From the December 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

At ‘Top Secret’, the Cinémathèque française’s show about spying and cinema (until 21 May 2023), I feel as if I have walked into a scene from The Conversation (1974), with the soundtrack cranked up to an uncomfortable level. Resonating throughout the space is a drone-like noise, much like the one Gene Hackman in Francis Ford Coppola’s Cold War classic hears in between the clicks and voices of an illicit recording he is listening to on a loop. Hearing the sound reverberate around me, I’m impressed by the lengths to which the curators have gone to simulate the experience of surveillance. Then, as I develop a headache, it dawns on me that perhaps something else is going on. A guard laughs, putting me right: there is a defective loud speaker somewhere, and for the rest of my visit I have the drone for company and a man with a ladder checking all the electric sockets.

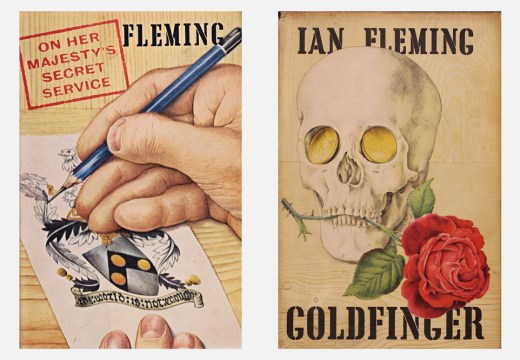

Unpleasant as it is, I’m glad to experience the exhibition in these conditions. The space on an upper floor of the Cinémathèque is densely packed, opening with an impressive collection of early technology designed to collect intelligence, spying or surveillance. Among the exhibits here is the Enigma machine, the cipher device used by the Germans to encrypt messages that Alan Turing and his team in Bletchley Park cracked in the Second World War. In the other rooms are film posters, costumes, movie clips, photos and various pieces of memorabilia from real acts of espionage, including the exploding rat used by Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE); also from films, the most familiar being a selection of James Bond gadgets. It’s strange, even a little sad, to see them as isolated objects under glass without Bond or Q to play with them.

The show is divided into several small rooms connected by temporary walls, creating back-alley-style corridors that make visitors wander around as if caught in a maze. The material is organised thematically, with a distinct subject for each room, but also proceeds chronologically. This is not a carefree show encouraging escapism alone. Reality is always around the corner, often quite literally. Along one set of small corridors for example, we are presented with photos, both real and by artists, from Stasi-surveilled East Germany. This presence of real-world politics is no surprise in a show involving spying, but the exhibition makes a point of underscoring the role of technology in espionage and cinema. The curators establish the link in the first room, which is dedicated to early intelligence devices. ‘Like a spy,’ they say, ‘film-makers use low-tech or cutting-edge technology to record or tamper with the reality to tell a story’.

While the show encourages us to reflect on the relationship between humans and the state, and the limits placed on our freedom, this doesn’t mean we can’t enjoy the simple story of how spying has appeared on screen. This narrative takes us from the silent era into the heyday of femmes fatales, such as Hedy Lamarr, who played many spies on screen and also pioneered technology that would form the basis of today’s WiFi, GPS and Bluetooth. Mata Hari features prominently, too, with photographs and documentation presenting her activities as a double agent who would be executed by a French firing squad. Alongside this are examples of the many incarnations she inspired, played by everyone from Greta Garbo to Sylvia Kristel.

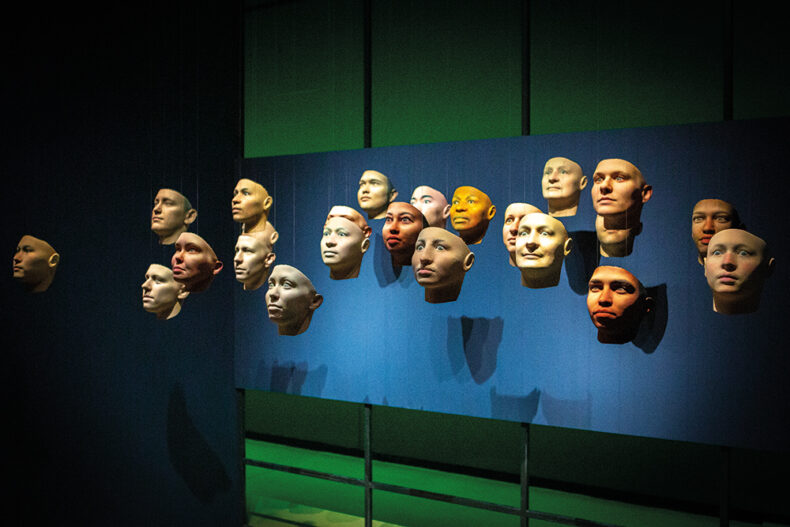

Installation view of Probably Chelsea (2017) by Heather Dewey-Hagborg and Chelsea Manning at the Cinémathèque française in Paris. Courtesy Cinémathèque française

The work of Alfred Hitchcock and Fritz Lang take us through the 1930s to the ’50s. With the 1960s, we enter the era of James Bond, who is joined by his onscreen successors, from Austin Powers to Jason Bourne. It is with the latter franchise spanning five films in the 2000s–2010s that we see the shift to spies as tech geeks, and what the curators call ‘citizen spies’. Today, via modern computers and phones, the act of spying and going dark to escape state surveillance has been made all the more possible, the curators explain, and this has given rise not only to the Bourne films, but also classic TV series such as Le Bureau des légendes, starring Mathieu Kassovitz.

The final rooms are as disturbing as the previous ones are escapist, demonstrating how citizens have stood up to state surveillance, risking if not their lives, then certainly their freedom and anonymity. Here we find the whistle-blowers Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning. Also featured are drones and footage of targeted state attacks such as the raid that killed Osama Bin Laden in Pakistan, as reimagined by artists. The exhibits in these rooms range from avant-garde, with work by Harun Farocki, among others, to popular, with Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty (2012).

The most arresting exhibit is Probably Chelsea (2017), a curious work by Heather Dewey-Hagborg and Chelsea Manning. The installation comprises several very realistic masks, made from 3D prints based on the result of Manning’s DNA being fed into an algorithmic model. The faces are all doing something different – eyes looking upwards or straight on, traces of a smile or completely serious. They are hung from the ceiling, seemingly floating in space, like puppets just about to speak, and they make dove-like shadows on the ground.

Manning’s massive disclosure of classified government documents on US army operations in Baghdad, Afghanistan and elsewhere led to her spending seven years in prison; she was released in 2017. She has certainly become an emblematic figure, both as a whistle-blower and representative of the major social shift in the last decades over gender identity and the breaking of binary male/female categories. The Probably Chelsea portraits are meant to evoke the fluid nature of identity and the battle to box Manning into a single one, even after she has come out as a trans woman. The relevance of all this to cinema, however, is tenuous. It’s not entirely the fault of the show as we are still at the early stages of understanding how modern forms of surveillance and spying will translate on screen.

‘Top Secret: Cinéma et espionnage’ is at the Cinémathèque française, Paris, until 21 May 2023.

From the December 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home