On 6 September 1620, 102 passengers and a crew of around 25–30 set sail on the Mayflower from Plymouth. It was over two months until they sighted land: the curved promontory on the east coast of North America today known as Cape Cod. The rest, as they say, is history. As Plymouth gears up for the 400th anniversary of the ship’s departure in 2020, this history takes on a local focus, informing how the city defines its present character, and envisages possible futures.

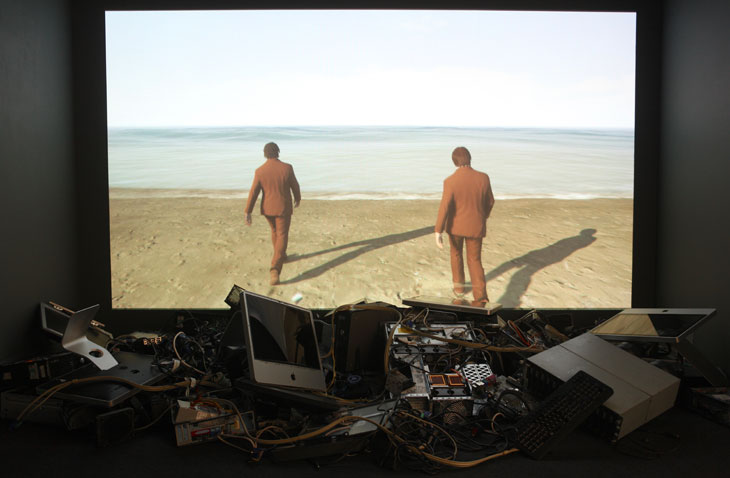

Something of this is reflected in Finding Fanon (2015–17), a triptych of films by artists Larry Achiampong and David Blandy currently on view at Plymouth Arts Centre (until 2 September). The films have been created using the engine behind computer game Grand Theft Auto: we see avatars of the artists swimming, falling through the air, and traversing the game’s vast cityscapes. Disembodied narrations by Hayleigh-Joy Rose address histories of immigration, exploitation, race, and colonialism, informed by the work of activist-writer and psychiatrist Frantz Fanon (1925–61).

In the first two films, the only signs of life are the artists’ avatars. The third includes filmed footage of Blandy and Achiampong in matching tweed suits (the Gilbert & George of identity politics perhaps) alongside their families and a slender black dog. For the two artists (both fathers), the future is a central concern: lots of looking out to sea tells us so. But Finding Fanon is nonetheless defined by the material relics of the present: deserted cityscapes, empty dockyards, a concrete pillbox like those across the south coast of England.

Finding Fanon (2015–17), David Blandy and Larry Achiampong. Photo: Sam Garwood

These films were not made with Plymouth specifically in mind, but ripples of history run through them and out into the city beyond. ‘Water brought the Windrush to England in exchange for labour,’ we’re told over footage of a calm blue sea. ‘The Mayflower. The Cressy. The Duyfken. The empire and the endless wars continue to make endless movement through the times.’ These words serve as a reminder, that the Mayflower’s story is not a simple one: in Plymouth today, local dissenters are already criticising what they see as the ‘highly selective and sanitised’ version of history being told in schools and institutions. ‘The strongest fictions are winning,’ continues the film’s voice-over, aptly.

Art and exhibitions such as this have a crucial role to play in shaping Plymouth’s future, and in recent years the city has successfully applied for significant Arts Council England funding. Four major arts festivals are planned under the aegis of Horizon, a two-year programme of events and exhibitions awarded £635,000 in 2016 – beginning with the Atlantic Project in 2018. Another headline project is The Box, a £37 million cultural centre that will bring together six historic collections in time for 2020.

The Box, Plymouth, is due to open in 2020

The city is already home to a surprising number of smaller-scale venues, including Karst gallery and studios, Ocean Studios in Royal William Yard docks, and Radiant Gallery, which curates shows with children and young people. Counter Plymouth is an annual art book fair. Plymouth Platform offers mentoring schemes for early-career artists. Laura Edmunds, who has a studio at Karst, credits this scheme with helping her to manage the transition from recent graduate to professional artist. Technical support is available, too, and Edmunds’ forthcoming exhibition at Ocean Studios – part of the Plymouth Weekender festival (22–24 September) – involves new sound pieces alongside her stunning drawings. ‘Plymouth Platform has really changed the way I work as an artist,’ she says.

But the city is also receiving mixed messages, and several key organisations in the wider region have had their Arts Council funding cut completely. In 2014, Spacex in Exeter was removed from the Arts Council’s list of National Portfolio Organisations. Now, Arnolfini in Bristol and Plymouth Arts Centre have been cut too. This is potentially a major loss, not simply in terms of public programming but for the less visible work that the centre does to build a viable arts ecosystem in the city. ‘The loss of NPO status is a massive blow to our autonomy,’ says artistic director Ben Borthwick. ‘Our challenge is how to adapt to a new environment. Plymouth Arts Centre is still a critical piece of Plymouth’s cultural infrastructure.’

Laura Edmunds’ work on display at Karst gallery, Plymouth. Photo: Dominic Moore, 2017

The centre celebrates its 70th anniversary this year, and despite the recent funding news, continues to sit at the heart of numerous initiatives. In 2016/17 I undertook a residency there to help develop critical art writing capabilities in Plymouth, and in doing so discovered at first hand the city’s growing arts scene. (It was through this scheme that I met Edmunds and wrote a catalogue text for her September exhibition.) Many I spoke to attributed the city’s new cultural vitality to the arrival of the touring British Art Show 7 in 2011, which brought several different venues together to host it. They will join forces again this year for ‘We The People Are the Work’ (22 September–18 November), a multi-site exhibition showcasing artists such as Claire Fontaine and Ciara Phillips who have been working with communities across the city.

The future promises much for Plymouth. Alongside a burgeoning arts scene are numerous new developments. ‘Freedom is on the horizon,’ proclaims one of the many construction hoardings visible around town. But promises are not always kept. When the Mayflower bunting comes down, it is imperative that the tools (and funding) remain in place to ensure that Plymouth culture continues to flourish. In the closing shot of Finding Fanon II, the suited avatars of Achiampong and Blandy walk into the sea and the camera pans down into the water. Is that land visible on the horizon? Or am I just imagining things?

Finding Fanon (2015–17), David Blandy and Larry Achiampong.

‘David Blandy and Larry Achiampong: Finding Fanon Sequence’ is at Plymouth Arts Centre until 2 September 2017.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?