From the October 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

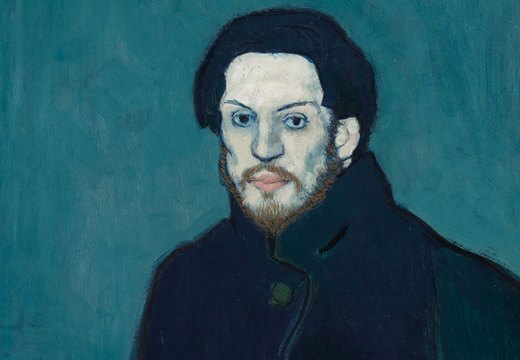

A morning discussing death can be surprisingly upbeat, if the discussion is with Sophie Calle. I am meeting her in late July at the Musée Picasso in Paris, where she is in the middle of installing her new exhibition, ‘À toi de faire, ma mignonne’ (It’s up to you, my darling), which opens this month (3 October–7 January 2024). The artist is taking over all four floors of the museum, partly responding to Picasso’s work as part of the events to mark the 50th anniversary of his death – but also taking stock of her own life and projects both realised and shelved. Death is the show’s dominant subject, as it has been in Calle’s work since she started out in the 1970s. ‘I have always walked around cemeteries,’ she tells me. ‘I am one of those people who goes to funerals.’ While such a marked interest in death might seem morbid, Calle’s art is anything but.

Installation view of Sophie Calle’s exhibition ‘MAdRe’ at Castello di Rivoli, Turin, 2014–15. Photo: Renato Ghiazza; © Sophie Calle/ADAGP, Paris 2023

At the Musée Picasso, Calle is clearly thinking about her own final act. Among the items on display is an obituary she commissioned and the coffin she has picked out for herself. While many artists have been given carte blanche in august institutions before, few have moved in their belongings. Calle has emptied her entire house in the Paris suburb of Malakoff, where she has lived for 40 years, next door to the artists Annette Messager and the late Christian Boltanski (they all moved there in the 1980s for cheaper rents and large studio spaces). She created an inventory of every object and piece of furniture, down to the last chair, then selected some to appear on display in the museum and put the rest into storage. For the duration of the show she will stay in a hotel. So here is Calle’s piano, scores of photographs and other objects, including the neck and head of Monique, a taxidermied giraffe named after Calle’s mother, who has featured in many previous installations and venues. She has grouped a selection of the artworks she has collected over the years – drawings, photos, texts, soft toys – in what she calls ‘my Guernica’, appearing on the ground floor of the museum. This work covers exactly the same surface as Picasso’s original – 27.0824m2 according to one of the exhibition catalogues – and among the items is my favourite: a small embroidered message by Annette Messager: ‘Better to be married than dead.’

The reason Calle has gone to such lengths with her own belongings is to explore the practical side of death, and specifically what we do with our things once we have gone. This is, she tells me, ‘perhaps the most annoying thing to have to sort out: what comes afterwards.’ I raise the subject of children, but my choice of words is unfortunate: ‘So the lack of children in your life…’ Immediately she corrects me. ‘It’s not a lack. It’s everything but!’ She is smiling, but I can tell she’s deadly serious. Celebrating the fact that she does not have children has been a constant in the artist’s work. She does, however, admit that there is perhaps one advantage to having them. ‘Clearly people with children have absolutely no questions to ask themselves about their will and testament. It’s all sorted out, unless they hate them or something […] if I had kids, I would let them deal with things themselves, which is not necessarily a gift.’

Sophie Calle photographed in the Musée Picasso in Paris in July 2023. Photo: Yves Géant

Several times during our conversation Calle jumps up from her seat and goes over to direct the museum staff working at large tables and hanging items on the walls. Given the concerns of the new show, I ask if her relationship with death has changed over the years. ‘I go to more funerals these days, I lose more close friends,’ she says. But while actual deaths are all around, the only real shift, she says, is a greater awareness of time passing. ‘When someone suggests that I do something I ask myself, do I have time? For example, my being here – I’m taking stock in a way, I’m doing the housekeeping, so I ask myself, what will I do after this?’ Does death scare her? Not yet. ‘I think of it peacefully because today I have no reason not to. There is no sword hanging over my head. Maybe the day there is one I’ll not be so peaceful and all my games won’t be of any use to me any more.’

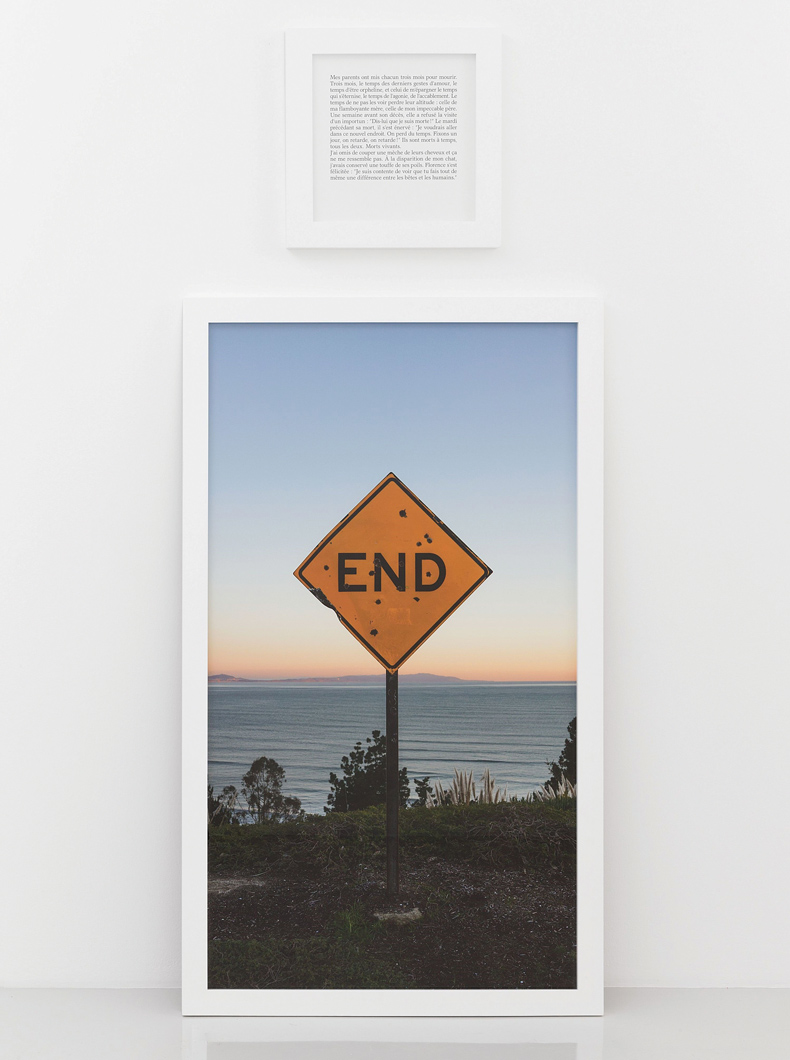

Souris (Mouse) (2017), Sophie Calle. Photo: courtesy the artist and Perrotin; © Sophie Calle/ADAGP, Paris 2023

Calle has been playing her ‘games’ for a long time. In, for example, Les Tombes (1990), a striking series of black-and-white photographs taken in cemeteries of tombstones with generic engravings (‘mother’, ‘father’, ‘my dear husband’). Then again in the installation Rachel Monique (2007–14), which concerns the death of her mother. It includes the short film Pas pu saisir la mort (Couldn’t catch death), screened at the Venice Biennale in 2007, in which Calle recorded her mother’s dying moments. In 2018 she published a book of photos again from cemeteries, titled Que faites vous de vos morts? (What do you do with your dead?). The same year, to commemorate the death of her beloved cat Souris (French for ‘Mouse’) she assembled the multimedia homage Souris Calle, which included photographs of the artist simulating pregnancy, using body props to suggest that she was carrying the cat in her womb. Calle also crafted a coffin for the now taxidermied puss, who we see lying peacefully swaddled. All this, she tells me, is ‘a way of exorcising’ a potentially terrifying prospect. Filming her mother dying, for example, ‘helped me more than it weighed me down, because all of a sudden we had a project together’. The camera was a way of maintaining a connection between them even when Calle was not physically there to look through the lens.

While Calle’s work shares some similarities with her Malakoff neighbour Messager – most notably a love of taxidermy – a key difference is how she tends to put her- self at the centre of her works. She generally starts from a personal experience and then draws in other people, often friends, but frequently strangers. For her first major work, Les Dormeurs (Sleepers) of 1979, Calle invited people to sleep in her bed and documented it in writing and photographs. A year later for Suite Vénitienne (Venetian Suite) she slipped on a blonde wig and followed a man she had never met from Paris to Venice, recounting the whole adventure in photos. One ex-boyfriend provided the inspiration for Prenez soin de vous (Take care of yourself) of 2004–07, the title of the work taken from the last line of the email he wrote breaking up with her. Unsure how to react to an unceremonious dumping, Calle asked 107 women to read the email and respond in their own ways, making a show from their answers that ranged from dances and songs to a crossword puzzle.

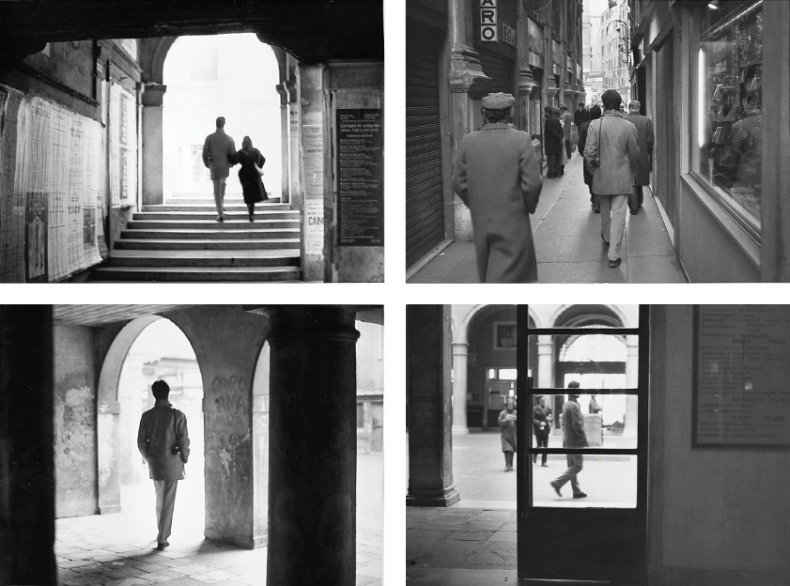

Suite Vénitienne (detail; 1980) by Sophie Calle. ‘I followed strangers on the street. For the pleasure of following them. At the end of January 1980, on the streets of Paris, I followed a man whom I lost sight of a few minutes later in the crowd. That very evening, quite by chance, he was introduced to me at an opening. During the course of our conversation, he told me he was planning an imminent trip to Venice. So I decided to follow him.’ Photo: © Sophie Calle/ADAGP, Paris 2023

For an exhibition last year called ‘Les fantômes d’Orsay’ (The Ghosts of Orsay), the inspiration was not a person, but a place. In 1978, she first discovered the abandoned Grand Hôtel Palais d’Orsay, next to the derelict station. Over the course of repeated visits, Calle found and took away reminders of its former occupants. Dusting off these mementoes gave her the basis of the show at the Musée d’Orsay, into which the hotel had been absorbed. The presentation was typical of Calle – an engrossing mystery presented through a series of photographs of the location, full of signs of its former life. Among the items she had assembled were scraps of paper covered with notes addressed to a certain ‘Oddo’, presumably the hotel janitor, requesting he deal with various problems (a water leak on floor six, a faulty toilet, no hot water) and objects such as kitchen utensils or door parts. Calle added texts of her own, imagining what these former occupants were like and guessing, playfully, what the found objects were for. Her description of a door knob and its metal frame, for example, began: ‘Ancient weapon of unknown origin. There is, indeed, no other reasonable explanation for this heavy blunt metallic object.’

The difference between the basic function of everyday objects and what they mean to us is something Calle also explores at the Musée Picasso. In the mock-catalogue of the contents of her house, a dry description of each item is accompanied by a personal comment. Her piano, for example, is listed as a musical instrument 1.2m in length, but it is also a ‘silent piano’ that she has never played but always wanted to master, which sat in her home as a promise of self-betterment. In a real auction catalogue, of course, a would-be buyer would never know what an object meant to its previous owner.

My Mother, My Cat, My Father (2017), Sophie Calle. Photo: courtesy the artist and Perrotin; © Sophie Calle/ADAGP, Paris 2023

I ask what she intends to do when the exhibition ends: will she just put everything back as it was? ‘Honestly I have no idea.’ When the removal team turned up and started to take everything away, did she have any doubts? Definitely: ‘I thought what on earth am I doing? But it was too late.’ She says this as we stand in front of her ‘Guernica’ and watch the last artworks being hung. One piece is very heavy and takes three people to lift it up to the wall. ‘Rather them than me,’ she whispers, before leaping forward to adjust its position by a fraction. To our left, the calligrapher Julien Chazal is drawing the outlines of a few larger works of art Calle had wanted to include, but which proved too difficult to incorporate. Chazal is also writing all the titles and texts that appear on the walls of the show, in a beautiful script with quill pen. The writing adds to the air of an amateur sleuth at work.

Calle tells me that the death of her father in 2015 was a real shock, plunging her into doubt about making art. Bob Calle, a cancer specialist who was also an art collector, founded the Carré d’Art museum in Nîmes. He was Calle’s ‘first gaze’ as she puts it, and the reason she became an artist in the first place, seeking his attention and praise. ‘I asked myself if I shouldn’t stop it all,’ Calle says, ‘because for a brief moment I had this thought of wanting him to have seen everything.’

When the Musée Picasso first asked Calle to take over the museum, she says she hesitated, ‘Because I mean, it’s Picasso, he’s a very overwhelming presence… he’s huge!’ One way she dealt with this can be seen in a set of rooms on the ground floor that includes several large photographs on walls where paintings normally hang. The photos show the paintings – but they are all covered in paper. The famous bronze goat is also wrapped and sealed with masking tape. Alongside the paintings there are also ‘phantoms’ – palimpsest images of various works that were out on loan when Calle visited, including Paul Drawing (1923) and Large Bather with Book (1937). Overlaying reproductions of these works are descriptions of the absent paintings by staff at the museum.

Tu les as bien eus! (You got them!) (2018), Sophie Calle. Private collection. Photo: courtesy the artist and Perrotin; © Sophie Calle/ADAGP, Paris 2023

Engaging with Picasso without having him in the room is also Calle’s way of dealing with what she calls her ‘imposter syndrome’, which she explains to me with one of her favourite anecdotes: ‘When I exhibited at MoMA next to the Magrittes and the Hoppers, and [my mother] told me “You really fooled them”, as though I had managed to sneak my way in.’ (The story has also turned into an artwork.) This was in 1992 and it was Calle’s first major exhibition outside France. I ask if her imposter syndrome has gone away now and she says yes, but it’s not that simple – it returns every once in a while, as it did when she got the invitation from the Musée Picasso. ‘Straight away I imagined [my mother] telling me, “Aren’t you scared? Aren’t you ashamed? Why you?” I imagined her bursting out laughing and telling me: “Well, that just takes the biscuit!”’

Calle enjoys telling that story about her mother’s incredulity at her success: self-deprecating manner notwithstanding, she is probably the most famous contemporary artist in France. As I am about to leave, with the ‘Guernica’ installation complete and several members of the museum’s staff calling for Calle’s attention, I ask her what she thinks Picasso would have made of all this. The title of the show is partly an answer, she says. She took it from the French translation of a 1941 thriller in the Lemmy Caution series by Peter Cheyney. She imagined Picasso observing her and saying the phrase – over to you: let’s see what you’re made of. And is his gaze benevolent or critical? ‘I decided it would be benevolent,’ she says. ‘I don’t want to come and squat in a hostile place. Maybe it wouldn’t make him laugh at all that I’m here, but there you go.’

‘À toi de faire, ma mignonne’ is at the Musée Picasso, Paris, from 3 October–7 January 2024.

From the October 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home