In the summer of 1802 the 27-year-old J.M.W. Turner, recently elected to the Royal Academy, made his first trip abroad. With the ink barely dry on the Treaty of Amiens, he crossed the Channel armed with paints and sketchbooks, a few basic phrases of French and German and some stout walking boots. He passed through Paris, hardly stopping to admire the artistic treasures amassed by Napoleon in the Louvre. It was not that he was uninterested in the art of the masters – he would spend a month in the Louvre on his way back – but he was impatient to reach his destination, the Swiss Alps.

Turner’s choice of destination was unusual. Most British travellers of the period still viewed the Alps as an obstacle in the way of the Grand Tour, but the Romantic discovery of the ‘delightful horror’ of the Sublime had begun to change that perception – and Turner’s imagination had been fired by the wash drawings of Switzerland that John Robert Cozens had made a quarter of a century earlier. Italy, France and the Netherlands were familiar terrain for the landscape painter; Switzerland was a new artistic frontier.

A seasoned traveller, Turner had fallen into the rhythm of spending his summers ‘on the wing’, gathering sketches to be worked up into landscape paintings in his London studio. With the mountains of Wales and the Scottish Highlands already under his belt, he had high hopes of the Alps. He was not disappointed. He would return five times to Switzerland – in 1836 and every year from 1841 to 1844, when he was pushing 70.

The Schöllenen Gorge from the Devil’s Bridge, Pass of St Gotthard (1802), J.M.W. Turner. Photo: © Tate, London, 2019

On that first expedition he took an arduously roundabout route from Geneva via Chamonix to Aosta, then north to Thun and across the Brünig Pass to Lucerne and south to the St Gotthard Pass. Amid the forbidding landscapes of that gruelling itinerary, recorded in dark, brooding images such as The Schöllenen Gorge from the Devil’s Bridge, Pass of St Gotthard (1802), Lucerne with its lake reflecting the mist-wreathed mass of Mount Rigi must have seemed a haven of light and calm. He would return on four of his five subsequent tours, making the lakeside city and its surroundings the subject of more than 30 sketches. Again and again he was drawn back to the challenge of capturing the mountain and its reflection in different lights – at dawn, at dusk or lit by a silvery moon rising through vapour – and from different viewpoints, including the deck of a paddle steamer after a modern ferry service was launched in 1837. But as with Monet’s observations of the Thames from his suite at the Savoy, it was from the windows of the lakeside Schwanen Hotel (now the Schwanen Restaurant) that Turner could most readily record the landscape’s fleeting, subtle changes of mood.

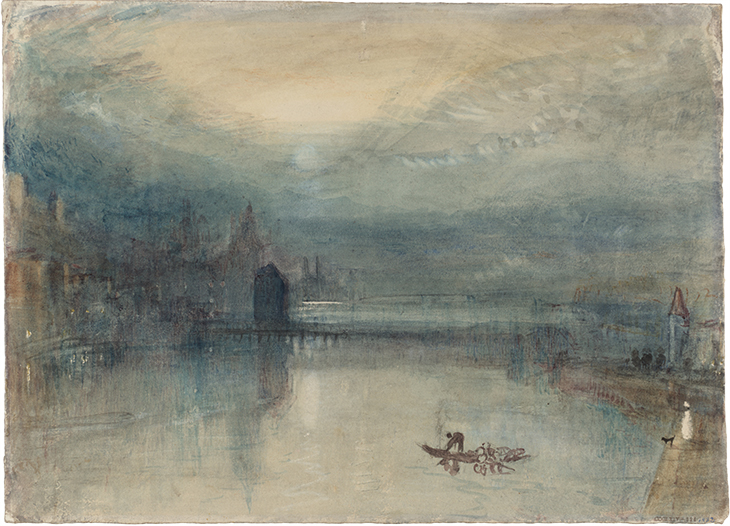

Lucerne by Moonlight: Sample Study (c. 1842–43), J.M.W. Turner. Photo: © Tate, London, 2019

The Chapel Bridge, Lucerne. Photo: Robert Kittel; © Luzern Tourism

The British obsession with the weather may be a cliché, but it’s arguable that we owe our landscape-painting tradition to our fickle climate. Turner suggested as much in a Royal Academy lecture of 1811 when he told students: ‘An endless variety is on our side and opens up a new field of novelty.’ In Switzerland he found novel geology matched by novel meteorology, with every valley boasting its own microclimate. Lucerne gave him all the variety of weather he could wish for, and he recorded its changing effects with remarkable accuracy in paintings such as Lake Lucerne: The Bay of Uri, from above Brunnen (c. 1844). His milky lakeland mists are meteorologically correct: they hold water.

Indeed, this was the official verdict of Switzerland’s Federal Office of Meteorology, when consulted by Fanni Fetzer, director of the Kunstmuseum Luzern, as part of her research for the exhibition ‘Turner: The Sea and the Alps’, which opens at the museum next month (6 July–13 October). Marking the 200th anniversary of the Kunstmuseum and its responsible body, the Lucerne Art Society (Kunstgesellschaft Luzern), the show highlights the artist’s engagement with the sublime through a combination of marine and mountain themes. It is hard to imagine a more suitable setting than the museum’s galleries in the Jean Nouvel-designed Lucerne Culture and Congress Centre, which hugs the shore of Lake Lucerne.

The Lucerne Culture and Congress Centre. Photo: Ivo Scholz; © Switzerland Tourism

British audiences familiar with Turner seascapes – from the dramatic oil Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth (exhibited 1842) to the limpid ‘colour beginnings’ of Margate beach scenes – may be less aware of the extraordinary range of his Alpine landscapes. Alongside imposing canvases such as The Fall of an Avalanche in the Grisons (exhibited 1810) the Lucerne show includes pencil sketches, wash drawings and watercolour ‘sample studies’ designed to encourage patrons to commission paintings.

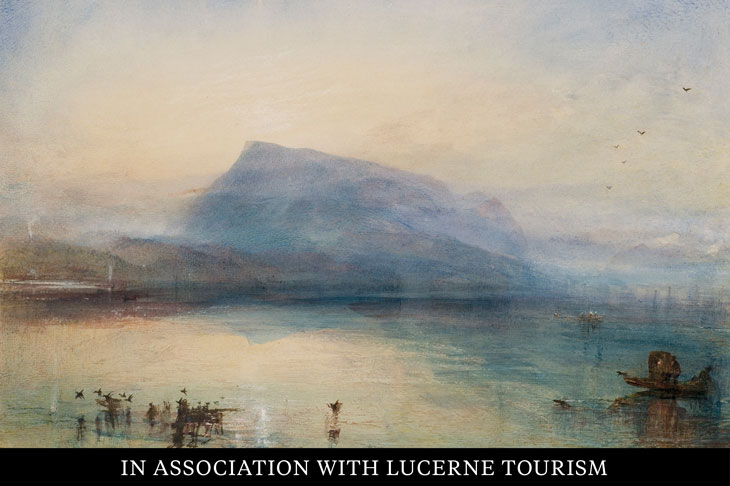

Lucerne with Pilatus beyond (c. 1841–44), J.M.W. Turner. Photo: © Tate, London, 2019

Turner never intended his unfinished watercolours to be shown in public, though after his death his executor John Ruskin took the liberty of including them in an exhibition at Marlborough House, London, in 1857. But The Blue Rigi, Sunrise (1842) – the sample study that became the most expensive watercolour on record when acquired by Tate in 2007 for nearly £5m – was finished for sale. As an exercise in conjuring an impression of distant solidity through diaphanous colour it is unsurpassed; the foreground detail of the flight of startled ducks silhouetted against the silvery surface of the lake only serves to enhance the transcendental mood. As Turner approached old age he entered a meditative phase in which the exploration of light through colour became an almost mystical pursuit. Ruskin caught his hero’s mood in the first volume of Modern Painters (1843) when he wrote: ‘We do not want chalets and three-legged stools, cow-bells and buttermilk. We want the pure and holy hills, treated as a link between heaven and earth.’

Although he began an imaginary Sunset from the Top of the Rigi (c. 1844) in his London studio, Turner never climbed the mountain to admire the view – a bucket-list experience for later tourists. He preferred to contemplate heaven from earth. The Rigi was his Mont Sainte-Victoire, a distant mass of rock on which to test his ability to render illusions of space and form through atmospheric colour. As he told Ruskin in 1844: ‘Atmosphere is my style.’ In Lucerne, he was in his element.

Laura Gascoigne is the art critic of the Tablet and a regular reviewer for the Spectator.

‘Turner: The Sea and the Alps’ is at the Kunstmuseum Luzern from 6 July–13 October (www.kunstmuseumluzern.ch). The Swiss Travel Pass offers unlimited travel on consecutive days via rail, bus and boat on the Swiss Travel System network, and also covers scenic routes and local trams and buses in around 90 towns and cities. It includes the Swiss Museum Pass, which allows free entrance to 500 museums and exhibitions (prices from £178 in second class; rail.myswitzerland.com).

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home