On his death, in 1745, Jonathan Richardson (1667–1745) was hailed by the writer George Vertue as ‘the last of the Eminent old painters that had been cotemporayes in Reputation – Kneller Dahl, Jarvis & Richardson for portrait painting.’ Richardson, the talented son of a London silk weaver, painted prolifically the luminaries of the late Stuart, early Georgian era – including Sir Robert Walpole and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, and his friend, the poet Alexander Pope. Arguably he was as influential in his own time as a teacher, theorist and connoisseur-collector of Old Master drawings. Samuel Johnson credits him with having inspired Joshua Reynolds to paint. This thoughtful exhibition focuses however on another aspect of his fame. In among the more than 1,000 autograph drawings he bequeathed his son, most of them portraits, were a series of self-portrait drawings. Begun around 1728, shortly before Richardson retired from professional life, and pursued at a rate of perhaps one a week or fortnight for the next ten years, these were usually dated, providing a visual record of his changing state of mind and appearance. Of this remarkable exercise in self-scrutiny, today only around 55 drawings are known. For its fourth show in the perfectly formed Gilbert and Ildiko Butler Drawings Gallery, the Courtauld is showing 18 of these self-portraits, complemented by four portraits of his beloved only son, Jonathan Richardson the Younger, whom he dubbed, ‘my other self’.

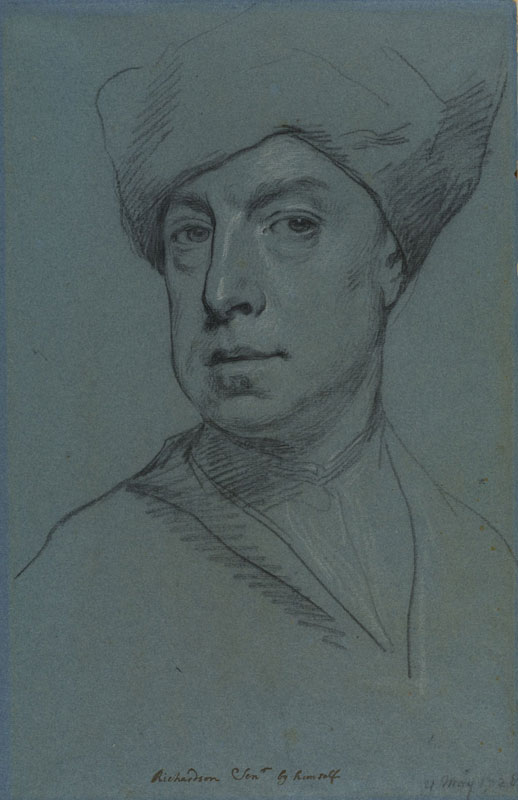

The exhibition begins not at the beginning, but with a series of small portraits executed in graphite on vellum, showing the range of styles and moods in which he captured his own likeness. These intensely private works were not shown to any but an inner circle of friends and family. The medium of graphite on vellum, however, with its potential for more precise delineation and delicacy, allowed for a certain formality. The first image, created in 1730, shows Richardson in his full periwig, bland of face, the curls spilling delicately over his formal clothing. Beside it in a double frame are placed two curiosities: a drawing copied from a now missing painted self-portrait of himself at the age of 25, almost identically periwigged and cravatted but with the tenderly captured soft diffidence of youth (1735); and beneath, one of his last self-portraits from 1736, dated 1st August, where he appears without his wig, in his soft cap, executed with sure, summary lines and rough shading.

The day after he copied his 1692 self-portrait, he wrote a poem about the passing of time entitled, ‘Enjoy the Present’, including the line, ‘Life now is so much shorter than it was’. As the catalogue (now only £1!) makes clear, Richardson’s habit of self-portraiture, charting his declining physical appearance, was married over a decade to a discipline of almost daily poems, where he examined his state of mind. Indeed as interesting as the images themselves is the intellectual and philosophical hinterland they suggest, which drove this self-made man, an admirer of Milton, who apparently turned down royal patronage, to pursue this humanist practice.

A graphite on vellum self-portrait, pretty much as Rembrandt, in fur hat, is evidence of his adulation of this Dutch master. A profile, from 1734, playfully interpreted as a classical bust, as if on a coin, and a self-portrait, face on, from 1732, with his bald head crowned with poet’s laurels, further reveal the cultural milieu he shared with his friends and his classically educated son.

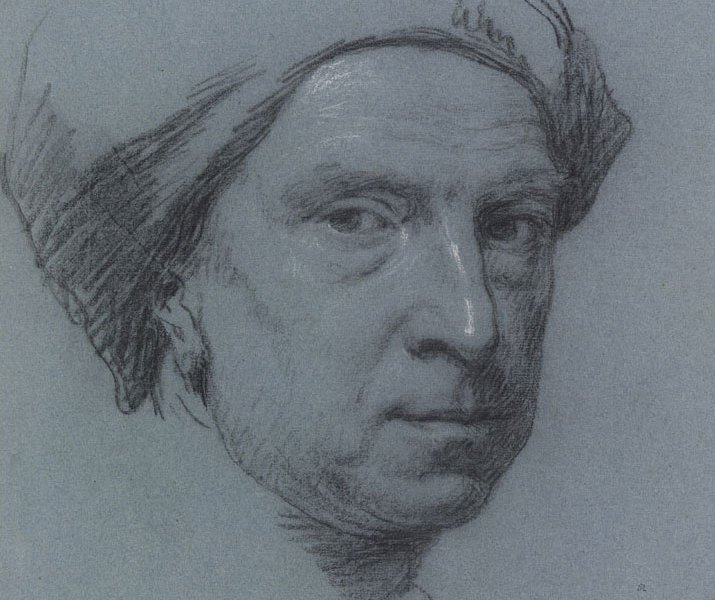

The self-portraits had begun however, in 1728, with a series of large, bold, emphatic chalk drawings on blue paper. These have a startling directness and intensity. It is as if we are merely witnesses to Richardson’s self-searching. The sharp geometries of his cap are set off by the sensitivity of the modelling, with chalk highlights vividly summoning his presence.

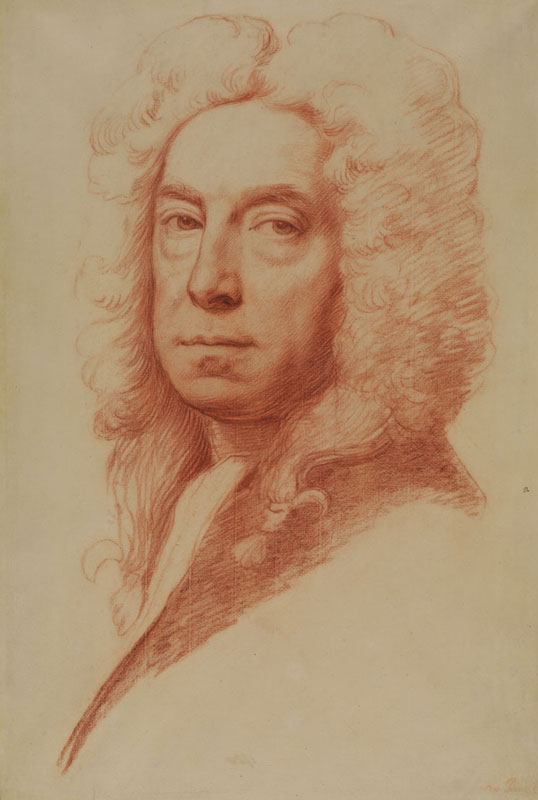

Further works suggest the range of moods in which he confronted his ageing face. A touching example from 1735 shows him with neither cap nor wig, bare-headed, his wrinkles and sagging skin summoned in a softer, more tentative, exploratory manner. By contrast, a large white sheet from 1738, one of the last self-portraits, executed in red chalk, shows him as he might appear in public, his periwig evoked with confident chalk lines, his gaze steady, his chin firm. I was left with many questions – but this is mainly a result of being drawing into such rare intimacy with an artist whose real gift, it turns out, was not for society portraiture but for the subtle exploration of his own soul.

Jonathan Richard By Himself, The Gilbert and Ildiko Butler Drawings Gallery, The Courtauld Gallery, 24 June – 20 September 2015

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home