From the April 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

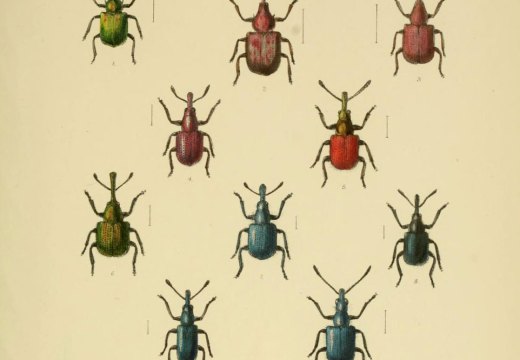

John James Audubon’s The Birds of America, begun in 1826 and completed 12 years later, comprising 435 huge colour plates of more than a thousand birds, many life-sized, is one of the most ambitious projects in publishing history. In this wonderfully mounted and curated show, the National Museum of Scotland presents 46 original unbound prints from its collections, never exhibited before, as well as a rare example of a bound copy of the work, engravings by Audubon’s rivals, taxidermy – some of the birds from Audubon’s own collections – and even examples of the elaborately feathered ladies’ hats that almost caused the demise of the snowy egret.

Born in Haiti in 1785, his childhood spent largely in France, Audubon led a charmed and relatively peaceful American life, in so far as he managed to spend the whole of it between the end of the Revolution and the start of the Civil War. A slave owner and proponent of slavery, he could nevertheless exhibit compassion in his writings – though often more towards animals than people. In describing the purple martins with which he was much taken, he observes that it was the custom of slaves to make houses for them from hollowed-out gourds. He then wonders idly if the slaves ever envied these little birds their freedom. Thanks for nothing, bub.

Print depicting Barn Owls (1827-38), John James Audubon. © National Museums Scotland

He was a rather tricky person. In America he was accused more than once of show-boating and of various technical inaccuracies which didn’t please the scientific establishment. True, he was not an academic, but he was an immensely talented and meticulous field naturalist with years of experience and drawing skill. Some of the professors were just out to ‘get’ him. He won earlier and greater acclaim in Britain and Europe, where gifted amateurs were still celebrated. He impressed the Royal Society of Edinburgh with his prints in 1827, and Edinburgh University was one of the first subscribers to The Birds of America. ‘Until I reached Edinburgh,’ he said, ‘I despaired of success.’

Audubon’s bird prints are both scientific and artistic triumphs. Unhappy with the flat, lifeless look of ornithological illustration at the time, he devised ways of suspending his specimens from wires, painstakingly recreating the flight silhouettes he had observed in the field. The birds’ eyes glisten with intensity and intelligence, as they engage in both daily activities and derring-do. The plates were engraved in aquatint and hand-painted by an army of 50 colourists – a pre-Henry Ford production line.

Concerned with realism and accuracy, Audubon was not above adding a little oomph to his pictures. In images like stills from horror movies, the skulls, eyes and wriggling bodies of hapless victims are pierced by beaks and talons. Audubon had studied in Paris with the painter Jacques-Louis David, and with these birds, there is sometimes a feeling of Marat drooping in his bath. These are narrative paintings. Speaking of his illustration of two great-footed hawks, who are devouring two unlucky ducks they’ve caught, he wrote: ‘Look at these two pirates devouring their déjeuner à la fourchette, as it were, congratulating each other on the savouriness of the food in their grasp.’

Print depicting a Swallow Tailed Hawk (1827-38), John James Audubon. © National Museums Scotland

One of the many joys in this show is discovering Audubon as a writer. In the Ornithological Biography, a separately published companion text to the plates, he describes the traumatic experience of having a beautiful golden eagle that he kept alive for some time in order to observe it. He fell in love with this bird but failed to find a way out of killing it. The experience severely shook him: ‘I […] worked so constantly at the drawing, that it nearly cost me my life. I was suddenly seized with a spasmodic affection, that […] completely prostrated me […] the drawing of this Eagle took me fourteen days.’ It was traumatic for the eagle too.

More to his credit, Audubon presciently railed against depredations into the natural world, which in the mid 19th century were already atrocious. He warned of the voracious destruction of the American forests and its effects on fragile species. ‘Nature is perishing,’ he wrote in 1833. But he wasn’t infallible – there were so many passenger pigeons in North America that he reckoned nobody could shoot them all, not in a thousand years. In fact, 50 years after his death, they were gone. (In the last 10 years, the United States has lost nearly a third of its bird population.)

A bird enthusiast in all senses, Audubon shot thousands more than he ever needed for study. And he enjoyed eating them. He loved the beautiful song of the Louisiana water thrush. And – yum. Apparently. He loved being outdoors, loved what he believed was the complexity, ingenuity and synergy of nature. He particularly praised the American wild turkey, for its beauty, usefulness and intelligence, and probably fell to eating quite a number of them – he liked a good barbecue.

He eloquently defended the cruelly maligned crow, to which are attributed crimes it is physically incapable of committing: ‘The state of anxiety, I may say of terror, in which he is constantly kept, would be enough to spoil the temper of any creature.’ And ‘almost every person has an antipathy to him, and scarcely one of his race would be left in the land, did he not employ all of his ingenuity, and take advantage of all his experience, in counteracting the evil machinations of his enemies.’ The plate of the American crow in The Birds of America shows him perched on a branch in a scholar’s stoop, the feathers glistening like obsidian, the eye very wise, with almost the suggestion of a smile.

From the April 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home