The Oxford Botanic Garden – which celebrates its 400th anniversary this year – is the earliest university botanic garden in Britain. It was founded in 1621 with a donation by Henry Danvers, 1st Earl of Danby for a ‘Garden for Physical Simples’ to be used to teach Oxford university students about medicinal plants. Medicines had traditionally been derived from local plants, with apothecaries, often accompanied by a physician, using local experts (usually herb women) to bring them the plants. As new species came to Europe from the Near East and the Americas, it was necessary to distinguish those that were medicinally active and those that were poisonous. You also had to know the best time to gather them, which part of the plant to use, how to store them, how to combine them, and what dose to give. The existing books, or herbals, were not sufficient. The universities played a significant role in promoting an empirical study of botany (which eventually developed from a polynomial naming system to Carl Linnaeus’ binomial system used today) and gardens for the cultivation of ‘simples’, remedies from natural sources centred on one plant, were laid out as educational facilities attached to universities. Here, the quality and authenticity of the plants could be guaranteed.

The earliest university physic garden still at its original site is in Padua, founded in 1545 by the Republic of Venice at the request of the Professor Simplicum, Francesco Bonafede. (A garden had been founded in Pisa in 1543 but it was relocated from its original site on the banks of the Arno to its current location in the 1590s.) It was designed by the Bergamese architect Andrea Moroni and laid out as a circular garden, echoing Dante’s vision of Paradise in the Divine Comedy. An enclosing wall was surrounded by a ring of water and a square garden, divided into quarters, was set out within the circle. When the English naturalist John Ray visited Padua in 1664, he recorded that it was ‘well stored with simples but more noted for its prefects, men eminent in their skill in Botanics’.

The garden at Oxford was established on the edge of the city, just outside the East Gate. It was on low-lying meadow ground held by Magdalen College that had been a Jewish cemetery until 1293, after the expulsion of Jews from England by Edward I. The topographer Thomas Baskerville described the setting in the 1680s as ‘aptly watered with the River Charwell by it gliding’. The initial task was to raise the levels with 4,000 loads of ‘mucke and dunge’ to prevent it from flooding. It still flooded periodically, including in 1663 when the rising waters ‘drowned most part of the Phisick Garden’, and in 1882 when the professor’s house could only be reached on planks.

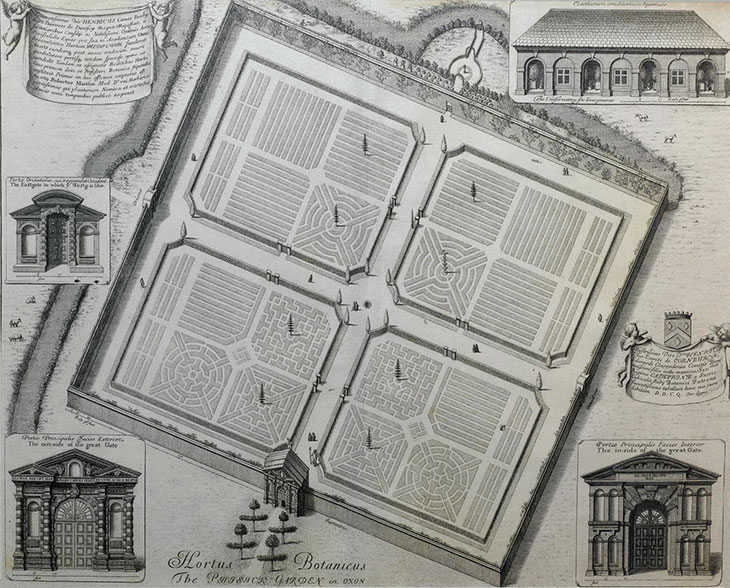

As was typical of gardens of this period, it was laid out as a square with two walks that intersected at a well in the centre and divided the garden into quarters. High stone walls were built around the garden in around 1623 and three gateways were added in 1632 – the main gate by Nicholas Stone, Inigo Jones’s master mason, with smaller gates to the west and east. The walled garden is shown in David Loggan’s bird’s-eye view of 1675, along with the three gates: here we can see that each quarter of the garden was surrounded by trellis work and further divided into four. By this date the garden had formal topiary planting around the quarters and at the entrance and while most of the beds were arranged in a linear fashion, some quarters were laid out as knots or in other geometric designs, following the fashion in private gardens. Loggan’s plan also shows a greenhouse along the south side of the High Street, built to house evergreens, which were wheeled out in pots in milder weather. (That structure was demolished in 1780 when the road was widened to improve the approach to Magdalen Bridge.)

Engraving of the Oxford Physic Garden, England, 1675, David Loggan, printed in Oxonia Illustrata (1675). Science Museum Group Collection. © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Jacob Bobart the Elder, who was appointed as the first Superintendent in 1642, produced the earliest scientific list of the plants and trees growing in the garden: Catalogus plantarum horti medici Oxoniensis (1648). Of some 1,400 plants listed, 600 were British and many were Canadian. The catalogue includes the Virginian spiderwort (Tradescantia virginiana), which was sent to John Tradescant the Elder, the botanist and gardener, from an expedition to Virginia in the 1617. Tradescant was among several botanists, herbalists and apothecaries who had formed private gardens of medicinal herbs or rarities prior to the Oxford physic garden. John Gerard, for example, had one in Holborn, and published a catalogue in 1596 listing 1,030 plants.

A manuscript catalogue of plants in the physic garden now in the British Library includes a list of native plants growing in the vicinity, as well as simple and composite recipes. These are marked with prices and divided into categories such as waters, balsams, gums and resins, sugars, salts, and marine. Prices range from the relatively cheap Aqua Alchimilla at nine pence and balsam of Chamamile at thruppence to opopanax at two pounds, Absynthis at one pound four shillings, and Ambra grisea (sperm whale) at six pounds. Advice on preparations could be found in texts such as the apothecary Nicholas Culpeper’s The English Physitian Enlarged (1666). Culpeper wrote that you should only use leaves that were ‘green, and full of juyce, pick them carefully, and cast away such as are any way declining, for they will putrifie the rest’. Seeds should be ripe and just about to fall before they were picked, then dried a little. Roots, meanwhile, should be dug up in dry weather – with soft roots to be dried in the sun, hard roots anywhere. Flowers should also be left to dry in the sun.

The diarists John Evelyn and Samuel Pepys visited the Garden under Bobart the elder’s stewardship. Evelyn, who had visited the physic gardens in Leiden, Pisa, Padua and Paris in the 1640s, found no ‘extraordinary curiosities, besides very good fruit’ (he lists olive trees and rhubarb) when he visited in 1654 but ten years later mentioned large locust trees and ‘some rare plants under the culture of old Bobart’. Jacob Bobart the Younger was appointed as Superintendent in 1679 and became the first Professor of Botany at the University. By the 1680s there was a wider range of plants on display and the collection had increased to some 3,000 plants. Thomas Baskerville described the garden as ‘being a matter of great use & ornament, prouving serviceable not only to all Physitians, Apothecaryes, and those who are more immediately concerned in the practice of Physick, but to persons of all qualities serving to help the diseased and for the delight & pleasure of those of perfect health’.

From the mid 17th century the garden was a place where natural philosophers and private collectors exchanged information. Mary Somerset, Duchess of Beaufort collected, studied and grew plants including exotics, liaising with Jacob Bobart and Hans Sloane, among others, on nomenclature. She also exchanged plants with Bobart, who in the 1690s sent her ornamental and greenhouse plants including ‘diverse very fine sorts’ of iris, ‘The Perfuming Chery of Arabia’, ‘And an excellent plant of my jewell of a Primrose’, as well 75 sorts of choice seeds ‘which are either newly come to my hands from abroad, or gather’d last in our owne Garden’. Bobart’s correspondence with Hans Sloane, meanwhile, refers to the latter’s collection of ‘Exotick Druggs in quantity’; Bobart had received books from Sloane and was due to receive seeds from Sloane via the Royal Society.

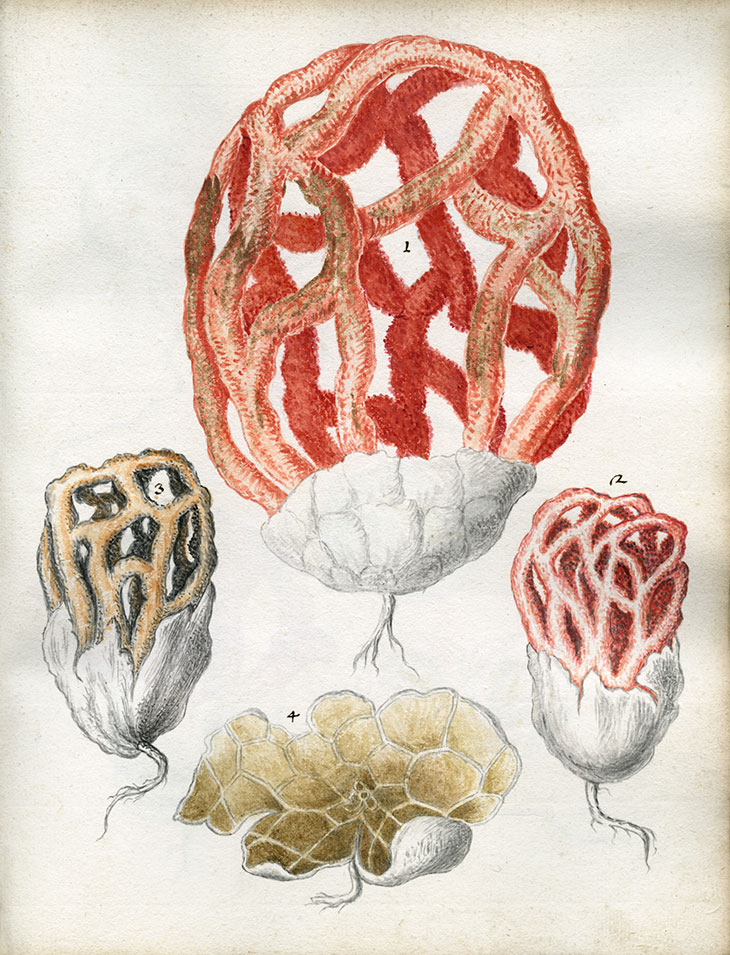

On view in ‘Roots to Seeds: 400 Years of Oxford Botany’ at Bodleian Libraries: Basket stinkhorn (Clathrus ruber) from Bruno Tozzi’s Sylva fungorum (1724). Sherardian Library of Plant Taxonomy, Oxford

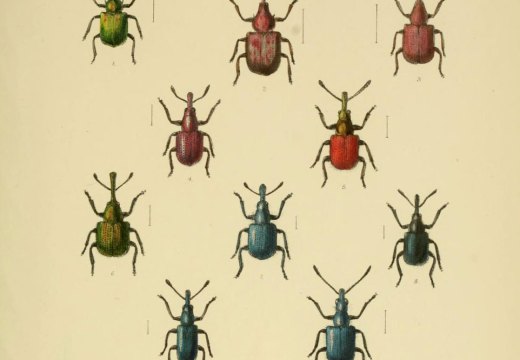

Plant collecting calls both for skill and luck, not least because the plants flower, come into leaf, and set seed at different times. It was difficult for these early collectors to preserve specimens, live or dried. As the 18th-century naturalist Mark Catesby wrote of the American lotus: ‘the flowr I could not preserve so have sent this scetch’. The ephemeral nature of the plants meant that recording them accurately was a key part of the research process. Highly skilled botanical art supported written records and preserved specimens in herbaria.

By the mid 18th century the university had neglected to fund the garden adequately. There were concerns about the preservation of the specimens in the herbarium due to dampness. The second Sherardian Professor of Botany, Humphrey Sibthorp, is known to have only given one lecture while superintendent from 1747–84. On one occasion Joseph Banks, who studied at Christ Church in 1760–63, asked Sibthorp for a teacher of botany; Mr Lyons, a botanist and astronomer from Cambridge, was paid for privately by the students.

In 1834, Charles Daubeny was appointed Professor of Botany at Oxford. He renamed the Physic Garden as the Oxford Botanic Garden and made proposals that were aimed at raising the standard of plant science at Oxford. He proposed that the space outside the walls should be dedicated to plants employed in medicine, agriculture, or the arts, with the remainder (that within the garden walls) as an experimental garden, for ascertaining the effects of soils, or chemical agents, upon vegetation and other research. He also proposed the large basin for aquatic plants that is in the centre of the walled garden area. In the 1850s glasshouses were built in the positions occupied today and the plant beds were altered, briefly, to a ‘Gardenesque’ design of irregular beds. Rectangular beds were reintroduced in the 1880s. The Department of Botany was established at the same time and the taxonomic beds were planted. A room known as the Daubeny Lecture Theatre was created, later becoming the Daubeny Laboratory before reverting back to a lecture theatre.

The Water Lily House at Oxford Botanic Garden, photographed in 1870. Courtesy Oxford Botanic Garden

In the 1930s, the Department of Botany moved out of the botanic garden to a new building. The garden’s focus moved towards horticulture and recreation. The garden has always contained a mixture of native and non-native plants but it now contains plants that are of historical, ecological, economic, and aesthetic interest as well as those of medicinal use. Still, visitors today can explore the ‘Medicinal Collection’, arranged around the diseases the plants are used to treat (either directly or modified synthetically), and the ‘1648 Collection’, which includes plants listed in Bobart’s catalogue. The garden has benefited from focused care during the pandemic, and looks at its best, with luxuriant planting outside the wall to the east, alongside the river. Other areas are specifically designed to need little care, such as the Merton Borders, a sustainable horticultural development sown in 2011, with plants able to withstand warmer summers and drought conditions.

A view of the Merton Borders at the Oxford Botanic Garden, photographed in summer 2018. Courtesy Oxford Botanic Garden

An exhibition, ‘Roots to Seeds: 400 Years of Oxford Botany’, forms part of the anniversary events in 2021 (until 24 October). The display at the Bodleian Libraries shows manuscripts, early printed books, original seeds and dried specimens, and models to present the history of plant science and the role of the university in its evolution. The different effects of plants are illustrated through mandrake – which depending on strengths can cause drowsiness, anaesthesia, or even death – and the carrot family, which includes useful spices and herbs such as coriander and parsley but also hemlock, the toxic plant that killed Socrates. The exhibition also points out that ‘botanical collections cannot be disassociated from centuries of inequality’ and that plant collecting was intrinsically linked to colonialism. It acknowledges the numerous unrecorded people involved in the field, who helped source and identify plants on the expeditions. And it concludes with a section on contemporary issues around food security and climate change.

Plants are essential to our existence. They are of commercial and cultural value – whether used in construction, medicine and horticulture – but more importantly each plant plays a role in the ecosystem. They are the source of the oxygen we breathe. The State of the World’s Trees report, published this year by Botanic Gardens Conservation International, finds that 30 per cent of trees are at risk of extinction. While the best place to preserve trees is in their natural habitat, this is not always possible and ex-situ conservation is essential. A third of the world’s tree species are currently growing in botanic gardens or seed banks. With climate change, the role of botanical gardens in researching and recording plants, and in educating the public on their importance, has never been so vital. Although it is also worth noting that one of the threatened groups of trees is the magnolia, at risk due to unsustainable plant collection – a reminder that the role of conservation must be finely balanced.

Camilla Beresford is a consulting landscape architect and historian.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home