From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The first brutalist building dates, in my opinion, not from the 1950s, has nothing to do with Le Corbusier or the Smithsons and was designed not by an architect but by the mystic, occultist, educationalist and philosopher Rudolf Steiner, a century ago. The astonishing Goetheanum, a monumental sculpted mass of moulded concrete, stands atop a hill a short ride from Basel and still inspires awe. Oddly ahead of its time, unsettlingly cultish, this strangest of 20th-century buildings remains an anomaly, sitting awkwardly outside conventional architectural histories, refusing easy categorisation and foreshadowing modernism.

Steiner (1861–1925) is now mostly known for the child-centred, nature-heavy nurseries and schools he instigated. These are just a fragment of his legacy, which ranges from biodynamic wine and occult medicine to art (his eccentric pairings proved a powerful influence on Joseph Beuys) and dance. But his visionary, at times almost other-worldly architecture has remained a cult.

Never a professional architect, Steiner designed only one major building, though since its first timber manifestation was replaced by this yet more remarkable version, he registers in history for two groundbreaking structures. The Goetheanum was dedicated to the German poet whose ideas about metamorphosis were fundamental to Steiner’s conception of nature; the development from seed to tree were inscribed in his architecture in everything from plan form to a progression of carved capitals.

The first Goetheanum (1913–19), an odd mix of temple, dance hall and conference centre, was a double-domed timber and concrete structure looking like a hilltop observatory. Steiner’s philosophic-religious system, anthroposophy, was intended to be expressed through art and movement; its dance, eurythmy – then a massive fad – was fundamental to its practice. The Goetheanum’s halls, intersecting like a compressed figure eight, were designed to accommodate these theatrical movements; the dome of the first building was a garish multi-coloured globe, as if the heavens were awash in a dancing spectrum. That building burnt down, mysteriously, in 1922. Steiner immediately set about designing a more ambitious, more solid structure. Even before it was completed – in 1928, three years after he died – it became a sensation. Visiting architects were awed by this radical structure shrouded in complex scaffolding, its emergent form visible within.

The second Goetheanum building in Dornach, Switzerland, designed by Rudolf Steiner after the first Goetheanum burnt down in 1922, and completed in 1928. Photo: Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

This second Goetheanum is a sculptural mass, almost topographical or geological in nature, seemingly moulded – which was how Steiner designed, pressing, squeezing and carving a piece of clay in his hands until he felt he had the form he desired. He wanted it to appear to grow from the landscape, and to appear literally to be growing, thus encouraging inner change in its users. Steiner rejected right angles as unnatural, constricting body and mind. The result veers between grotto and cathedral, a building of surprising energy and power, with curiously shaped windows and theatrical, brutal-baroque staircases in heavily formed concrete. Steiner’s kitsch colours wash the ceilings of the performance spaces, naive painted surfaces softening the heavy material.

The architecture does not end at the Goetheanum: the site is a kind of campus, a centre for anthroposophy, Steiner’s riposte to theosophy, Helena Blavatsky’s occult- inflected proto-New Age movement. There are residences and utilities, all in this expressive concrete manner. The best of them is the ‘Hothouse’, the boiler room built for the complex in 1914, with its plume of concrete smoke branching out towards the sky like a tree. One of the best buildings of its era, it is an example of architecture parlante, a thing that speaks of what it is through its form. Steiner himself denied his architecture was symbolic; rather, it was an expression of inner forces and movements.

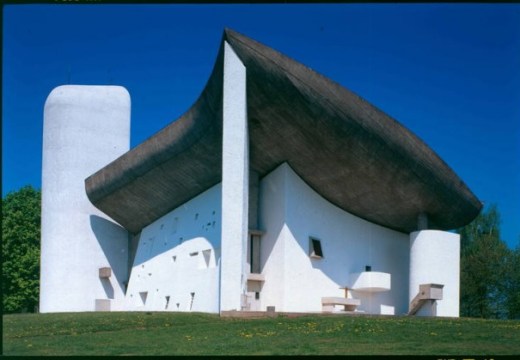

The Goetheanum still stands on that hill, solid and oddly indeterminate. It can be difficult, sometimes, to tell whether this is a building from the 1950s or the 1970s, or one recently completed. A walk through the interior and the site is a tour of a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art in which everything from the radiator covers and door handles to the handrails and benches has been given serious consideration as a part of the whole. Its wider influence is indirect and obscure. Steiner was such a strange figure, and so clearly set apart from the wider architectural culture, that many of the architects who visited – including Frank Lloyd Wright, Frank Gehry and Hans Scharoun (the latter the architect of the wonderful Philharmonic Hall in Berlin) – were profoundly impressed and admitted to being so. But it is Le Corbusier (cagey about any direct inspiration) who, I’d suggest, was influenced most, even if he was loath to admit it. Corb, who was born in La-Chaux-de-Fonds on the Swiss-French border, must surely have been aware of the Goetheanum. When he underwent his conversion from the crisp functionalism of his 1920s villas to the sculptural concrete of his church of Notre-Dame-du-Haut at Ron- champ he adopted a style which seems to me very akin to Steiner’s.

Both buildings signified an attempt to move from architecture as utility to building as expressive, transformative and sacred space, pregnant with art and meaning. Both men put themselves forward as gurus, publishing endlessly on how building could enhance life and embody natural forces, and both adapted mass concrete as the expressive material of the architect as sculptor. But, in a way, I find Steiner more interesting. He can be seen as a one-off, a dead end, or he can be seen as one of the more occult figures in an early modernism ripe with weird theories and strange magic, alongside shaven-headed, raw-garlic-eating Johannes Itten, the esoteric cult of Mazdaznan and the early spiritual Kandinsky. He can also be seen as a foundational figure in all kinds of subsequent movements, from brutalism through to the organic architecture of Imre Makovecz and his followers in Hungary in the late 20th century.

Steiner’s haunted concrete Goetheanum is a strange attractor, still emanating eccentricity and still exerting a gravitational pull. It is one of modernism’s oddest untaken paths, a possible future from a parallel universe.

From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home