Built into the skirting board in Helen Ede’s bedroom at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge is a small hatch that opens into a cabinet in her husband Jim’s bedroom below. ‘It fascinates me,’ says Linder, crouching down to get a better look while the rest of us – here for a preview of her exhibition in the galleries at Kettle’s Yard, which leaks into the couple’s former home – stand by and watch. ‘Perhaps it was a way for them to communicate.’ She might be right, but for now the hatch has another function: a volume control for Linder’s new audio installation composed of women reciting slang words for female sexual organs in Urdu, Spanish, Mandarin and other languages. The artist’s aim with this and her other interventions here – or ‘house guests’, as she calls them – is to flesh out the lives of women like Helen Ede, whose presence in the house so carefully curated by her husband is largely invisible. There are tributes to female saints and martyrs and the artist Barbara Hepworth, among others.

In her art, Linder tussles with the stories we choose to tell. Born Linda Mulvey in Liverpool in 1954, she emerged with her ambiguously gendered moniker in the Manchester punk scene in the 1970s. The galleries adjacent to the house open with her most well-known works from that period. ‘By this point I was bored by my own art-making,’ says Linder, who had spent her childhood drawing and painting. When she turned to photomontage – swapping her bulky paint pots and brushes for a scalpel – it was a relief. ‘Now I had one instrument, which liberated my practice.’

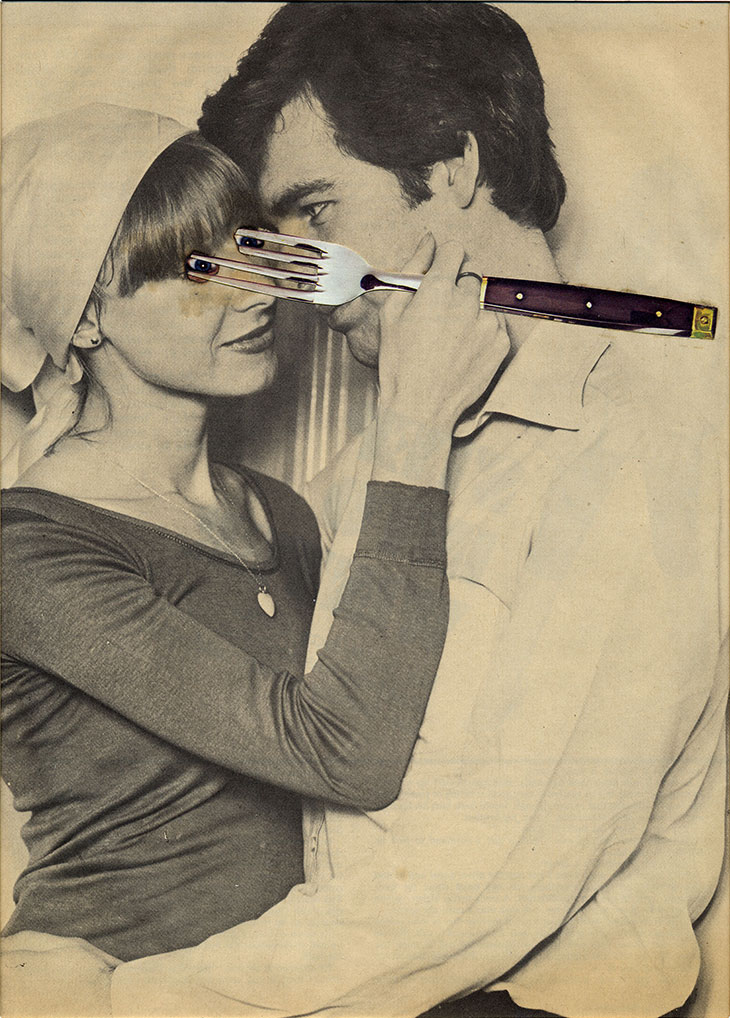

Untitled (1977), Linder. Courtesy the artist; Modern Art, London; Dépendance, Brussels; Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm, Paris; Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, New York, Tokyo; © Linder Sterling

Dating from 1976–78, her earliest photomontages feature an explosion of imagery. There’s that oily female nude with the Morphy Richards iron for a head that appeared on the sleeve for the Buzzcocks’ single ‘Orgasm Addict’. A bowl of lettuce leaves and sliced cucumber tossed with toothy grins and eyes with spidery lashes. A pair of TV-headed lovers whose genitals have been replaced by a vacuum cleaner and a remote control. Inspired by the pre-war montages of Dadaists such as John Heartfield and Hannah Höch, Linder pilfered from the world around her – lifting contemporary imagery from men’s and women’s magazines and juxtaposing it on the page. The result: a heady mix of soft porn and domestic tat.

She had been reading things like Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch and the feminist magazine Spare Rib, and wanted to create art that challenged ideas about women, sex and gender. The resulting work crackles with a dark energy that can be hard to handle. A man embraces a woman while she stabs a fork in her eyes. In lieu of freckles, a girl’s face is pitted with cigarette burns. ‘I was the lucky one,’ says Linder, mentioning the prevalence of self-harm among her friends at the time. ‘I had somewhere to take all the free-floating anxiety, the not-knowingness. I could make my mark with it.’ One such mark was made on bonfire night in 1982, when she and her post-punk band Ludus performed at the Haçienda in Manchester. Video footage shows the artist singing in a dress made from chicken flesh, which she rips off to reveal a black strap-on dildo. A fierce act of retaliation against the city’s macho culture, and her last performance until 2000.

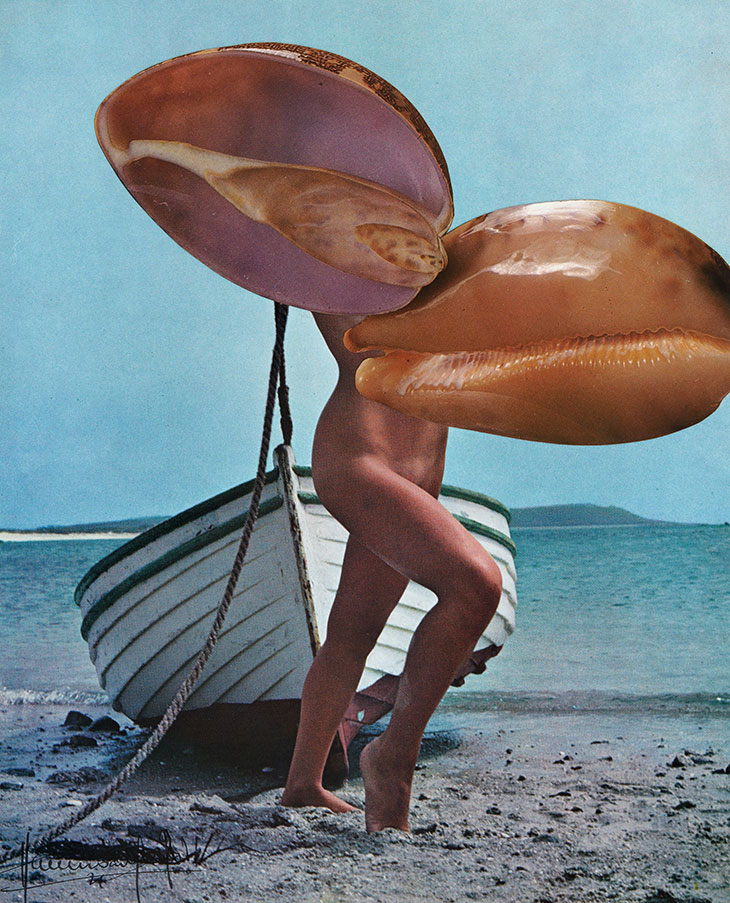

The Goddess Who Has Five Faces (2019), Linder. Courtesy the artist; Modern Art, London; Dépendance, Brussels; Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm, Paris; Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, New York, Tokyo

Linder also stopped making photomontages in the 1980s – after all, it was the end of the British underground – and only restarted in earnest in 2006, after a musical stint in Brussels and becoming a mother. The more recent works are presented in a second gallery space, marking a clean break between these two phases of her career, as frustration and disappointment give way to pleasure and reclamation. The Goddess series (2019) features swirling shells and tender flowers pasted on black-and-white and colour nudes shot by Harrison Marks, the nude photographer-cum-pornographer. The effect is seductive yet slightly eerie. Then there’s Glorification de l’Élue (2011), a blown-up photograph inspired by a magazine called Splosh! that took as its subject the messy fetish of bathing a body in various foodstuffs. The queasy large-scale portrait shows a woman dripping with custard, rice pudding and food colouring. ‘It was a hot July day so you can only imagine the sickly-sweet smell,’ says Linder.

Glorification de l’Élue (2011), Linder. © Modern Art

Back in the house is a more appealing scent: Linder has recreated the potpourri that Jim Ede made for his and Helen’s home. The exhibition also extends up the stairs above the galleries, with a refashioning of The Bower of Bliss (2018), a luscious mural Linder created at Southwark station for Art on the Underground. Her work spills into the neighbouring St Peter’s Church too, where you’ll discover the third iteration of Salt Shrine (first shown in 1997) – a whopping pile of salt that, Linder tells us, once prompted someone to ask, ‘Is this an installation or has something happened?’

Kettle’s Yard is the kind of the place that reveals more of itself to you every time you visit. ‘There are so many myths and mysteries here,’ says Linder. ‘I’ve created “guests” who sit in the house and learn from it, as well as expand on it.’ Much like her trademark photomontages, then, which pull apart narratives and create new ones when – in beautifully disparate ways – they’re put together again.

‘Linderism’ is at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, until 26 April.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

What Frank Stella saw – and what he made us see