The architectural historian Mark Girouard had equivocal feelings about researching his book The English Town: A History of Urban Life (1990). He appreciated that it had given him the opportunity to make the case that the Victorian cityscape, long denigrated as an unforgivable hodgepodge of pestilent slums, gloomy factories and pompous town halls, was in fact as worthy of celebration as the medieval and Georgian townscapes that had preceded it. The pain of writing the book came when visiting the towns as they now were, and he could see nothing but catastrophe in the changes that had befallen city centres during the post-war period:

I came to know too well the boa-constrictor hug of the ring road; the cracked concrete, puddles and pornographic scribbles of the subways; the light standards rising out of tasteful landscaping on the roundabouts; the new telephone exchange pushing up its ugly head, with such inspired accuracy, exactly where it could do the most damage; the claustrophobic arcades, streaked surfaces and tattering glitziness of once-new shopping centres.

This is a punchy paragraph, but there is something about the litany of derisory epithets that should alert us to similarities with the language that has always been used to malign the architecture of the recent past. Its fervour certainly recalls that of the master of the architectural take-down, John Ruskin, who directed his ire against such now-loved things as Edinburgh New Town or St Martin-in-the-Fields. Such linguistic echoes reveal that architectural taste is generationally cyclical, and suggest that blanket condemnations of ‘concrete monstrosities’ will eventually give way to a recognition of what was good in post-war architecture.

A change of heart is inevitable, but it will come too late for many of the finest buildings and civic set pieces of the period. In the UK, an assault is taking place on the post-war built environment as far reaching and devastating as that of the post-war period’s erasure of the Victorian city. We will come to regard the demolition of buildings such as Alison and Peter Smithson’s Robin Hood Gardens and John Madin’s Birmingham Central Library with the same bewildered regret as we do the loss of the Euston Arch. Although it is the demolition of individual monuments by famous architects that makes the news, perhaps a more insidious loss is the steady chipping away at the urban fabric of the planned architectural set pieces of the period. Chief among these is the city centre of Coventry in the West Midlands. Sheffield, Glasgow or Liverpool may have more individual modern masterpieces, but Coventry is one of the few places outside the new towns where the post-war architectural imagination was given full reign to create a total urban ensemble.

The freedom to remake Coventry on pioneering modern lines was forged in the aftermath of the events of the night of 14 November 1940, when much of the centre was reduced to rubble by German bombers. Coventry’s response to this catastrophe is central to why I find its post-war built environment so moving. It is sometimes asked why the Second World War did not give rise to monuments to compete with the powerful, sombre classicism of Edwin Lutyens’s Thiepval Memorial, but Coventry, spreading out from the cathedral rebuilt by Basil Spence, is in many ways a city-wide memorial: the whole place is imbued with the values of internationalism, reconciliation and rebirth. I often lead visitors around central Coventry, including people who expected not to like it, and they are always charmed by its combination of picturesque vistas, its superb collection of integrated public murals and sculpture, and its exceptionally considered townscape – created through a strict design code, good materials and street furniture, and quality architectural lettering. Above all visitors are struck by the vestiges of post-war optimism that suffuse the place, even if it is now eroded and neglected.

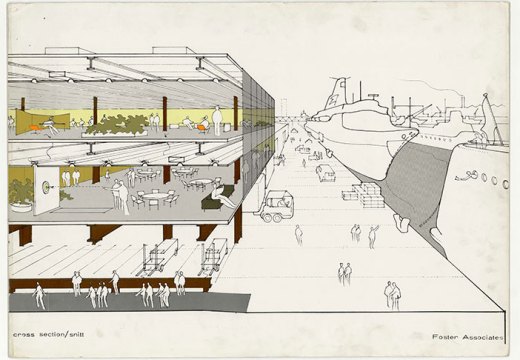

The central baths, Coventry, built by the city’s Architect’s Department in 1962–66 (photographed in 1966). Photo: Bill Toomey/Architectural Press Archive/RIBA Collections

In its day Coventry’s replanned centre was internationally lauded. Coventry was the archetypal post-war boom town, largely based on a flourishing automotive and engineering industry. Sociologists flocked there in order to study its newly affluent workforce. As Britain’s Detroit, it was inevitable that the city’s replanning would be dominated by the car, albeit with an infrastructure that ingeniously segregated pedestrians and vehicles. The reversal of Coventry’s economic fortunes, as deindustrialisation began to bite, was subsequently experienced with particular harshness. Released in 1981, the song ‘Ghost Town’ (1981), by the Coventry-based band The Specials, expressed the sense of urban crisis in Thatcher’s Britain, which they juxtaposed with a romanticised past of the ‘good old days […] inna de boomtown’. This fraught history helps to explain why the dashed optimism expressed in Coventry’s rebuilding became so difficult to stomach, and why the city has become embarrassed to the point of self-loathing by its post-war heritage, trying to force its humane and civic city centre into the mould of a mundane retail park. The nadir came with the building of the postmodern Cathedral Lanes Shopping Centre in 1990, which wantonly destroys the carefully modulated vista set up between the pedestrian shopping precinct and the cathedral.

Those of us who love Coventry had hoped that this drawn-out architectural hara-kiri was coming to an end: the city now has impassioned champions, among them the writers Owen Hatherley and Jones the Planner, while in 2016 Historic England released an impressive report, Coventry: The Making of a Modern City 1939–73, which was followed by a number of significant listings. Then Coventry was made UK City of Culture for 2021. Here was a tremendous opportunity to embrace the city’s unique identity, making a tourist asset of its internationally significant urban planning and the moving story of its re-emergence from war.

Depressingly the city seems intent on continuing to rely on an outmoded retail-led regeneration strategy, although it is difficult to imagine Coventry ever being able to compete with neighbouring Birmingham as an ersatz shopping destination, especially in the current climate. It is grotesque that a city supposedly gearing up to celebrate its culture on an international stage is simultaneously pushing through plans to mutilate listed buildings, including the train station, civic centre, and central baths and leisure centre, all superb instances of the refined and elegant modernism practised by the city’s Architect’s Department after the war. Huge chunks of the south of the city are set to be cleared for yet more banal retail space. The Bull Yard, an urbane square in the tougher idiom of the 1960s, is one thing set to go, despite its being elegantly detailed and home to a wonderful Aztec-inspired frieze, in seemingly kinetic concrete, by the late William Mitchell. For its year of culture Coventry should work with the grain of what it has. Taste will change. With a more sympathetic approach, Coventry might aspire in a few decades to become a World Heritage Site, emulating places such as Bath or Ironbridge – because it too is a supremely eloquent exemplar of a particular moment in urban history. The city will regret the carelessness with which it is trashing what makes it unique.

From the September 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?