Initially scheduled to open in March, the National Gallery’s exhibition of paintings by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654 or later) thankfully survived the closure of the museum by the pandemic and has now been unveiled to rapturous reviews. This small but significant show is worth visiting for the chance to appreciate the career of one of the great painters of 17th-century Italy.

The aim of the exhibition is to clarify the oeuvre of Artemisia by presenting the best-documented, most securely attributed paintings, including some that have only recently been rediscovered. The show also comes on the back of the National Gallery’s acquisition of an early painting of the artist herself in the guise of a martyred saint, one of the recent discoveries that change our view of her career. Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria (c. 1615–17) entered the gallery’s 2,300-strong collection in 2018 as one of only 21 paintings by women, a depressing statistic. It is a small step forward to have on view, even temporarily, a body of works representing a woman’s career as a painter in early modernity.

Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria (c. 1615–17), Artemisia Gentileschi. National Gallery, London

The show includes 30 paintings by Artemisia (out of a potential group of 50–60 works) together with a few by other painters of the period, including her father Orazio Gentileschi. This focus on the artist alone puts due emphasis on a singular figure who has recently been illuminated by new scholarship. However, to isolate her works from those of her contemporaries may lead to new problems in our understanding of her place and the place of other women artists in seicento culture.

New studies and recent exhibitions of Lavinia Fontana and Sofonisba Anguissola, Elisabetta Sirani and Giovanna Garzoni have shed light on the influential contributions of these and other women who chose a career in painting in early modern Italy. Unlike these artists’ circumstances, Artemisia’s course was forever altered by misfortune. The trial brought in 1612 against fellow artist Agostino Tassi for raping her was shocking news far beyond Rome. When the trial ended, Artemisia married hastily and moved from Rome to Florence. The exhibition relates her life to her art through the lens of this notorious rape, on the one hand, and her proud ambition as an artist on the other.

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura) (c. 1638–39), Artemisia Gentileschi. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

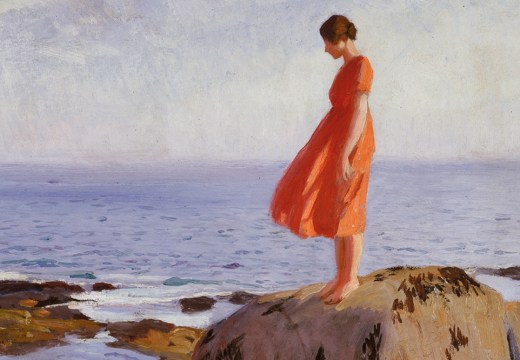

The exhibition presents her portrayal of herself as self-advertisement within subjects such as Saint Catherine or, in the final room of the show, the so-called Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (which no longer looks so much like a self-portrait, once we take into account her appearance in contemporary portraits). That she used herself as a model is attributed to pragmatic economising, since it was cheaper than hiring models. Perhaps it could be argued that her self-portrayal in such works was also a way to capitalise on the notoriety brought by her rape trial. I am not so sure.

In the wake of Caravaggio, the question of artists painting models dal vivo or dal naturale (‘from life’) is one that has preoccupied me recently. Portraying one’s own body as a model, and retaining the recognisable likeness of that body, wasn’t only convenient and cheap; it countered critical opinion about the value of idealising the human body. Reliance on the live model rooted the image in the authority of nature itself. In this light, it is all the more significant that Artemisia corresponded with and sought to work for one of the century’s great scholars of natural history as well as classical antiquity, Cassiano dal Pozzo.

There is another realm in which portraying herself in the role of historic figures also resonates – that of theatrical performance. We now know that Artemisia’s courtly surroundings in Florence, Venice and Naples put her in contact with women who were famed as actors and musicians. She paints her own likeness playing a lute, in a work from the Spada Gallery in Rome that did not make it into the exhibition, and in a work on loan here from the Wadsworth Atheneum. Virtuoso performance was an indispensable tool for the courtier.

Self-Portrait as a Lute Player (c. 1615–17), Artemisia Gentileschi. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford

Her practice of working from life helps us to understand Artemisia’s friendship and interchange with her contemporary, Giovanna Garzoni, whose still lifes, botanical illustrations and miniature paintings relied on working dal vivo. Mary Garrard has recently shed light on this friendship and its impact on their careers; an exhibition of Garzoni’s works organised by Sheila Barker took place in Florence earlier this year. It would have been splendid to see the two artists reunited here. An 18th-century source praised Artemisia Gentileschi for her naturalism in still-life painting, which implies that an entire category of her oeuvre with links to that of Garzoni is now missing, since no such images are now known.

While the catalogue wisely cautions us against too simplistically connecting Artemisia’s life and art, the curator’s choice to display the actual court document recording her rape trial, and her recently rediscovered letters to her aristocratic lover, seems to push us in this direction. While the latter are indeed important to our understanding of the artist and her world, by this point in the itinerary of the exhibition, I longed for more paintings, not more documents.

The second half of the exhibition, which follows strict chronological order, displays paintings that are far less consistent in style even though produced close together in time, such as The Birth of Saint John the Baptist or Saint Januarius in the Amphitheatre at Pozzuoli. Both paintings have suffered damage. They are also oddly mannered yet inert compositions; no trace of working ‘from life’ remains here. We know that towards the end of her career, in Naples, Artemisia collaborated with several different artists, including Massimo Stanzione and Viviano Codazzi. The whys and wherefores of this process of collaboration, acknowledged in the catalogue, are not well addressed in the display. How does it happen that the forceful, dramatic self-expression of the early rooms changes to this composite and rather impersonal style in the final rooms?

Esther before Ahasuereus (c. 1628–30), Artemisia Gentileschi. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It is a relief to see the juxtaposition in the very last room of Artemisia with Orazio Gentileschi, calling attention to the fact that both daughter and father worked in London at the end of the 1630s. Artemisia’s earlier Esther before Ahasuerus, probably made in Naples, and Orazio’s Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife, painted for Queen Henrietta Maria, show the importance for their courtly context of a grand scale. Both works depict the confrontation of a man and woman as if they were on a stage set, in dance-like poses, robed in gorgeously heightened colours. One can easily see them as responding to the taste for theatre at court. The exhibition as a whole makes clear that Artemisia’s shifting style responds not just to her changing emotions nor simply to a different subject matter but to changes in her environment. We are left with a picture of Artemisia’s creativity as a restless force, in dialogue with the artists around her and all the more individual and significant as a result.

‘Artemisia’ is at the National Gallery, London, until 24 January 2021.

From the November 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

What Frank Stella saw – and what he made us see