From the March 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Has there been a more idyllic art school than the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing? Set up in 1937 opposite a pub in Dedham, Essex, the school was run according to an egalitarian credo – ‘We do not believe there are artists and students; there are degrees of proficiency,’ ran a line in the prospectus – that reflected the personalities of its two founders, the artists and bon viveurs Cedric Morris (1889–1982) and Arthur Lett-Haines (1894–1978). Morris and ‘Lett’ had been a couple since first meeting in London in 1918. Handsome and raffish, in the 1920s they mixed with the avant-gardists in Cornwall and Paris. By the 1930s, tired of the ‘social whirl’, they bought a farmhouse in Suffolk. Morris worked at the garden and kept a small menagerie of animals, including a tame jackdaw, a cockatoo and a peacock named Ptolemy.

While hard work was prized above all at the school, the only thing Morris and Lett taught with any rigour was canvas preparation. Supervised drawing from classical sculpture, standard in art schools of the time, was abhorred. Students would be sent on field trips, in order to observe directly from nature, or allowed to paint life models in the studio, with Morris and Lett offering (often contradictory) advice at the end of the day. Then students and teachers alike would retire to the pub. At the beginning there were fancy-dress parties almost every weekend.

Portrait of Cedric Morris (Man with Macaw) (c. 1930), Frances Hodgkins. Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne

The likeliest explanation for the fire that destroyed the first school building in 1939 was that Lucian Freud, who had joined earlier that year, tossed a cigarette end into a pile of turpentine-soaked rags one evening before walking into the pub. Precocious and ungovernable, Freud responded well to the laissez-faire methods of Morris and Lett. ‘He didn’t say much, but he let me watch him at work,’ Freud said of Morris. ‘Cedric taught me to paint and more importantly keep at it.’ As the school burned, the painter and arch-traditionalist Alfred Munnings, who lived nearby, happened to drive past. ‘Look what happens to modern art!’ he crowed through the open window of his car.

That winter, a new home for the school was found not far away from Dedham at Benton End, a part-16th-century farmhouse just outside the town of Hadleigh. There were seven bedrooms and students were allowed to live in. The atmosphere was intense and invigorating. Maggi Hambling became a student in 1960. ‘Part of the attraction for me aged 15 was that it was called the artists’ house and notorious for every vice under the sun,’ she recalled in an interview in 2017 (see also January 2021 issue of Apollo). Nearly three acres of garden allowed Morris to exercise fully his passion for botany. Lett, using ingredients from the garden, prepared the food for shared mealtimes, drinking heavily as he went; he was a formidable cook and swapped recipes with Elizabeth David, a regular visitor.

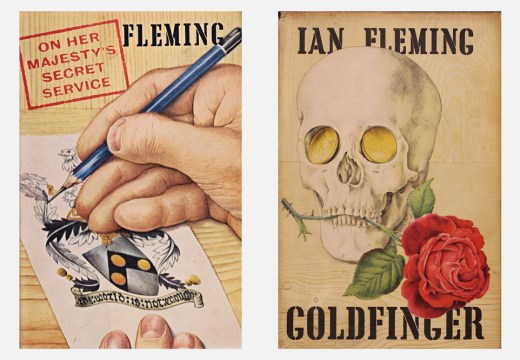

What of the art? Alfred Munnings may have found it threateningly modern, but on the evidence of ‘Life with Art: Benton End and the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing’, most of it lay safely within the English figurative tradition: modest in scale, lyrical in execution and homely in subject matter. The exhibition is the first to bring together an array of work by Morris, Lett and around 20 of their students and friends, including Hambling, Richard Chopping (famous for his James Bond book jackets; see September 2021 issue of Apollo), Denis Wirth-Miller, Frances Hodgkins, Joan Warburton and David Carr. There is a small portrait by Freud. Views of the school itself dominate the first room, including a series of watercolours by John Bensusan-Butt that are almost Japanese in their delicacy – which makes sense given his connection to Impressionism through Lucien Pissarro, who was his uncle by marriage. There are three views of the building in Dedham after the fire in 1939, painted by Warburton, Morris and Carr. Almost identical, they show the extent to which Morris’s students emulated his naive style.

Cabbage (1956), Cedric Morris. Garden Museum, London

Plant and animal life, unsurprisingly, features heavily. In Cabbage (1956), Morris fills almost the entire canvas with thick cabbage leaves painted in varying shades of green, while the plant’s centre glows a promiscuous purple. Only Morris would think to make a cabbage erotic. The heavily cracked Woodpeckers (1936) is shown publicly here for the first time. Joan Warburton’s twilit Peruvian Daffodils, painted a year after Morris’s death in 1982, feels elegiac. Lucy Harwood’s botanical studies are less successful, but three chunkily executed oil portraits, including one of fellow student Glyn Morgan, are deservedly given a wall to themselves. Lett’s more abstract, Surrealist-inspired work gets a fair showing, too; controlled and intricate, mostly executed in pen and watercolour, it contrasts with Morris’s flamboyant oils. There are portraits by Morris – most strikingly of Denise Broadley, one of their first students – and of him, too: in the garden, painted by Morgan in 1957; with his macaw, by Hodgkins in around 1930; and looking distinguished in a pencil drawing by Lett from 1923.

As for Lett, two touching portraits by Hambling from 1975, a few years before he died, show him sleeping, one hand curled over the covers. These are intimate pictures: the two must have been close for her to have drawn him while he slept. In one, a large oil painting, it is clear that he is still fully dressed. Throughout the school’s existence, Lett worked tirelessly on its behalf, acting not only as cook but also as general factotum. Even if, by 1975, the school had essentially been wound down, here is a picture of a man too tired even to remove his sandals before he gets into bed.

‘Life with Art’ is an unusually context-free exhibition. An introductory panel sets the scene, but no further information is provided about either the artists or the school. Some richness is undoubtedly lost with this decision. The dates are unreliable: Carr’s picture of the school building after the fire is unlikely to have been painted in c. 1900. But then, this is not intended to be a white-cube kind of show. The exhibition’s five rooms are painted in rich colours that evoke the vibrancy of life at Benton End. Easels loaded with paper and pencils stand about the place so that visitors can create their own drawings then pin them into frames marked on the walls. It is all designed to express the inclusivity of Benton End itself, where Morris and Lett sought to ‘decrease the division between the creative artist and the public’ (another line from the prospectus). In that sense it’s a fitting tribute to the iconoclasm and verve of the school’s founders.

‘Life with Art: Benton End and the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing’ is at Firstsite, Colchester, until 18 April.

From the March 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?