Bajan riñendo, (They descend quarrelling), from the ‘Witches and Old Women’ Album (D), page 1 (c. 1819–23), Francisco de Goya. Photography by Alex Jamison

In 1793, when he was 46 and a successful painter at the Spanish court, Francisco Goya suffered a severe illness which left him profoundly deaf. While convalescing, he began to paint small pictures for private collectors, partly to recover his medical expenses and partly to regain his confidence and that of his patrons. He also began to make drawings in the first of what would become a series of eight private albums. These many drawings in brush and grey wash, occasionally retouched with pen and ink, accomplished between 1793 and his death in 1828, were uncommissioned work, shown only to friends, and full of a sometimes gleeful, sometimes savage subversive energy – by turns erotic, satirical or humorous. They were made alongside his official portraits and religious paintings and his groundbreaking series of etchings, including Los Caprichos, of 1799, and Los desastres de la guerra, 1810–1820. And while they share with the prints certain themes and preoccupations, the drawings have their own charged and delicate immediacy. Many had titles written in ink, and page numbers, indicating within each album a progression of ideas.

After his death, however, Goya’s drawings were dispersed, and all sense of order and chronology was lost. New collections were formed, generating alternative relationships between the drawings, far from the original logic of their creation. Over the last 50 years there have been different attempts to reorder the scattered sheets. In this exhibition, the Courtauld has been inspired to reconstruct the least known of Goya’s albums, the so called ‘Witches and old women’ album, known to scholars as Album D, which is full of bizarre and bitter images, conjured from his subconscious with deft conviction. Gathering together all 22 surviving drawings from 16 museums and several private collections, the Courtauld has managed once again to combine scholarship with an absorbing and comprehensible display.

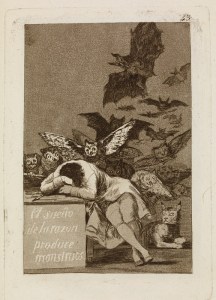

The lower exhibition room provides context, led by the famous print which became number 43 of Los Caprichos – The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. The display follows the evolution of the monsters of Goya’s imagination, from the early drawings created soon after his illness in Album B, where a double-sided sheet reveals a brothel scene and a company of pompous, smartly dressed asses, through to the prints of Los Caprichos, where social satire gives way to a dark world of witches and nightmares. In Los Caprichos number 56, To Rise and Fall (1797–98), a satyr with giant head holds a bare-legged male figure, otherwise dressed in an elegant jacket, who holds fire in his hands. The satyr sits upon another figure, while a third falls behind into the distance, towards the globe they are all balanced upon. The upright figure, the catalogue suggests, may represent the Queen’s lover, Manuel Godoy who rose – playing with fire – to be Prime Minister but was toppled from power by intrigue in 1797. Alongside, three hideous old women (possibly procuresses or witches) spin, like the Three Fates, while a bundle of babies hangs tied up in the air behind them.

Album D followed 20 years later, with a conjectured date for these drawings of 1819–1823. This is the period of Goya’s renowned ‘Black’ paintings, originally created on the walls of his house outside Madrid, which reflect his despair over Spain’s war with Napoleon and the vicious oppression of the Inquisition. Far from being weighed down, however, the first six drawings feature figures tumbling, spinning, rising or falling, or carried in the air; it is as if they are born aloft by Goya’s imagination. His masterful use of light and shade, his indefatigable line, gives these drawings a purposeful energy: comic as the images may be, they have moral intent. And they are raucous with the squawks of monkeys, the shrieks of women, the banging of tambourines and clattering of castanets. There is a kind of joy in his extraordinary facility, which brings these creatures to life, defying our disbelief. These six are then followed by the rest of the drawings, each with a single figure or group of figures set against a plain background, pursuing elusive but related themes. The figures express a wild fury against religious and social hypocrisy, alongside a fear of madness and witchcraft. As arranged by the curators, you see the mood evolve, supported by wonderful sheets from the contemporary Album E, the so-called ‘Black-border’ album.

Sensibly, the details of the admirable scholarship which lies behind the show are kept for the catalogue. In the exhibition itself you are free to marvel at Goya’s genius.

‘Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album’ is at the Courtauld Gallery, London, until 25 May.

Related Articles

12 Days: Highlights of 2015 (Emma Crichton-Miller)

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home