What is a fake building? Unlike artworks, buildings aren’t faked for short-term or financial gain; they cost too much and take too much time to build for that. And for the most part they are highly visible, so their provenance is much harder to hide. To speak of fakes in relation to buildings is to talk about a lack of authenticity rather than deliberate deceit. Authenticity can imply a number of things. In the case of a building completed after an architect’s death or without their blessing, it can mean the lack of the author’s guiding hand. The posthumous construction of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s House for an Art Lover, a prize-winning design from 1901 that was finally realised in the 1990s, is a case in point. It can also apply to a building that has been substantially rebuilt or entirely reconstructed. In recent decades a small number of significant ‘lost’ buildings, such as the Frauenkirche in Dresden and the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, have been reconstructed, usually for political rather than aesthetic reasons.

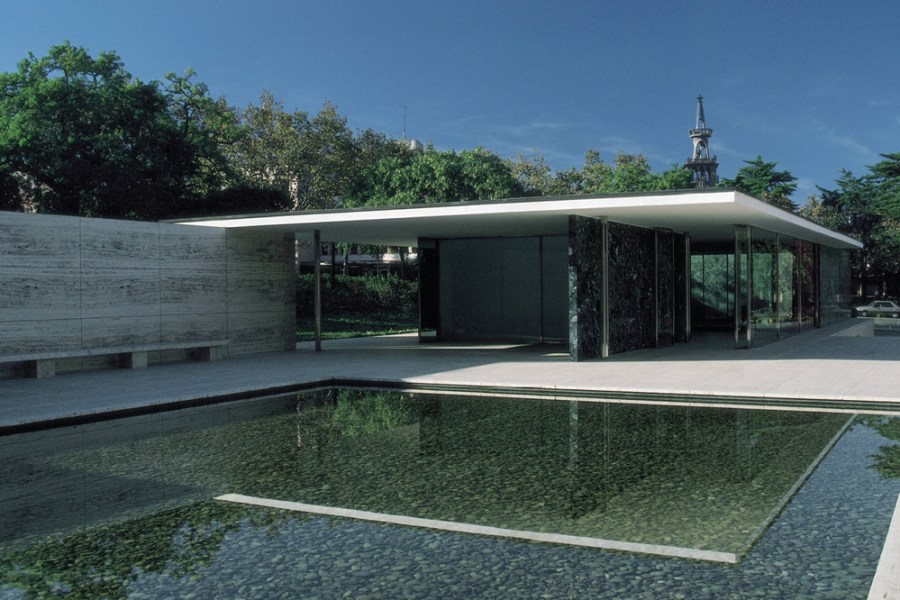

The process of reconstruction is generally, but not always, reserved for pre-modern buildings. The Barcelona Pavilion, as it is commonly known, was originally constructed as the German Pavilion at the International Exposition of 1929 in Barcelona. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich, the pavilion lasted less than a year before it was dismantled. Despite, or perhaps because of this short lifespan, it came to assume a hugely important status in the history of modern architecture. The ‘new’ Barcelona Pavilion, which was built in the 1980s, is a faithful replica that sits in exactly the same position in Montjuïc as the original, made of the same materials and finished to a high degree of craftsmanship. Yet even a faithful reconstruction is problematic. Wasn’t modernism meant to be about shaking off our sentimental obsession with the past? What is modern about reconstructing a 50-year-old building?

Row of half-timbered houses (‘Ostzeile’) on the eastern side of Römerberg Square, Frankfurt, reconstructed in the 1980s. Photo: Thomas Kienzle/APF via Getty Images (2020)

Architecture, however, is a collaborative art and buildings are the work of many hands. The only thing that an architect actually makes is drawings and so, in a sense, a drawing can be built at any point and remain the same. That is unless one subscribes to the idea that architecture should be an authentic reflection of its times. Authenticity in this sense is about a building’s relationship to time and place. The belief, central to modern architecture, that buildings should embody the spirit of the age assumes that they are the logical outcome of the contemporary forces that bring them into being. Such a belief is clearly antithetical to reconstruction. To be authentically modern, one can’t recreate the past.

In his recent book, Fake Heritage: Why We Rebuild Monuments (Yale University Press), John Darlington looks at historic reconstructions, copies and invented historical structures. He begins with an account of Piltdown Man, a notorious archaeological hoax in the early 20th century, before discussing a number of examples of ‘fake heritage’ in which the line between authenticity and artifice is much harder to establish.

Darlington considers the blatantly inauthentic faux-ruins of the 18th century as well as the educational copies of genuine artefacts in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s ‘cast courts’. There are also buildings, or bits of buildings, that have been reconstructed after suffering collapse, such as the campanile of St Mark’s Square in Venice. And there are the recreations of whole parts of cities, such as Römerberg Square in Frankfurt, which were destroyed by bombing. The book comes up to date with the parodic versions of public schools and their grounds that Harrow and Dulwich College, for example, have exported to China.

There are subtle shifts in emphasis and intent in all these examples. The invented ruins of 18th-century estates may have been intended to confer legitimacy on newly created landscapes but they are also, at least to modern eyes, pieces of fantasy. Classical architecture abounds in copies and versions of ideas that were clearly not conceived of as fakes by their authors. The dissemination of Palladio’s books on architecture, for instance, resulted in numerous interpretations of his work from the 18th century to the present day that are closer to cover versions than copies. Which begs the question: is a neo-Georgian country house built in 2020 a fake, or merely the latest step in a long line of development?

The buildings of the post-war architect Raymond Erith were genuine in the sense that they were designed with conviction and demonstrate a subtle understanding of classical architecture. But they also deliberately obscure issues of provenance. His design of 1951 for Devereux Farm in Essex has the appearance of a house that has been adapted over time, as many old houses have been. Devereux Farm, however, was designed in one go. This ‘false archaeology’ is a form of fakery though its intention might be to create a genuine sense of continuity with the past.

Photo: Christopher Hope-Fitch/RIBA Collections (2008)

A far more ambitious recent example of fake history is Poundbury, the new town built on the edge of Dorchester by the Duchy of Cornwall. Originally master-planned by Léon Krier as a contemporary copy of an 18th-century market town, Poundbury with its more recent buildings offers an eclectic grab-bag of past styles, resulting in a curious collapsing of architectural history. Faux-industrial wharf buildings that are nowhere near water contain purposely designed loft apartments that were never lofts. Future phases of development will march shamelessly forward into the past with late 19th-century and Arts and Crafts-styled buildings. But does it matter? Ben Pentreath, the designer of much of Poundbury’s recent development, might argue that concerns about authenticity are a hang-up inherited from modernism. If genuine former wharf buildings have proved effective as loft apartments, why not cut out the intervening 200 years and build them from scratch?

Poundbury is interesting because it is not a reconstruction nor is it a straightforward copy. Arguably, its eclectic recent trajectory renders the earlier phases of careful neo-Georgian more inauthentic, merely another stop-off point in a history-tour of architecture rather than the model town envisaged by Krier. We are used to the idea that architectural styles progress, developing in relation to external forces before becoming redundant. Conventional art history has it that architecture is part of a continual progression, forever staking out a new future. Darlington’s book and the examples detailed here offer an alternative view, one where architecture is equally obsessed with remaking its own past.

From the December 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home