Art postcards have a curious status. They still gather in hefty clumps at the exits of exhibitions, the cheapest souvenirs of a big show (though now hardly actually cheap), so presumably they must still sell. Yet they also seem entirely defunct. Who, now, sends postcards? Perhaps there is a small chance children still send a card from the seaside to their granny or a few older hold-outs communicate in this eccentric medium (as I occasionally do).

What, then, happens to these art cards? Do they sit on someone’s shelf for a couple of weeks until a new image comes along? Are they pinned on cork boards or stuck to fridges or student walls? Magnetised to fridges? I really have no idea.

I’ve been thinking about postcards over the last few years, more than I might have liked. I was going through and clearing out my dad’s stuff and he collected art postcards (alongside almost any other kind of card and, seemingly, everything other type of printed matter including tangerine wrappers). He was a completist. If he visited an exhibition, he’d buy one of every card. Not to send but to have, to archive, to put in a shoebox, alphabetised, taxonomised and set in order.

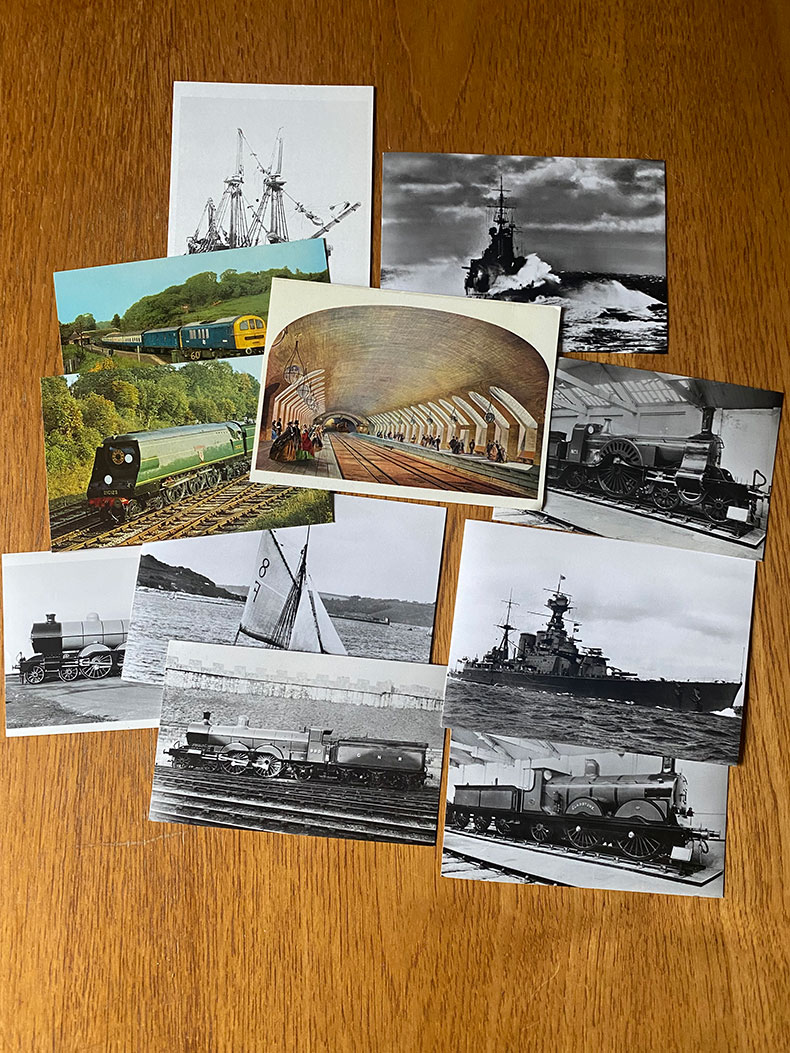

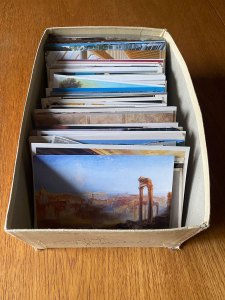

Photo: the author

He had perhaps a hundred boxes of varying sizes containing God knows how many cards. When the boxes ran out, there were black bags, jiffy bags, shopping bags, the often beautiful bookshop and gallery bags the cards came in, old envelopes and, finally, the floor. Everything co-existed. From photos of mosaics in Italian churches and endless Rubenses and Rembrandts, to oddly over-coloured tourist views of Kent or London (he was born in London and grew up in Kent), some new, some old. There were razor-sharp black and white reproductions of oil paintings from over a century ago (often cards with frilly edges), sepia images of Edwardian tourist hotspots and pictures of locomotives and fishing boats. There were tribal fetishes and church interiors from far-flung parishes. Everything from Aachen to Zurbarán. In a way it was an incredible record of a life of visiting art exhibitions, rural museums, tourism, holidays, work trips (he was a journalist) and random finds from second bookshops that have long since disappeared. But, like so many of the things we accumulate over our lives, it lost a lot of its value (by which I don’t mean money), its meaning and its associations by the time it fell to me. For my dad, each of these images represented a moment and a place, even if, as with the photo of the Sistine Chapel ceiling bought in an Edinburgh junk shop in the 1970s (it was written on the back in pencil), or a reproduction of a Lowry acquired at a Budapest fleamarket, the two might be radically disconnected.

The art postcard was once an almost magical way of disseminating the collection, of communicating art outside the academy. Images were sent and pored over, often by others who would never get to that particular gallery, would never see that particular work. It was a brilliant medium for propagating fine art into popular culture. Now people snap the pictures at a gallery or pose with them for a selfie, which has itself hugely changed the way we see art. The card is not dead but it is barely breathing.

Postcards with particular views or celebrity signatures may have some value to collectors. Art postcards have none. So what to do with this collection? For me at least, it had those sentimental associations, the memories attached to my dad, our tolerance of his collecting (others might call it obsessive hoarding), my mum’s eye-rolling but also the cultural value of this bank of images, a record of a life, relatively random in their ‘archiving’, the odd, often illuminating juxtapositions of artists and things. But once my dad had died they shed their memory, their value.

Although art postcards still exist, the internet has seemingly killed the point of them. Any image of any artwork is a click away, accessible and sent in milliseconds. It’s true that those digital images are even more ephemeral than postcards, flickering on a screen and gone again once you’re back to the next page while postcards might at least stick around on a window sill or a mantelpiece. But if every image is available at any time, why would you need to store dozens of boxes, most not in any semblance of order, some not even taken out of their gallery bags, gathering dust?

IMG_2880 Photo: the author

Do postcards have an afterlife? It turns out, against my expectations, that they do. When my daughters, both students, found the endless boxes of images they enthusiastically rifled through the boxes, picking images that appealed, anything from 1920s advertising and Suprematism to Pop art and architecture and made themselves walls of images using BluTack. Perhaps to a younger generation brought up with fleeting images these things which once appeared so ephemeral themselves now look oddly permanent. It’s something I’ve encountered at the Cosmic House, the Holland Park house museum of my late friend Charles Jencks, where I am now the ‘Keeper of Meaning’. His downstairs cloakroom has a dado of postcard-sized frames inhabited with unusual images, the idea being that a constantly-changing panorama of images sent or collected from around the world would create a momentary diversion, for constipated guests, perhaps. But now he is gone the cards do not change any more. They are fixed, the images of a half-completed Eiffel Tower, a Dutch courtyard, the Pompidou Centre, a massive Roman stone hand, views of the world captured and slowly fading.

I picked out some cards form my dad’s collection too, either because the images interested me or because I thought it’d be incredibly frustrating to need to send a postcard one day and have to go out and buy one. The others, tens of thousands of them, have (against all my expectations) found themselves a home in an archive of art ephemera. But more than this I wonder if, once they are almost gone as a medium, they might return as a luxury? It’s something I think we’ve noticed with vinyl LPs and with newspapers. The LP now outsells the CD, a tangible object capable of embodying associations, memories and moods. The daily newspaper was once a staple of civilised life. Plunging sales and free online news have seen the papers decline into semi-negligibility. Some, like the once widely-consumed Evening Standard, are now free throwaways, losing any semblance of value. I was reminded by the corners of my dad’s later postcard collection that they too went through this phase. At some point in the 1990s, card-dispensing racks appeared in bars and clubs, often near the toilets, cards advertising anything from art exhibitions to TV shows. They were often graphically striking, funny, cool even. But the fact that they were free eroded their value. Now the expensive weekend newspaper has arguably returned as a treat, its crinkling pages an excuse to sit and read, undistracted by the screen. To sit in the garden or in a cafe with a paper on a Saturday morning seems a wonderful indulgence. Likewise, when a postcard drops on my doormat it is accompanied by a moment of recognition and anticipation. Its image studied for longer than an Instapost and it is usually placed on a shelf or a dresser for a while, becoming a part of the background to everyday life for a couple of weeks. Perhaps the physical image, that once-so-familiar 6×4 inch format, will return as a moment of memory and pleasure. If any of us will be able to afford a stamp, that is.

What’s the point of old postcards?

Photo: the author

Share

Art postcards have a curious status. They still gather in hefty clumps at the exits of exhibitions, the cheapest souvenirs of a big show (though now hardly actually cheap), so presumably they must still sell. Yet they also seem entirely defunct. Who, now, sends postcards? Perhaps there is a small chance children still send a card from the seaside to their granny or a few older hold-outs communicate in this eccentric medium (as I occasionally do).

What, then, happens to these art cards? Do they sit on someone’s shelf for a couple of weeks until a new image comes along? Are they pinned on cork boards or stuck to fridges or student walls? Magnetised to fridges? I really have no idea.

I’ve been thinking about postcards over the last few years, more than I might have liked. I was going through and clearing out my dad’s stuff and he collected art postcards (alongside almost any other kind of card and, seemingly, everything other type of printed matter including tangerine wrappers). He was a completist. If he visited an exhibition, he’d buy one of every card. Not to send but to have, to archive, to put in a shoebox, alphabetised, taxonomised and set in order.

Photo: the author

He had perhaps a hundred boxes of varying sizes containing God knows how many cards. When the boxes ran out, there were black bags, jiffy bags, shopping bags, the often beautiful bookshop and gallery bags the cards came in, old envelopes and, finally, the floor. Everything co-existed. From photos of mosaics in Italian churches and endless Rubenses and Rembrandts, to oddly over-coloured tourist views of Kent or London (he was born in London and grew up in Kent), some new, some old. There were razor-sharp black and white reproductions of oil paintings from over a century ago (often cards with frilly edges), sepia images of Edwardian tourist hotspots and pictures of locomotives and fishing boats. There were tribal fetishes and church interiors from far-flung parishes. Everything from Aachen to Zurbarán. In a way it was an incredible record of a life of visiting art exhibitions, rural museums, tourism, holidays, work trips (he was a journalist) and random finds from second bookshops that have long since disappeared. But, like so many of the things we accumulate over our lives, it lost a lot of its value (by which I don’t mean money), its meaning and its associations by the time it fell to me. For my dad, each of these images represented a moment and a place, even if, as with the photo of the Sistine Chapel ceiling bought in an Edinburgh junk shop in the 1970s (it was written on the back in pencil), or a reproduction of a Lowry acquired at a Budapest fleamarket, the two might be radically disconnected.

The art postcard was once an almost magical way of disseminating the collection, of communicating art outside the academy. Images were sent and pored over, often by others who would never get to that particular gallery, would never see that particular work. It was a brilliant medium for propagating fine art into popular culture. Now people snap the pictures at a gallery or pose with them for a selfie, which has itself hugely changed the way we see art. The card is not dead but it is barely breathing.

Postcards with particular views or celebrity signatures may have some value to collectors. Art postcards have none. So what to do with this collection? For me at least, it had those sentimental associations, the memories attached to my dad, our tolerance of his collecting (others might call it obsessive hoarding), my mum’s eye-rolling but also the cultural value of this bank of images, a record of a life, relatively random in their ‘archiving’, the odd, often illuminating juxtapositions of artists and things. But once my dad had died they shed their memory, their value.

Although art postcards still exist, the internet has seemingly killed the point of them. Any image of any artwork is a click away, accessible and sent in milliseconds. It’s true that those digital images are even more ephemeral than postcards, flickering on a screen and gone again once you’re back to the next page while postcards might at least stick around on a window sill or a mantelpiece. But if every image is available at any time, why would you need to store dozens of boxes, most not in any semblance of order, some not even taken out of their gallery bags, gathering dust?

IMG_2880 Photo: the author

Do postcards have an afterlife? It turns out, against my expectations, that they do. When my daughters, both students, found the endless boxes of images they enthusiastically rifled through the boxes, picking images that appealed, anything from 1920s advertising and Suprematism to Pop art and architecture and made themselves walls of images using BluTack. Perhaps to a younger generation brought up with fleeting images these things which once appeared so ephemeral themselves now look oddly permanent. It’s something I’ve encountered at the Cosmic House, the Holland Park house museum of my late friend Charles Jencks, where I am now the ‘Keeper of Meaning’. His downstairs cloakroom has a dado of postcard-sized frames inhabited with unusual images, the idea being that a constantly-changing panorama of images sent or collected from around the world would create a momentary diversion, for constipated guests, perhaps. But now he is gone the cards do not change any more. They are fixed, the images of a half-completed Eiffel Tower, a Dutch courtyard, the Pompidou Centre, a massive Roman stone hand, views of the world captured and slowly fading.

I picked out some cards form my dad’s collection too, either because the images interested me or because I thought it’d be incredibly frustrating to need to send a postcard one day and have to go out and buy one. The others, tens of thousands of them, have (against all my expectations) found themselves a home in an archive of art ephemera. But more than this I wonder if, once they are almost gone as a medium, they might return as a luxury? It’s something I think we’ve noticed with vinyl LPs and with newspapers. The LP now outsells the CD, a tangible object capable of embodying associations, memories and moods. The daily newspaper was once a staple of civilised life. Plunging sales and free online news have seen the papers decline into semi-negligibility. Some, like the once widely-consumed Evening Standard, are now free throwaways, losing any semblance of value. I was reminded by the corners of my dad’s later postcard collection that they too went through this phase. At some point in the 1990s, card-dispensing racks appeared in bars and clubs, often near the toilets, cards advertising anything from art exhibitions to TV shows. They were often graphically striking, funny, cool even. But the fact that they were free eroded their value. Now the expensive weekend newspaper has arguably returned as a treat, its crinkling pages an excuse to sit and read, undistracted by the screen. To sit in the garden or in a cafe with a paper on a Saturday morning seems a wonderful indulgence. Likewise, when a postcard drops on my doormat it is accompanied by a moment of recognition and anticipation. Its image studied for longer than an Instapost and it is usually placed on a shelf or a dresser for a while, becoming a part of the background to everyday life for a couple of weeks. Perhaps the physical image, that once-so-familiar 6×4 inch format, will return as a moment of memory and pleasure. If any of us will be able to afford a stamp, that is.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

The unruly life of museum postcards

We’re all building miniature museums at home, and postcards of paintings have taken on a life of their own

The postcards that paved the way for the Russian Revolution

Anti-tsarist postcards were an important, and often beautiful, form of radical propaganda in Imperial Russia

Geometry, pastries and paint: an interview with Wayne Thiebaud

‘I started painting these triangles and turning them into pies. I thought, “My God! I’m done in! Nobody will ever take me seriously!”’