforts of some of its notable late champions, such as Halima Nalecz, owner of Drian Galleries, and Christiane Kubrick, the club could not come back from the loss of Arts Council funding and eventually folded in 1978. But its championing of women artists for 80 years is remarkable, and congratulations are due to curator Sarah MacDougall and to researcher Una Richmond for recovering some of its achievements. This exhibition is timely, original and bursting with the ‘sheer verve’ of its title.

‘Sheer Verve’ is at the Ben Uri Gallery and Museum, London, until 15 December.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home