From the September 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘He is a mystic,’ observed Joris-Karl Huysmans of Gustave Moreau (1826–98), ‘locked up in the centre of Paris in a cell to which not even noise of contemporary life can penetrate, though it beats furiously at the gates of the cloister. Rapt in ecstasy, he sees entrancing visions glitter before his eyes, the sanguinary apotheosis of other ages.’ Edgar Degas took a rather more matter-of-fact view of his friend. A mystic? Yes, he acknowledged; but one ‘who knows what time the trains leave’. There is something of this bracing disparity at the heart of Waddesdon’s splendid exhibition of Moreau’s illustrations for the Fables of Jean de La Fontaine (1621–95), in which intense, jewel-like colour and strange, expressive landscapes coexist with the pithy and often worldly advice of the fables. You can do more with kindness than with force, says one. Be happy with what you’ve got, says another; your king might be wicked, but the next may be worse!

The series was begun in 1879 when Moreau, among other artists, was commissioned by the art collector Antony Roux to create illustrations for La Fontaine’s Fables. Between 1879 and 1884 Moreau produced 64 watercolours for Roux. Although nearly half were lost during the Nazi era, the 35 surviving works, mostly not exhibited since 1906 and until now reproduced only in black and white, are currently on show at Waddesdon Manor; all but one, from the Musée Gustave Moreau in Paris, are on loan from a private Rothschild collection. The fables themselves are remarkably varied, deriving from Aesop and other tales from classical antiquity as well as traditional European and Asian stories. Moreau seized the opportunity presented by this diversity not only to experiment with style and handling but also to be playfully referential, introducing his own layers of complexity. Leonardo is present in the coiled hair of Fortune and her rocky landscape background in The Man who runs after Fortune and the Man who waits for it in his Bed; Rembrandt in the shadowy interior of The Miser and the Monkey; Watteau’s fêtes galantes in the elegant folk who stroll about the evening landscape in An Animal in the Moon. Yet for all the visual fun and fireworks, Moreau keeps La Fontaine’s pathos and wit at the heart of his illustrations.

Allegory of Fable (1879), Gustave Moreau. Photo: © Rothschild private collection/Jean-Yves Lacôte

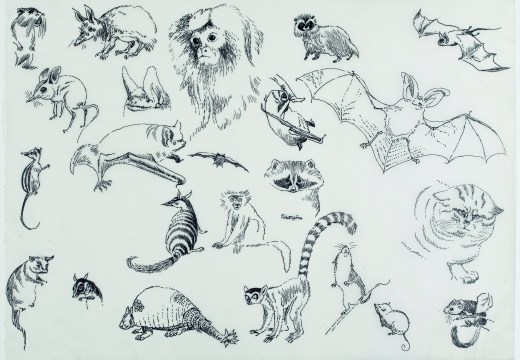

The watercolour that opens the exhibition, and the first Moreau created for Roux, the Allegory of Fable, introduces us to a recognisably Moreau-esque world of myth: Fable, represented by a woman carrying the mask of comedy and the whip of satire, rides nonchalantly through the air on the back of a hippogriff (half horse, half griffin), the hint of a smile on her lips. Ah yes, we seem to be in the familiar territory of Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864), the work that established Moreau’s reputation as a painter of myth and legend, of splendour and mystery. Yet we soon find ourselves in less elevated company as Moreau dives into La Fontaine’s all too human world – albeit one in which creatures perform our follies. Here, for instance, is an illustration of a fable about a dolphin that saves a monkey from a shipwreck, thinking he was a man. The monkey soon gives himself away, whereupon the dolphin tosses him into the sea, deciding to return for a more worthy passenger. Moreau gives us a scene of existential horror unfolding against a bleak, bruise-coloured sky and a moss-green sea; and while the dolphin is pure heraldry, all baroquely bulging crown and flourishing fronds, the screaming monkey is absolutely real, closely based on life studies made in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. It is a contrast that adds distinctly to the unsettling nature of the image.

The Monkey and the Dolphin Photo: © Rothschild private collection/Jean-Yves Lacôte

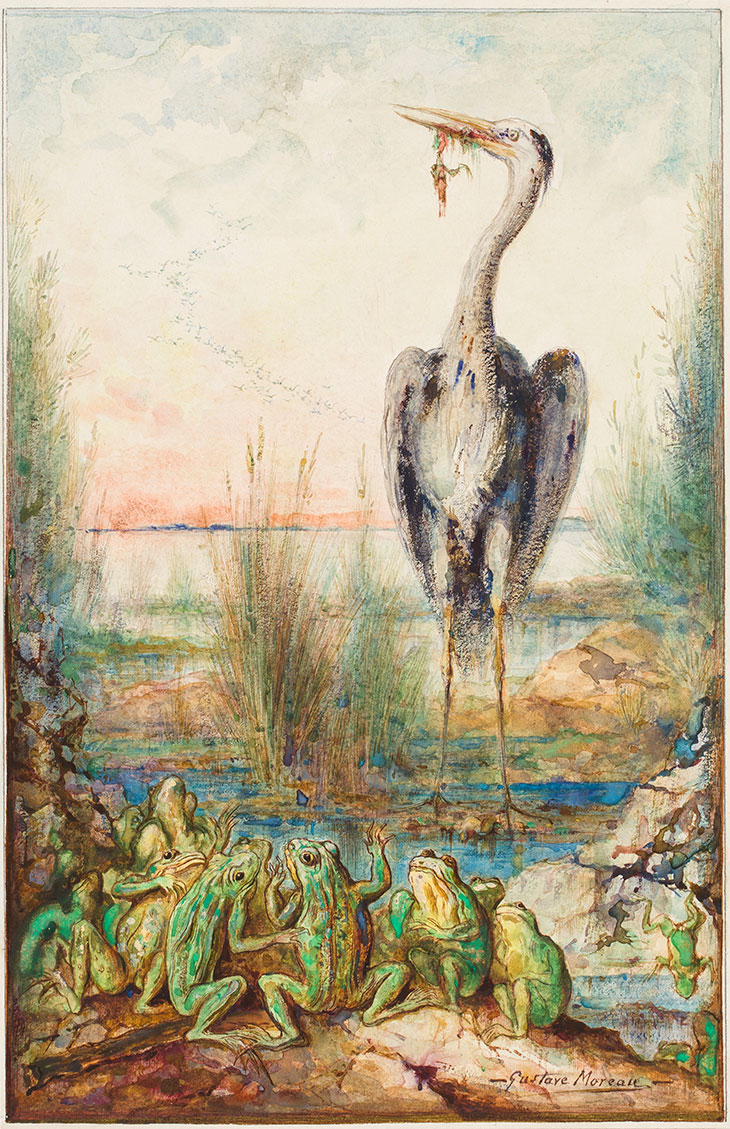

The Frogs who ask for a King – a request that has unfortunate consequences when they are granted a frog-eating heron – is disturbing in a different way. The amphibians that gather in consternation to discuss their predicament are similarly based on sketches from specimens, and here there is no refuge in visual convention. Perhaps because Moreau was not an experienced illustrator of books and magazines, a scene that might be represented by another artist in a comfortable storybook idiom is instead expressed with all the seriousness of a major composition. Like many of the watercolours here, it is more a small-scale picture than an illustration.

The Frogs who ask for a King (1884), Gustave Moreau. Photo: © Rothschild private collection/Jean-Yves Lacôte

Backgrounds play an exceptionally important role; La Fontaine’s rats, cats, foxes, elephants, dragons and humans enact their mordant commentaries on human nature against an extraordinary range of seascapes, landscapes and richly imagined interiors. There is no overarching style that unites the watercolours: Moreau approached each fable on its own terms. One of the final works in the exhibition illustrates a story about a snake’s tail complaining that the head always got to lead. Why could it not be treated equally? The gods consented to its request, and the sightless tail led the snake to the River Styx. In response, Moreau created one of the most mesmerising watercolours of the series: the muscular, tragic snake writhes before a near-abstract landscape of poisonous lapis lazuli waters and soaring rocky towers, fitfully lit by orange flames and obscured by smudgy smoke. Moreau is at his freest in this experiment with the possibilities of watercolour. Expressive brushstrokes almost tip the composition into abstraction as he describes the wild sublimity of the scene; and yet he applies just enough structure to hold the design together. Those train times, you see.

The experience of being in the single, dark-painted exhibition room hung with all 35 watercolours is exhilarating. Because they have been protected from light, the pigments are as vivid today as when the artist laid down his paintbrush. And what pigments they are: a master of colour, Moreau uses gem-like hues with extraordinary richness. One contemporary described his fables as ‘all ablaze with the colours of the prism’, while another imagined him as a jeweller manqué who, ‘drunk on colour, had ground up rubies, sapphires, emeralds, topazes, pearls and mother-of-pearl to make his palette’. To be more prosaic, the object labels are models of elegant contextualisation, each including a discrete summary of the fable in question, and the exhibition’s curator, Juliet Carey, has written a superb accompanying catalogue with excellent illustrations.

‘Gustave Moreau: The Fables’ is at Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire, until 17 October.

From the September 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?