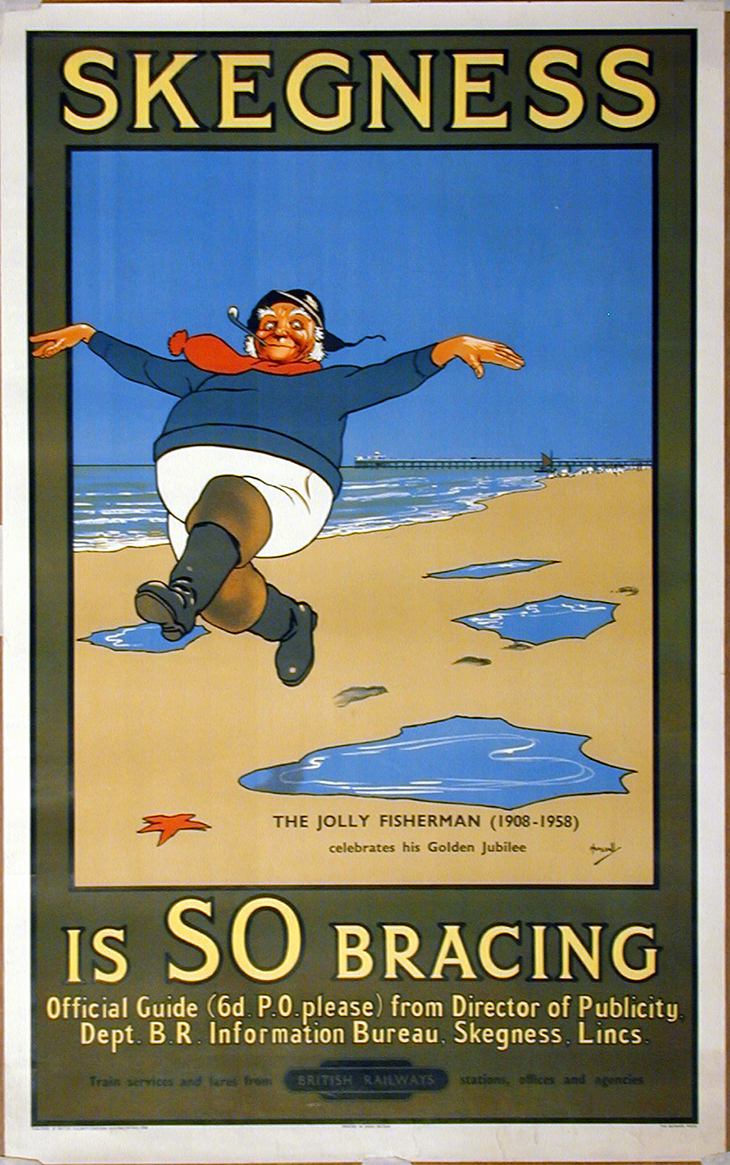

In his heyday in the period before the First World War, the versatile British artist John Hassall (1868–1948) was often referred to as ‘the Poster King’. Hassall also produced illustrations, postcards and various other kinds of applied design but nowadays, as Lucinda Gosling acknowledges in her account of Hassall’s life and work, he is mostly remembered for his poster Skegness is So Bracing, commissioned by the Great Northern Railway to promote the Lincolnshire resort. The figure of the jolly fisherman on the beach established a spirited and enduringly popular icon for the English seaside. Although it was not the first of Hassall’s travel posters, it was the design where subject, humour and design combined most successfully and memorably.

Skegness is So Bracing (1958), based on the original of 1908 by John Hassall. Courtesy Unicorn Publishing

To be crowned the ‘Poster King’ at that time was no mean achievement. The field was crowded with talented designers. Gosling describes how, at the end of the 19th century, the poster emerged as a new kind of image, made to be seen from a distance and while the viewer was on the move; an image rooted in the experience of modern life and of its restless mechanical acceleration. Through a combination of hard work, personality and professional association, Hassall successfully established himself at the very centre of the new image-machine. And Lucinda Gosling positions his posters as the foundation of what was often referred to as ‘the poor man’s picture gallery’.

Hassall’s early hopes, however, had been mostly for adventure. When he failed the military examinations for Sandhurst, he and his brother emigrated to Canada in 1888, to become farmers. It was from there that his first drawings and illustrations were accepted for publication by The Daily Graphic in London. The possibility of working as a commercial artist seemed, in contrast to the farm, both exotic and reassuringly comfortable. Hassall left Canada to pursue his artistic vocation. He studied in first Antwerp and then Paris during the early 1890s, during which time he became familiar with the poster as an expression of a culture that combined visual sophistication and democratic appeal.

A Night Out (1896), poster for the Vaudeville Theatre by John Hassall. Courtesy Unicorn Publishing

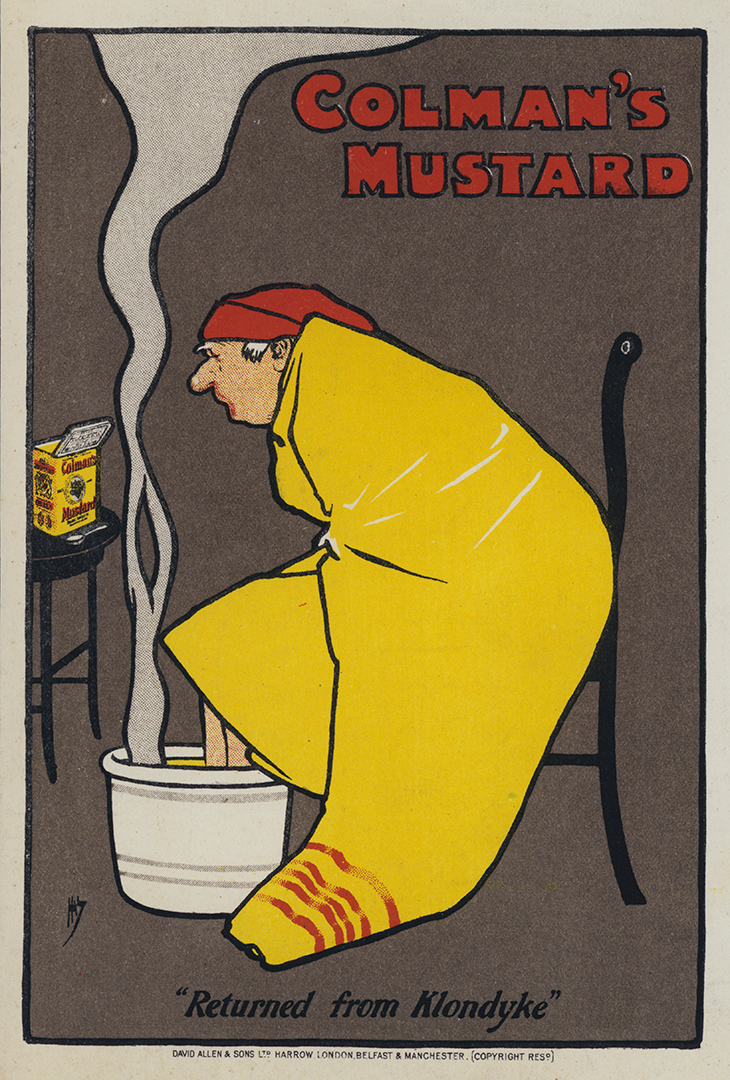

Upon his return to London, Hassall began to work for the Sketch and in 1896 he began an association with the commercial advertising printers David Allen & Sons. David Allen was one of the largest of the advertising printing companies in Britain, with offices in Belfast, London and Manchester, along with an outpost in New York. The firm had secured a substantial number of the theatrical poster and advertising accounts and had developed into a company that also managed the distribution and display of advertising material throughout Britain. The firm also provided stock posters for touring theatrical troupes. Hassall’s association with David Allen gave him a national platform that allowed his work to be more widely seen, and to better advantage, than would have otherwise been possible.

One of John Hassall’s advertisements for Colman’s of Norwich from 1898–89. Courtesy Unicorn Publishing

Hassall’s posters are immediately recognisable through their combination of flat-colour and figure drawing. The abstractions of flat colour, deriving from Japanese woodblock prints, were softened and made recognisable by the ligne claire style of drawing. The implied illumination of the flat colours was as ideal for the rendering of theatrical posters as for the open skies of the seaside.

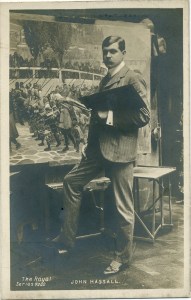

John Hassall, photographed in his studio in 1909. Courtesy Unicorn Publishing

The designer’s theatrical associations made him a celebrity in London life, and he became a favourite with society journalists. His flamboyance was legendary, as was his lifelong enthusiasm for fancy dress, japes and extravagant parties; he was the perfect example of a bohemian Edwardian artist. After the First World War, his fortunes declined somewhat as his graphic style was superseded and his extravagant lifestyle became increasingly unsustainable.

Gosling combines biographical detail with enough background and context to convince us that Hassall was an important transitional figure in the shift of visual culture from Victorian fussiness to the more dramatic and dynamic simplifications of modern advertising. This is a valuable and important addition to the bookcase of anyone interested in the history of British poster design.

John Hassall: The Life and Art of the Poster King by Lucinda Gosling is published by Unicorn Publishing.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?