Despite taking two planes and a three-hour boat ride to get here, when I arrive in the Lofoten Archipelago in the Norwegian Arctic Circle, I find it hard to create a separation between the images I have previously googled, and the real, sublime thing in front of me. As I take pictures on my phone and the landscape reverts to flat surface, I am particularly perplexed when the Northern Lights – starting like clockwork at midnight – are not a gaudy green, but whispery and white, subtly multicoloured like a night-time rainbow, the green a distorting effect of the camera.

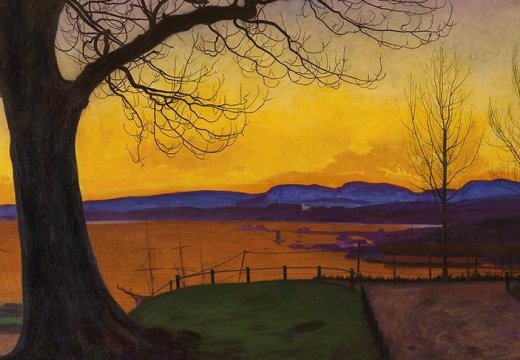

I am not the first to feel this way. ‘Difficult – difficult to paint this! To convey the height, grandeur, and nature’s inexorable, merciless tranquillity and indifference,’ wrote the Norwegian painter, Christian Krohg, on visiting the islands in 1896. ‘What may not be expected in a country of eternal light?’ writes Mary Shelley in Frankenstein, the first three chapters of which are set in the Arctic, a land of ‘perpetual splendour’.

Francesco Urbano Ragazzi (as the curatorial duo Francesco Urbano and Francesco Ragazzi call themselves), have chosen ‘Fantasmagoriana’ for the title of this year’s Lofoten International Art Festival (LIAF). The name comes from the German anthology of ghost stories which inspired Shelley’s Frankenstein. Having lived in Venice, the curators are conscious of how monstrous a machine a contemporary art fair can be, and have instead opted for a ‘sustainable production system’. LIAF is a ‘nomadic’ biennial, in the sense that curators can pick out any location on the islands. The main site for the festival is Kabelvag, the region’s former capital which is currently home to the Nordland School of Arts and Film and where the Dada artist Kurt Schwitters was interned by the Nazis in 1940.

Poupées poubelles (1971–1980), Marianne Berenhaut. Photo: Kjell-Ove Storvik; courtesy the artist and Dvir Gallery

The former courthouse, where dissenters were put on trial during the German Occupation, is the setting for Marianne Berenhaut’s solo show ‘The Adjourned Courtroom’. It features the Belgian artist’s series of Poupées poubelles, mutant doll sculptures made from rubbish. One sculpture consists of a pink corseted dress slumped over a skeletal Carrefour broom; another is made out of stuffed stockings, a colander fleshing out the torso, the whole elongated figure hanging from the courtroom’s cornices. Berenhaut, a Holocaust survivor, creates ghosts that are not ethereal but precisely physical; they look as if they would break if touched, but are nonetheless defiantly here. Urbano Ragazzi say that they wanted to ‘heal the space with her sculptures, to insist on the history but also celebrate the incredible force of those who survived’. In recent years the courtroom has been used as a place of asylum for Syrian and Ukrainian refugees.

Artefacts from the War Museum of neighbouring Svolvaer, also deal with the monsters of modern history. Four watercolours of dwarfs after Disney’s Snow White, supposedly by Adolf Hitler and bought by the museum’s owner, can be seen in the Nordland Cultural Centre. The dictator’s doodles are displayed alongside drawings by Susan Te Kahurangi King, a New Zealand artist who stopped speaking at the age of four. Made when the artist was 12 and featuring Donald Ducks, landscapes of quasi-geological repeated forms and dismembered, falling figures, until recently these subversive works were once regarded merely as childish scribbles.

At the Edge of the Known World (1978-2008), Rimaldas Vikšraitis. Photo: Kjell-Ove Storvik; courtesy LFS Kauno skyrius

Everywhere you look in Lofoten you can see the pyramids of racks used to dry stockfish. Their silhouette on the seashore is particularly gothic in the dark and I learn that the air is filled with the stench of fish during the late winter and early spring. In ‘The Museum of the Sun’, Urbano Ragazzi highlight the existing collection of works by Norwegian artist Kaare Espolin Johnson, who moved to the area in the 1950s. His etchings and serigraphs depict the hardship of life dictated by the tides, with the form of rocks, waves, fishermen and their wives created out of pure black surface. Full of folkloric elements such as trolls, the show suggests links between Espolin’s art, legends of the Sami people and the work of Rimaldas Viksraitis, the Lithuanian photographer whose series At The Edge of the Known World depicts peasant communities in post-Soviet Lithuania. His black-and-white photographs show human and animal bodies in various degrees of pleasure, pain and intoxication. Located in a blue-and-white-painted corner room of the museum looking on to the ocean is an installation by New Mineral Collective. On a plasma TV screen plays Tidal Body, a video and sound piece inspired by the movements of the sea in the archipelago, the austere landscape and the extractive economy it supports. The room includes a vase of bright red roses, alongside a bench of inflatable cushions and a tap, for public use. ‘An open mouth, A horizon of water,’ reads each paper cup.

Maps play an important part in the proceedings. A 19th-century perspectival map by the local artist Kristine Colban Aas shows Lofoten from the nearby Tjeldbergtind summit. (My own experience of seeing the same view on a hike seemed heightened after seeing the map.) In My Favourite Places (2022) Tine Surel Lange, another Lofoten local, creates auditory maps of the area, recording her experiences, history and wildlife of the area as she drives through the landscape. Lange has made the sound files available to download with accompanying routes, so the visitor can take up her place in the driving seat. Meanwhile the South African artist Noland Oswald Dennis redraws cartographies of polar expansionism, imagining African exploration of the Arctic in Black Earth Study Room.

Tidal Body (2022), New Mineral Collective (Emilija Škarnulytė and Tanya Busse). Photo: Kjell-Ove Storvik

Since 1992, Lofoten has been home to Nordland Artscape, an initiative designed to bring contemporary art to this remote part of northern Norway. Close to the festival’s main site, a sculpture by Dan Graham consists of a triptych of three, slightly curved mirrors that reflect the landscape back to itself. Correspondence related to the work can be found at the Nordland Cultural Centre as part of the biennale. It provides a record of how, as Urbano Ragazzi put it, ‘communities gather around these artefacts’, thus eschewing the myth of the solitary artist.

Like Graham’s sculpture, the event aims to hold a mirror up to its location. Urbano Ragazzi like the idea that a ‘biennale could jump in as a UFO’ to deliver strange messages to its inhabitants. Message from a Star (Solar Symphony), an outdoor sculpture by Haroon Mirza, sits on a small hill outside the former village school. Its two strips of solar panels activate an AI-generated, electronic melody that is endlessly changing. The sound is ambient enough to be ignored, but hypnotic enough to pull in passers-by. As I listen to the piece in the September sun I catch sight of a bird on a nearby roof, cawing, as if he’s listening to it too.

The Lofoten International Art Festival (LIAF) is at various venues in the Lofoten Archipelago until 2 October.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home