‘Ideas aren’t real estate,’ Robert Rauschenberg told Time magazine in 1976. ‘They grow collectively and that knocks out the egotistical loneliness that generally infects art.’ Collaboration was both a method and a principle for the artist, from his work over many decades with the choreographer Merce Cunningham to his support for cooperative projects such as Experiments in Art and Technology in the late 1960s and the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange some 20 years later. And the possibilities of appropriation were fundamental to much of his work – just think of Currents, a 16 metre-long screenprint of newspaper clippings from the first months of 1970. Rauschenberg understood how images and works of art can themselves participate in collaborations.

It is in keeping with the artist’s own processes, then, that the Rauschenberg Foundation has recently announced a fair use image policy that will transform how art historians are able to interpret and disseminate images of the artist’s work. And not only that: it is a decision that ought to recalibrate attitudes to this aspect of copyright more widely. The Foundation is to cease claiming royalties and issuing licences for ‘non-commercial, scholarly, and/or transformative purposes, such as: creative writings; print and digital newspapers and magazines; online teaching tools and study guides; social media; and transformative use in artworks’.

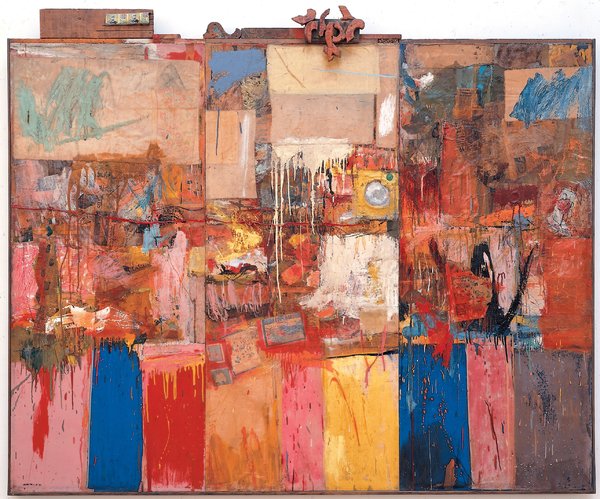

Collection (1954), Robert Rauschenberg. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Gift of Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson

Images will not only be freely available to specialists but to the general public – and so to anyone with a Twitter or Instagram account, who may frequently publish images online with little if any consideration of intellectual property law. Indeed, it is the proliferation of images on social media, and across the internet more generally, that has provoked the Rauschenberg Foundation’s brave and brilliant decision. There are now so many poor-quality images of artworks available online – badly shot or lit, and often accompanied by inaccurate information – for the Foundation to be concerned about their impact on Rauschenberg’s legacy. These days, researchers or teachers often use inadequate images to avoid spending time and money on licences; publishers may choose not to illustrate certain works or may even avoid commissioning specific articles due to the sometimes prohibitive costs of clearing copyright.

The Rauschenberg Foundation is to be commended for what is a vast gesture of goodwill. As its CEO Christy MacLear told me, ‘scholars, writers and independent curators should never be saddled with copyright clearance costs because they’re our best stewards […] We want to embolden and authorise the people who are our advocates.’ And this is goodwill not only because of how the new policy will eliminate red tape and lead to the Foundation renouncing significant royalties, but because it reaffirms trust in the very people who want to explore, debate and promote Rauschenberg’s legacy.

This decision is at once realistic and idealistic (in the best possible sense), acknowledging that the old way of doing things is defunct in the digital age and setting an example for other artists’ estates and foundations to follow. Too many of these seem set not on fostering an artist’s legacy, but on sponging up revenue for their heirs. Even worse are those that try to direct how artworks are studied and interpreted – effectively a type of intellectual censorship that arises when estate holders demand to approve a publication before they will release print-quality images of artworks. At Apollo we have had to counter demands from artists’ estates or custodians that we reword critical opinions on several occasions in the past 12 months.

It is unnerving to be held to ransom in this way, and against all principles of journalistic, scholarly and editorial independence. Art historians should be free to write about artists and artworks with the utmost intellectual freedom. The Rauschenberg Foundation’s pioneering attitude to fair use is a reminder that art criticism and scholarship should themselves be collaborative pursuits, and not a series of skirmishes to be had with artists and their keepers.

From the April issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Three cheers for Bob Rauschenberg!

Rauschenberg in his Front Street studio, New York, 1958. Photo: Kay Harris

Share

‘Ideas aren’t real estate,’ Robert Rauschenberg told Time magazine in 1976. ‘They grow collectively and that knocks out the egotistical loneliness that generally infects art.’ Collaboration was both a method and a principle for the artist, from his work over many decades with the choreographer Merce Cunningham to his support for cooperative projects such as Experiments in Art and Technology in the late 1960s and the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange some 20 years later. And the possibilities of appropriation were fundamental to much of his work – just think of Currents, a 16 metre-long screenprint of newspaper clippings from the first months of 1970. Rauschenberg understood how images and works of art can themselves participate in collaborations.

It is in keeping with the artist’s own processes, then, that the Rauschenberg Foundation has recently announced a fair use image policy that will transform how art historians are able to interpret and disseminate images of the artist’s work. And not only that: it is a decision that ought to recalibrate attitudes to this aspect of copyright more widely. The Foundation is to cease claiming royalties and issuing licences for ‘non-commercial, scholarly, and/or transformative purposes, such as: creative writings; print and digital newspapers and magazines; online teaching tools and study guides; social media; and transformative use in artworks’.

Collection (1954), Robert Rauschenberg. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Gift of Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson

Images will not only be freely available to specialists but to the general public – and so to anyone with a Twitter or Instagram account, who may frequently publish images online with little if any consideration of intellectual property law. Indeed, it is the proliferation of images on social media, and across the internet more generally, that has provoked the Rauschenberg Foundation’s brave and brilliant decision. There are now so many poor-quality images of artworks available online – badly shot or lit, and often accompanied by inaccurate information – for the Foundation to be concerned about their impact on Rauschenberg’s legacy. These days, researchers or teachers often use inadequate images to avoid spending time and money on licences; publishers may choose not to illustrate certain works or may even avoid commissioning specific articles due to the sometimes prohibitive costs of clearing copyright.

The Rauschenberg Foundation is to be commended for what is a vast gesture of goodwill. As its CEO Christy MacLear told me, ‘scholars, writers and independent curators should never be saddled with copyright clearance costs because they’re our best stewards […] We want to embolden and authorise the people who are our advocates.’ And this is goodwill not only because of how the new policy will eliminate red tape and lead to the Foundation renouncing significant royalties, but because it reaffirms trust in the very people who want to explore, debate and promote Rauschenberg’s legacy.

This decision is at once realistic and idealistic (in the best possible sense), acknowledging that the old way of doing things is defunct in the digital age and setting an example for other artists’ estates and foundations to follow. Too many of these seem set not on fostering an artist’s legacy, but on sponging up revenue for their heirs. Even worse are those that try to direct how artworks are studied and interpreted – effectively a type of intellectual censorship that arises when estate holders demand to approve a publication before they will release print-quality images of artworks. At Apollo we have had to counter demands from artists’ estates or custodians that we reword critical opinions on several occasions in the past 12 months.

It is unnerving to be held to ransom in this way, and against all principles of journalistic, scholarly and editorial independence. Art historians should be free to write about artists and artworks with the utmost intellectual freedom. The Rauschenberg Foundation’s pioneering attitude to fair use is a reminder that art criticism and scholarship should themselves be collaborative pursuits, and not a series of skirmishes to be had with artists and their keepers.

From the April issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

The modern mysteries of Michaël Borremans

The Belgian painter reveres the Old Masters but is ‘ashamed’ by the state of figurative painting today

Could the mystery of Nefertiti’s tomb soon be solved?

Art News Daily : 17 March

Paris’s celebration of Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun is long overdue

A memorable exhibition at the Grand Palais tells the story of a remarkable artist and independent woman