Philip Johnson (1906–2005) was not a great architect. But through wealth, wit and, occasionally, good taste, he became arguably the most influential American architect of the 20th century. He was also simultaneously the most admired and most detested architect of the modern age. Charming but catty, he was a mostly unoriginal designer with a genius for stealing other people’s ideas, yet also a generous promotor of younger pretenders. He was a one-time fascist most at home in liberal New York society, a former anti-Semite who later propelled the careers of Jewish architects, and the world’s first great curator of architecture. He was a gay man who found his greatest success in America’s buttoned-up post-war corporate milieu. He could be ruthless as well as generous, he could be laugh-out-loud funny and then say things that would make you wince. But most of all he was never boring. Apart from, that is, where some of his buildings are concerned, which could be excruciatingly dull.

Johnson was born in Cleveland, Ohio. His father was a big-shot lawyer, his mother from an established wealthy family. His childhood and youth were unremarkable. At Harvard he studied Greek, philology and philosophy; he left his professors unimpressed, and his personal life was marked by depression. It was on travelling around Europe that he discovered his real passion, architecture – in particular the nascent 1920s modernism of Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier and J.J.P. Oud. He was smitten by the purity of the forms, though less so with the social mission.

Johnson was born in Cleveland, Ohio. His father was a big-shot lawyer, his mother from an established wealthy family. His childhood and youth were unremarkable. At Harvard he studied Greek, philology and philosophy; he left his professors unimpressed, and his personal life was marked by depression. It was on travelling around Europe that he discovered his real passion, architecture – in particular the nascent 1920s modernism of Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier and J.J.P. Oud. He was smitten by the purity of the forms, though less so with the social mission.

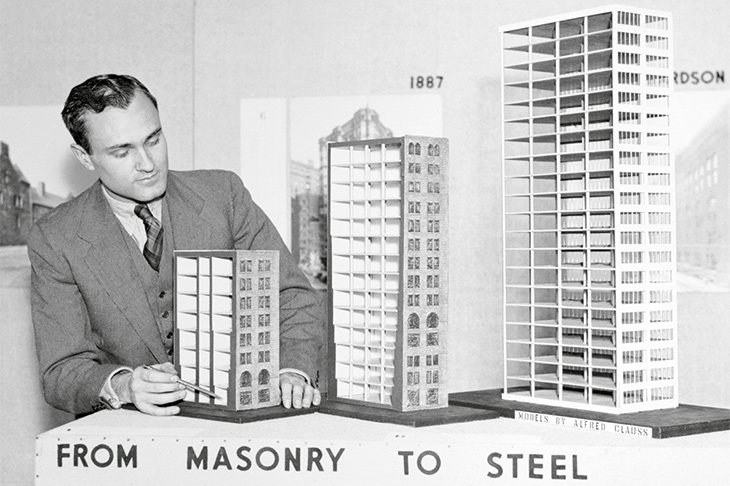

Back in the United States Johnson became the architecture curator of the brand-new Museum of Modern Art in New York, and would go on to play a profound role in shaping the whole institution for the rest of the century, donating some of its finest artworks as well as defining its physical structure. His inaugural exhibition of 1932, ‘Modern Architecture: International Exhibition’ effectively introduced European modernism to the US and changed the course of design. A subsequent show on industrial design laid the groundwork for the subject to be taken seriously by museums.

Only after this would Johnson go on to study for the profession and develop his highly successful career. But there was a gap. In the 1930s Johnson was seduced by fascism, developing a deep admiration for Mussolini’s Italy and an even bigger hard-on for Hitler’s jackbooted Germany, even finding himself enthusiastically reporting for a far-right US magazine as war broke out and German forces stormed through Poland. He latched on to the coat-tails of Father Coughlin, the American Catholic demagogue, designing a tribune from which the priest could broadcast his right-wing message. As Mark Lamster suggests in this excellent new biography, Johnson tried to become an advisor to that other fascist demagogue, Huey Long, and almost certainly harboured ambitions to lead some kind of US fascist movement himself. Johnson’s political career was a farce, ending in complete failure. Yet he somehow managed not only to survive the episode, but to shrug it off as a kind of youthful infatuation.

The Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, designed by Philip Johnson and completed in 1949. Photo: Eirik Johnson

There are, it turns out, second acts in American lives. After serving in the military, Johnson studied architecture at Harvard, where, as architecture curator at MoMA, he was regarded with suspicion by staff but revered by fellow students. He switched his obsession from Nazis to the modernism of Mies van der Rohe, the one-time director of the Bauhaus and now head of architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology. To Van der Rohe’s chagrin it was Johnson who completed the first Miesian house in the United States – a garden room on his Connecticut estate in 1949, the Glass House of the book’s title. Van der Rohe didn’t finish his glass Farnsworth House until 1951, and then had the problem of a client who never liked it.

Johnson made amends by fixing it so that Van der Rohe got the commission to design the Seagram Building on New York’s Park Avenue – a super-refined minimalist tower set back from the street in a plaza that became the much-imitated model for mid-century corporate architecture. Johnson worked on the designs with Van der Rohe, set up his office in the building and was responsible for the Four Seasons restaurant, which he made his own. He would dine there every day, effectively inventing the power lunch, sweet-talking contacts and making and breaking careers. He commissioned Mark Rothko to decorate the room, but the artist, increasingly disgusted by the idea of creating a backdrop for dining bankers and brokers, reneged on the deal. The paintings are in Tate Modern today.

From there, Johnson was rehabilitated, becoming corporate America’s most successful architect. Lamster tells his story deftly, never skimming over awkward details, although Johnson’s famous charm has proven tricky to translate. But why, we are still left wondering, did this architect of relatively little talent but endless social capital become so successful? Lamster, architecture critic of the Dallas Morning News, seems to warm to Johnson’s work, pointing out its elegance with delicacy and wit where he finds it, not always entirely convincingly. 550 Madison Avenue, for instance, might well be a masterpiece of postmodernism, but it is difficult to love, an architectural model realised at 1:1 scale rather than a real work of engaged urbanism. Its stone arcade was always dark and dreary, its interior a failure; only its split-pediment top survives as a light visual gag. Its importance was that it signalled the end of postmodernism as an inventive avant-garde moment and the beginning of its wholesale adoption by big business.

Just as Johnson promoted European modernism in the 1930s, he also gave a helping hand in later decades to Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry (apparently weeping when he first saw the latter’s Guggenheim Bilbao), almost single-handedly inventing the idea of the ‘starchitect’, which has both helped and hobbled architecture in the modern age. While the idea of starchitecture reinforces a myth of the lone creative genius with its monstrous ego (architecture is nothing if not collaborative), it strips the practice of social purpose, reducing it to a single sketch, an expression of individual creativity. Ultimately, that is Johnson’s legacy. Just as he tried to leave social housing and Bauhaus politics out of his early MoMA show and to tone down the socialism of modernism for a US audience, he succeeded in raising the profile of architecture while simultaneously debasing it as a plaything of corporations and the wealthy. Lamster is clear-eyed about this legacy and justly critical. His readable, meticulously researched book spans the history of modernism in the United States, illuminating Johnson’s part in many of its successes – and its failures.

The Man in the Glass House: Philip Johnson, Architect of the Modern Century by Mark Lamster is published by Little, Brown.

From the April 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home