Few architectural projects can hope to mimic the much-touted ‘Bilbao effect’: the fairy-tale transformation of a weary, post-industrial area into a cultural hub. Erroneously known as the building inspired by a scrunched-up piece of paper, the Guggenheim Bilbao, which opened in 1997, has become Frank Gehry’s biggest success story. However, ‘the Bilbao effect’ shouldn’t be misinterpreted as ‘the Guggenheim effect’. Bilbao was ripe for regeneration – there was already an energy bubbling beneath the surface of the city and an active desire for change. There may be a certain glamour to the rumours of a Guggenheim East London for E20, the arty avatar of the former Olympic park, but a multi-million lease of the Guggenheim name won’t necessarily buy success –as short-lived ventures in Berlin and Las Vegas have shown. It’s not surprising that the Finns are knitting their brows over the proposed Guggenheim Helsinki.

Twenty years after establishing the partnership with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, the museum is staging ‘The Art of our Time’, a sequel to its inaugural show ‘The Art of this Century’. Sprawling across all floors, the exhibition is a three-tiered showcase of Bilbao’s permanent collection of art post-1945, accompanied by early 20th-century avant-garde works on loan from the Foundation.

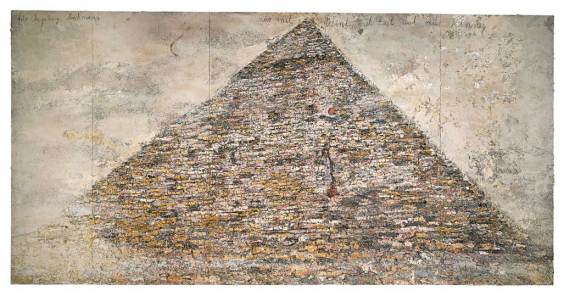

Only with Wind, Time, and Sound (Nur mit Wind, mit Zeit und mit Klang) (1997), Anselm Kiefer. Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa

The curation emphasises the distinct identity of Bilbao’s collection and its development over the last two decades, brushing aside the typical criticism of cultural imperialism. Instead, we are fed a narrative about complementary values: the New York and Bilbao Guggenheims share out the chronology of the 20th century, and coalesce with their own collections of contemporary art. Displaying key works such as Robert Rauschenberg’s Barge (1962–63) and Mark Rothko’s Untitled (1952–53), as well as an extraordinary group of large-scale paintings by Anselm Kiefer transcendently juxtaposed with Joseph Beuys’ Lightning with a Stag in its Glare (1958–85), Bilbao plays its most powerful trump card: scale. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Richard Serra’s monumental The Matter of Time (1994–2005), one of a number of vast permanent installations including Jeff Koons’ Puppy (1992) and Louise Bourgeois’s Maman (1999).

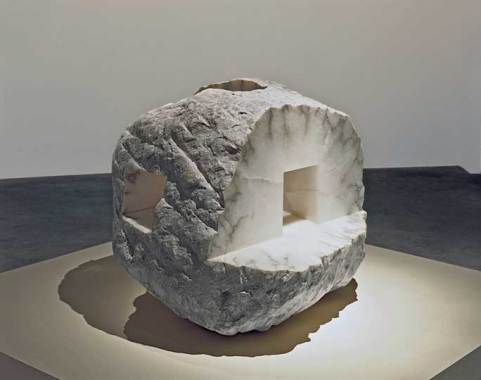

A distinct emphasis on Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art is balanced by a local focus on Basque art, specifically the sculptures of Eduardo Chillida and Jorge Oteiza. Monographic displays of their work are presented in spaces open to the third floor-balconies, the hollowed-out core of the building echoing the sculpted forms. Installations by Basque artists Cristina Iglesias and Txomin Badiola appear in the contemporary collection on the ground floor, where works by figures including Ai Weiwei, Danh Vō and Sopheap Pich suggest a slightly over-insistent internationalism.

Intriguingly, this section of the show includes a work from the incipient Guggenheim Abu Dhabi collection, El Anatsui’s golden wall-hanging Earth’s Skin (2007). It may be made of bottletops, but its tapestry form has the force of a feudal power symbol, and all the glitzy allure of the Emirates Palace Hotel lobby. It would be reductive to view this work as a microcosm of the Abu Dhabi collection, which is reportedly geared towards the modernist legacy and the emergence of Middle Eastern contemporary art. Yet its appeal seems in keeping with the designs for Gehry’s next Guggenheim icon, set to open in 2017: the renderings give it the appearance of an adventure island straight out of the world of gaming.

When it comes to collecting and displaying works of art, Guggenheim lends itself less easily to criticism. Weighed down by the cumbersome claim ‘The Art of our Time’, you might expect the Bilbao exhibition to be a bombastic display of curatorial showmanship. There are various islands of self-congratulation, little educational (‘Didaktika’) spaces where you can read bouncing wall texts about the brilliance of the Guggenheim brand. Yet, in the gallery spaces, the art is left to speak for itself; understated curation and subtle visual associations allow the viewer to witness the power of each piece without further explanation. The overall result is neither canned art history nor a corporate manifesto, but a coherent display of exceptional artworks, elegantly outlining some of the thoughts and forms threaded throughout the last 100 years.

‘The Art of our Time’ is at the Guggenheim Bilbao until 3 May 2015.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Untitled (Jealousy II) [Sin título (Celosía II)] (1997), Cristina Iglesias. Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Sin-titulo-Cristina-Iglesias-2.jpg?resize=247%2C331)

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home