In an interview earlier this year, the National Gallery’s director, Gabriele Finaldi, confirmed a rumour that had long been in circulation: that, over the decades, a small group of artists have been given the keys to the doors of the National Gallery. Or more accurately, a ‘privilege pass’, which allows its holder to arrange out-of-hours visits to the institution. The pass is renewable on an annual basis, and is issued at the discretion of the director. Lucian Freud apparently used his all the time, bringing girlfriends he wanted to impress or visiting alone in the middle of the night, equipped with a sketchpad and pencil. As he told an interviewer in 1995, ‘I use the gallery as if it were a doctor. I come for ideas and help.’

That the National Gallery is a natural home for artists as much as artworks is a central tenet of its artist-in-residence programme, which was relaunched this year (a previous iteration, the ‘Associate Artist Scheme’, ended in 2018). The first resident is Rosalind Nashashibi, who since last September – minus a four-month hiatus necessitated by the lockdown – has been working from a studio on-site at the museum, a short stroll away from the galleries where she has regularly met with curators to talk about the paintings in their custodianship. No romantic cloak of darkness here, but rather a practical and productive arrangement that also includes financial support: as well as a £30,000 stipend, Nashashibi received a grant to cover the costs of childcare. And happily so, for during this time Nashashibi has been quite prolific, producing a series of paintings that vary widely in their subject matter and references – from Uccello’s horses to a self-portrait by Gauguin – but share a dreamy, almost ethereal quality, composed of disparate images rendered in thin washes of pigment. These are illustrated in the catalogue that accompanies the display; it would have been wonderful to see more of them in person.

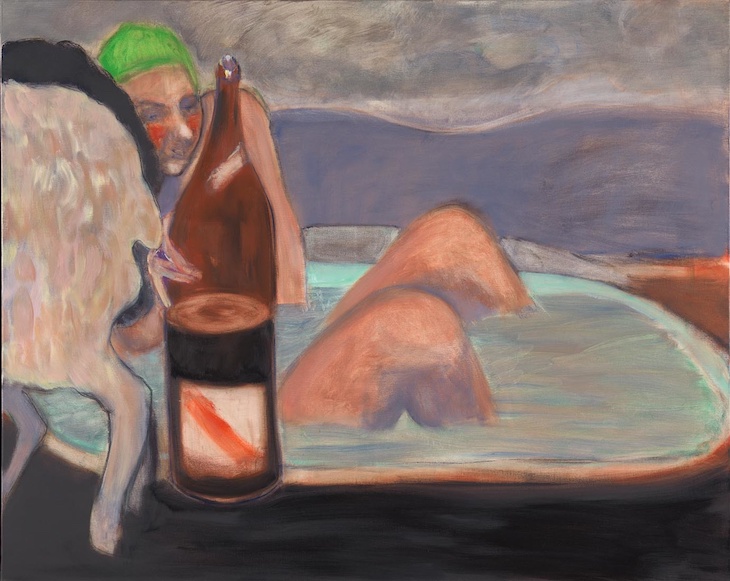

An Overflow (2020), Rosalind Nashashibi. Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam/New York

The four pieces that are on view have been selected for their relationship to – and have been hung alongside – the works Nashashibi consistently found herself drawn to during her residency: the National Gallery’s collection of 17th-century Spanish paintings. For Nashashibi, it was these works’ excesses that pulled her in – or rather, the simultaneous attraction and repulsion of the abundant yet palpably artificial feeling conveyed in their dramatic compositions. The words ‘an overflow of passion and sentiment’ (also the title of the display) are scrawled on a snake-like banner that unfurls across one of Nashashibi’s paintings, a small, enigmatic canvas that bears little to no hint of emotion. From the caption of An Overflow (2020) we learn that the composition is based on a still image of Ingrid Bergman in a swimming pool. While any distinctive features are obscured, you can easily make out a pinkish form in a swimming cap reaching up from an aquamarine abyss to grasp a glass bottle – champagne, apparently – from a lime-green ledge. The banner weaves its way through the gap between Bergman’s body and the bottle, occupying an ambiguous space akin to that of trompe l’oeil scraps of parchment bearing the names of artists or sitters in historic paintings. Yet the banner’s intended reference, the caption also tells us, is to ‘the dragon’s long tail in Velázquez’s depiction of Saint John the Evangelist nearby’.

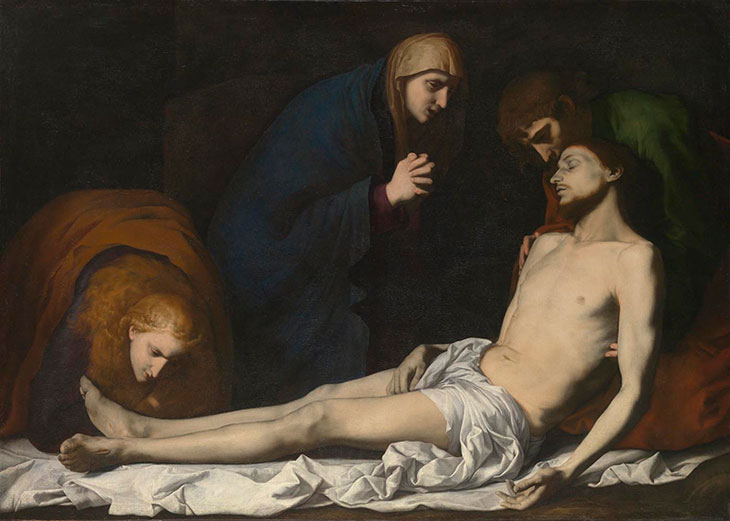

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ (early 1620s), Jusepe de Ribera. © The National Gallery

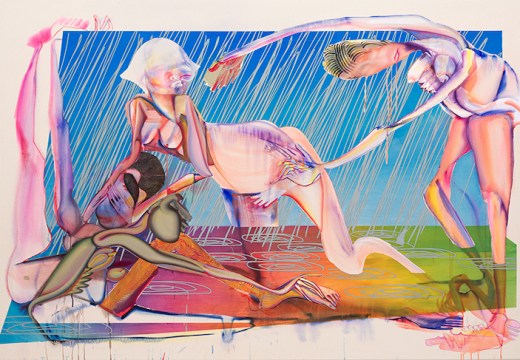

A similar direct quoting of compositional elements is evident in the other paintings in the display. Phosphorous Malvolio (2020) lifts the legs of Philip IV in Velázquez’s portrait of the Spanish king, dressing them in the yellow, cross-gartered stockings of Shakespeare’s ill-tempered servant. An outreached arm in A Drop of Scent (2020) echoes that of Zurburán’s Saint Francis in Meditation, while the palette borrows from a nearby Ribera. The tub of water in Winter Solstice (2020) forms the same shape as the arena in Velázquez’s Philip IV hunting Wild Boar (La Tela Real) – a painting which, Nashashibi told me at the press view for the display, she has returned to more than any other, for that ‘ghostly’ expanse of sandy terrain at its centre.

Winter Solstice (2020), Rosalind Nashashibi. Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam/New York

La Tela Real one of a handful of works for which Nashashibi has written short responses that are displayed alongside their usual captions in the gallery. ‘This strange painting looks like a metaphor for painting itself,’ her caption reads. The space of the arena ‘hollows out the composition and makes it seem like an abstract work; a canvas within a landscape’. Nashashibi isn’t the only artist to have found a particular affinity for this painting: when R.B. Kitaj was working on his show at the National Gallery in 2001, he kept coming back to it, too.

Philip IV hunting Wild Boar (La Tela Real) (c. 1632–37), Diego Velázquez. © The National Gallery

It’s fascinating to see the Spanish paintings in this way, mined for discrete components and then transformed beyond recognition. This is not how a curator or an art historian – or perhaps an artist with a more fixed visual signature – might look at a painting. Nashashibi, although relatively well-known for her work in film over the past two decades, has only started making paintings in the last five years or so: this is their first museum outing in the UK. Indeed, one of the criteria of the National Gallery’s new residency programme is that its participants be at a ‘formative’ stage in their careers – when they might be more open to different influences and directions prompted by their encounters with the collection. (The Associate Artist programme included big names: the likes of Paula Rego, Peter Blake, Ron Mueck.)

Yet these cryptic and allusive canvases could not be mistaken for the work of an artist-in-training. Rather, there is a strong current of confidence: a willingness to enter into dialogue with some of painting’s greatest masters. As Nashashibi has put it, when discussing her residency with fellow artist Elena Narbutaitė in a conversation published in the catalogue, the process of quoting other artists – or, to use her term, ‘copying’ – is ‘an important process and not just what you do when you don’t know what to do’. It’s ‘related to the idea that you dare to place yourself in a lineage of other artists’. ‘I wouldn’t want to be compared with the old masters’ work. Nevertheless, they lived the life of an artist and did the work of an artist and so do you and I.’

The National Gallery, London, is temporarily closed to the public due to Covid-19 restrictions. For more information on ‘Rosalind Nashashibi: An Overflow of Passion and Sentiment’ (scheduled to run until 21 February 2021) visit the institution’s website.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?