‘“Come,” said my friend Professor Omnium, one clear morning, “let us take an excursion round the world! […] Go round the world with me here in London.”’ So wrote Moncure Daniel Conway in his Travels in South Kensington with Notes on Decorative Art and Architecture in England (1882) describing the wondrous range of the V&A’s Architectural Courts. Our first director, Henry Cole, was more sedate as he described their opening. ‘New Architectural Court opening in Evening. Generally much approved,’ he noted in his diary for 10 July 1873.

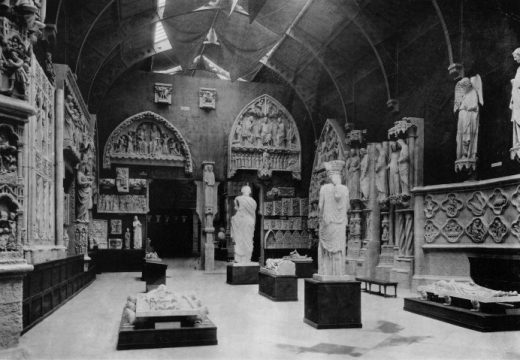

With their garish mix of Spanish porticos and Florentine gates, Michelangelo sculptures and Anglo-Saxon crosses, the Cast Courts have long been fundamental to the V&A. I got to know them intimately when abseiling down the interior of Trajan’s Column: behind the expertly laid plaster cast is a circular Victorian brick chimney – with an awful lot of South Ken soot built up over the decades.

Cast of the Pórtico de la Gloria, from the original 12th-century portico at the Cathedral

of Santiago de Compostela (detail; 1866), cast by Domenico Brucciani. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Like all V&A aficionados, I adore these rooms. And this December our restoration programme culminates in the opening of the Ruddock Family Cast Court and the Chitra Nirmal Sethia Gallery. In addition to extensive conservation and reinterpretation, the restoration for the first time allows the visitor to sit inside the base of Trajan’s Column, meditating on the fall of Rome.

From the outset, the plaster casts inspired conflicting responses. In 1873, the Builder magazine compared a first sight to a glimpse of Mont Blanc, creating one of those ‘impressions that can scarcely be effaced’. The Times, by contrast, noted in 1882 ‘the most extraordinary jumble of works’ at South Kensington, particularly in comparison with the more orderly displays of casts at the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Berlin. Today, a similar confusion arises as visitors wrestle with the meaning of these eerily accurate reproductions: are they real? Shouldn’t David be in Florence?

The Cast Courts trace the formation of the South Kensington Museum. In 1837 the Government School of Design acquired a collection of ‘casts of ornamental art of all periods and countries’ for teaching purposes. But it was Cole who, as director of the new Museum of Manufactures, as the V&A was originally called, took over and transformed the collection. His abiding admiration for the marriage of science and art, historicism and modernism, led him to build a photography studio and start collecting electrotyping. Then in 1867 he launched his ‘Convention for Promoting Universally Reproductions of Works of Art for the Benefit of Museums of all Countries’, which heralded a new era for the exchange and production of plaster casts across Europe.

Along with the admiration for technology came a strong belief in access. The South Kensington Museum had pioneered gas lighting for evening openings and cafés for family visitors: in the same spirit, the Cast Courts would allow working people to see the architectural highlights of Western civilisation without crossing the channel. It was a superb mid Victorian mix of populism, scholarship and democracy.

Sadly, in the interwar years, the anti-Victorian ethos saw plaster cast copies fall crashingly out of fashion. A large part of the V&A’s collection was dispersed, even smashed up – particularly the non-European fragments – and the Cast Courts were condemned as an embarrassing assemblage of fakes.

Cast of an aegicrane capital, from a 16th-century stone pilaster capital in the Tuileries Palace, Paris (19th century), probably made at the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

No longer. In today’s era of 3D printing and digital surrogacy, artists and designers are finding renewed inspiration in our casts; students and scholars are studying their craftsmen; and many of our copies exist where the original is lost or damaged. V&A casts from the 16th-century Tuileries Palace are now the only surviving three-dimensional evidence of the original, and while Rome’s Trajan’s Column has suffered greatly from pollution, our own cast retains much of the actual monument’s now-lost detail. Embracing high-definition photography and scanning technologies, museums are producing millions of digital files for public use. But the Cast Courts were the first conscious attempt to reproduce and share the canon.

Professor Omnium’s ambition has now been widely realised: you can travel the world on your smartphone. But there remains something precious about the original fake. In our epoch of relentless reproduction, when so many experience great art first as a copy – a photograph, a digital image, in a film – the authentic has acquired new potency. We want our visitors to understand that these sublime monuments are facsimiles, while valuing them also as 19th-century sculptures moulded by highly skilled hands.

Without rehearsing the trace and the aura, the new V&A Cast Courts might indicate we have reached peak Walter Benjamin: a truly authentic restoration of fakes.

Tristram Hunt is director of the V&A. The Ruddock Family Cast Court and

the Chitra Nirmal Sethia Gallery open on 1 December.

From the November 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home