Describing the process of making the digital print Chiara & Chair (2004), which together with the later painting Hotel du Rhône (2005) developed from a display of his work Lobby (1985–7) in the foyer of the Hotel du Rhône in Geneva, Richard Hamilton characterised himself as a ‘confirmed collagist.’ The interconnections between these three works, nested inside each other like Russian dolls, underline how the collage principle extended beyond Hamilton’s individual compositions to shape his entire oeuvre.

The retrospective treatment given Hamilton by Tate Modern affords viewers the luxury of tracing the links between different sections of his career, together with the refinements he made within series such as Swingeing London (1967) and Kent State (1969). Collage informed Hamilton’s voracious engagement with media, which ranged from oil and watercolour through magazine cut-ups, exhibition design and installation to screenprints, photography and digital manipulation – but it was also a central part of his politics.

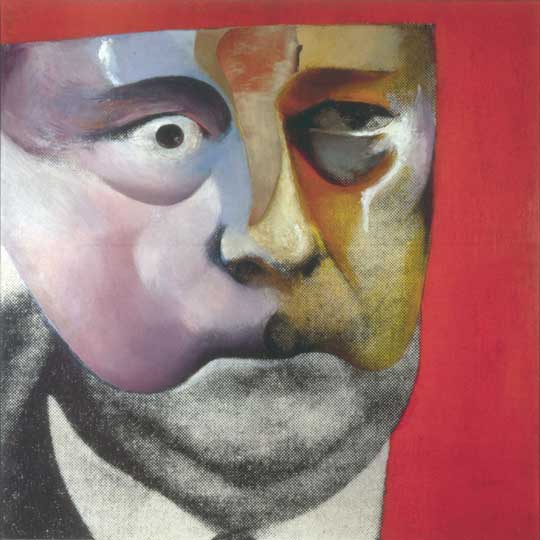

Portrait of Hugh Gaitskell as a Famous Monster of Filmland (1964), Richard Hamilton Arts Council Collection, South Bank Centre, London © The estate of Richard Hamilton

Hamilton created his earliest explicitly political image, Portrait of Hugh Gaitskell as a Famous Monster of Filmland (1964), by overlaying a photograph of the pro-nuclear-missiles Labour leader with sweeps of nacreous, irradiated colour borrowed from B-movie baddies. While later images such as the deliberately grotesque Shock and Awe (2010), for which Hamilton spliced Tony Blair with the figure of a gun-toting cowboy, have been critiqued for their lack of subtlety, the schlocky-horror Portrait testifies that Hamilton, for all his refinement, never shied away from blatancy and delighted in a bit of mischievous shock and awe on his own terms.

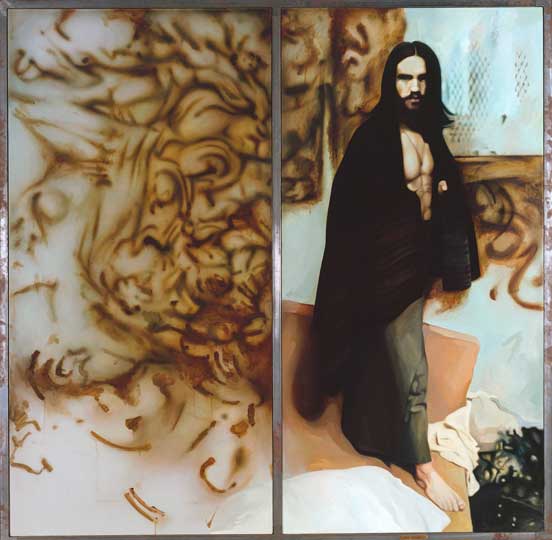

These works are complemented at Tate Modern by Hamilton’s major series of three painted diptychs, The citizen (1981–3), The subject (1988–90) and The state (1993), which respectively depict a republican prisoner conducting a ‘dirty protest’ at Long Kesh in Northern Ireland, a loyalist Orangeman on parade, and a British soldier with his rifle tentatively raised. Television news stills of protesters and hunger strikers denied the status of political prisoners provided the initial germ for the three paintings, and together they constitute a major statement on the polarisation of Irish politics during the 1980s, and on the global mediatisation of conflict and its irruption into domestic space.

The citizen, The subject and The state expand on the layers of production involved in earlier projects like Kent State, in which the group of screen prints evolved from a photograph Hamilton took of his television monitor, broadcasting news of student massacres at an anti-Vietnam protest on the US university’s campus. Kent State demonstrates how Hamilton not only used the collage process to deconstruct the slick surfaces of product placement, as he had done in his withering commentaries on gendered advertising such as $he (1958–61) and Hers is a Lush Situation (1957), but also to experiment with the deterioration of images as they merge and disperse through multiple receptors and transmitters.

Over the course of the prints, the image becomes so blurred that it is difficult to make out what is being shown. The haunting content of the original news images is replaced by an equally haunting sense of loss, and of the danger of forgetting certain histories. In this respect, as the works in this consistently engaging exhibition show, collage also provides a means of updating and re-combining – a possible mode of resistance.

‘Richard Hamilton’ is at Tate Modern, London, until 26 May 2014.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home