It was a city of narrow back alleys with bodies hanging out of doorways and rushes of steam blowing out through open windows. A snack of noodle soup eaten on plastic chairs was never far away. The mood was melancholic, a sad waltz played on a loop, the men wore dark glasses though there was no sunlight, and a woman in heels walked across dirty pavements without getting a speck of dirt on her beautiful silk dress. Wong Kar-Wai’s film In the Mood for Love (2000) projected this image of Hong Kong to a generation of moviegoers, creating in the popular imagination a vision of his city – so densely packed with people on a tiny section of an island covered by forests – as it was in the 1960s under British rule, but with an identity all of its own. Already when he was making the film in 1999 it was a nostalgic vision. It is dramatically more so today.

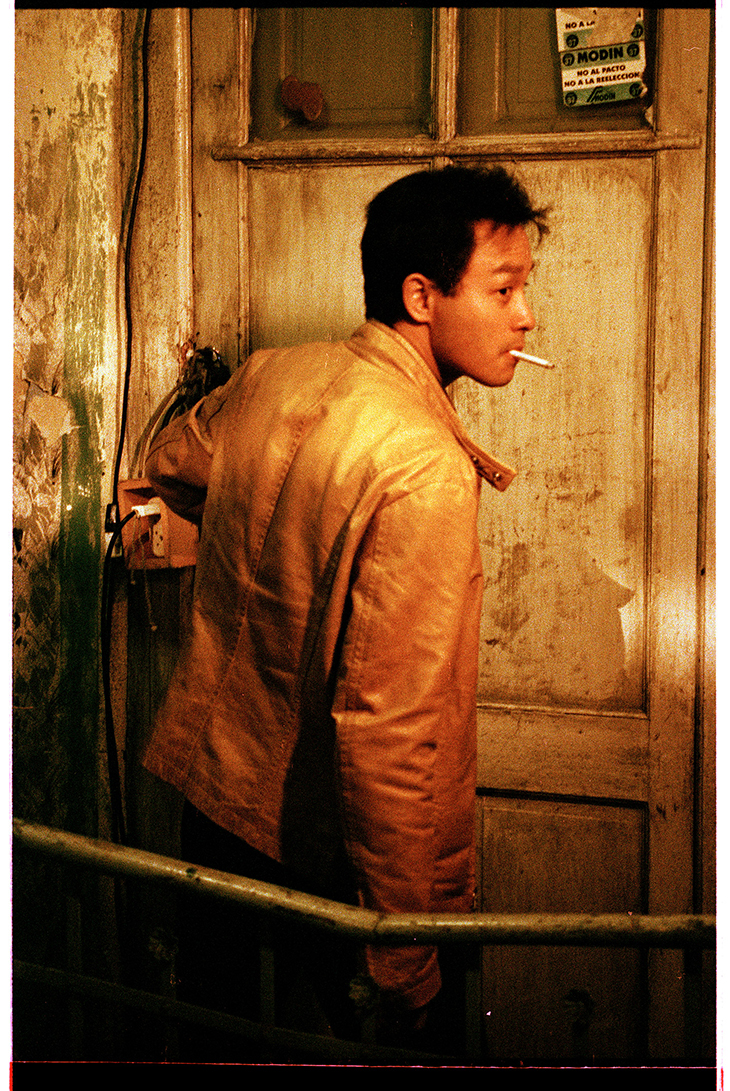

We are reminded of this with a jolt by an unusual item in the Sotheby’s Modern Art evening sales in October. To mark the 30th anniversary of his production company, Jet Tone Films, Wong Kar-Wai will be offering the short film In the Mood for Love – Day One, edited from unseen footage taken, as the title suggests, during the first day of shooting. The digital artwork will be sold as a non-fungible token (estimate 2m–3m HKD), which the auction describes as the first Asian film NFT. Other items on offer include the yellow leather jacket worn by Leslie Cheung in from Wong Kar-Wai’s feature Happy Together (1997); it comes with an estimate of 600,000–1.2m HKD. The following evening there will be a further sale of material including props, costumes and posters from the Jet Tone archives.

Wong Kar-Wai’s unseen footage offers an insight into the early versions of the characters, played by two of the city’s most celebrated actors, Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung. In the short film they appear in a quite different form from the finished movie, talking about the nature of love but without the charged rapport that we witness in the final cut. They are characters searching for definition – sketches of what they would eventually become. The appeal, then, of this material is similar to that of early drafts of a celebrated novel, or the sketches from an artist’s workbook that would evolve into a famous painting. ‘All creation originates from a single thought,’ Wong Kar-Wai writes in his statement for the upcoming sale:

Where did the first thought of In the Mood for Love originate from? Hard to say. What’s certain was that February 13, 1999 was the first day when I put that thought into action. The first day of every film production is like the first date with your dream lover – it is filled with fright and delight, like skating on thin ice. An arrow never returns to its bow; twenty years on, this arrow is still soaring.

Wong Kar-Wai’s list of notable films is not so long: Happy Together, In the Mood for Love and The Grandmaster, the last released in 2013. Other features display another side of the director, the one that makes flashy lipstick commercials. But this should not detract from the central place he holds in Hong Kong cinema. With In the Mood for Love he, more than any of his peers, raised the international profile of the city’s film industry, expanding its reputation beyond genre films and particularly action and martial arts movies from the likes of Bruce Lee, Johnnie To and Tsui Hark.

When I lived in Hong Kong in the early 2010s the world depicted in Wong Kar-Wai’s films was disappearing but it had by no means vanished. Walking home westward to Kennedy Town along the main road I would often turn my head to look down a side street from the main road and glimpse scenes that seemed like sudden flashes of In the Mood for Love, with the old streets full of conversations in Cantonese and neon lights, with little houses and sea cucumbers drying outside them. But it existed only in pockets and much of the populated part of the main island was packed with high rises and expats who worked in Wanchai by day and filled the bars and restaurants at night.

A new viewing of In the Mood for Love is also a sharp reminder that the city’s distinctive identity is fast being eroded under Chinese rule. Future generations in Hong Kong will likely regard Wong Kar-Wai’s film as a museum piece. After the Umbrella Revolution of 2014 and Beijing’s new security law, many activists are in prison or have retreated from political life. In the Mood for Love was always a nostalgic movie, but now it seems doubly so.

Wong Kar-Wai gets nostalgic

Maggie Cheng in never-before-seen-footage from Wong Kar-Wai’s ‘In the Mood for Love’ (2000). © Jet Tone Films

Share

It was a city of narrow back alleys with bodies hanging out of doorways and rushes of steam blowing out through open windows. A snack of noodle soup eaten on plastic chairs was never far away. The mood was melancholic, a sad waltz played on a loop, the men wore dark glasses though there was no sunlight, and a woman in heels walked across dirty pavements without getting a speck of dirt on her beautiful silk dress. Wong Kar-Wai’s film In the Mood for Love (2000) projected this image of Hong Kong to a generation of moviegoers, creating in the popular imagination a vision of his city – so densely packed with people on a tiny section of an island covered by forests – as it was in the 1960s under British rule, but with an identity all of its own. Already when he was making the film in 1999 it was a nostalgic vision. It is dramatically more so today.

We are reminded of this with a jolt by an unusual item in the Sotheby’s Modern Art evening sales in October. To mark the 30th anniversary of his production company, Jet Tone Films, Wong Kar-Wai will be offering the short film In the Mood for Love – Day One, edited from unseen footage taken, as the title suggests, during the first day of shooting. The digital artwork will be sold as a non-fungible token (estimate 2m–3m HKD), which the auction describes as the first Asian film NFT. Other items on offer include the yellow leather jacket worn by Leslie Cheung in from Wong Kar-Wai’s feature Happy Together (1997); it comes with an estimate of 600,000–1.2m HKD. The following evening there will be a further sale of material including props, costumes and posters from the Jet Tone archives.

Wong Kar-Wai’s unseen footage offers an insight into the early versions of the characters, played by two of the city’s most celebrated actors, Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung. In the short film they appear in a quite different form from the finished movie, talking about the nature of love but without the charged rapport that we witness in the final cut. They are characters searching for definition – sketches of what they would eventually become. The appeal, then, of this material is similar to that of early drafts of a celebrated novel, or the sketches from an artist’s workbook that would evolve into a famous painting. ‘All creation originates from a single thought,’ Wong Kar-Wai writes in his statement for the upcoming sale:

Where did the first thought of In the Mood for Love originate from? Hard to say. What’s certain was that February 13, 1999 was the first day when I put that thought into action. The first day of every film production is like the first date with your dream lover – it is filled with fright and delight, like skating on thin ice. An arrow never returns to its bow; twenty years on, this arrow is still soaring.

Wong Kar-Wai’s list of notable films is not so long: Happy Together, In the Mood for Love and The Grandmaster, the last released in 2013. Other features display another side of the director, the one that makes flashy lipstick commercials. But this should not detract from the central place he holds in Hong Kong cinema. With In the Mood for Love he, more than any of his peers, raised the international profile of the city’s film industry, expanding its reputation beyond genre films and particularly action and martial arts movies from the likes of Bruce Lee, Johnnie To and Tsui Hark.

When I lived in Hong Kong in the early 2010s the world depicted in Wong Kar-Wai’s films was disappearing but it had by no means vanished. Walking home westward to Kennedy Town along the main road I would often turn my head to look down a side street from the main road and glimpse scenes that seemed like sudden flashes of In the Mood for Love, with the old streets full of conversations in Cantonese and neon lights, with little houses and sea cucumbers drying outside them. But it existed only in pockets and much of the populated part of the main island was packed with high rises and expats who worked in Wanchai by day and filled the bars and restaurants at night.

A new viewing of In the Mood for Love is also a sharp reminder that the city’s distinctive identity is fast being eroded under Chinese rule. Future generations in Hong Kong will likely regard Wong Kar-Wai’s film as a museum piece. After the Umbrella Revolution of 2014 and Beijing’s new security law, many activists are in prison or have retreated from political life. In the Mood for Love was always a nostalgic movie, but now it seems doubly so.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

Walter Scott conjured up a playground for painters – and they fixed his fantasy of Scotland in place

The novelist may be little read today, but his fiction inspired an enduring, Romantic vision of the past

Making a scene – how the Victorians brought the past to life

Recreating scenes from famous paintings has been all the rage of lockdown, but it’s the Victorians who first played make-believe in earnest

Cavorting amid the ruins with Hubert Robert

The French artist’s obsessive portrayal of antiquity reveals his endless variety