Charles Saumarez Smith

‘I’ve had a good time. I’m perfectly happy to take a break.’ So says Charles Saumarez Smith, who steps down as secretary and chief executive of the Royal Academy of Arts at the end of 2018, a year in which the institution has celebrated its 250th anniversary by unveiling its remodelled (and much enhanced) premises in central London and by mounting an array of critically acclaimed exhibitions – and in which Saumarez Smith received a knighthood for his service to the arts. ‘It might seem mildly perverse not to mention that I appeared in yesterday’s honours,’ he wrote on his blog in early June, with characteristically wry self-effacement. The truth is that, in his quiet and likeable way, Saumarez Smith has had a transformative effect on the artistic life of Britain, directing two national museums and steering the RA towards the pre-eminence it now boasts among cultural institutions. He is a worthy recipient of the Apollo Personality of the Year Award for 2018.

Saumarez Smith joined the RA in September 2007; the following summer, David Chipperfield Architects won the competition to overhaul James Pennethorne’s building at 6 Burlington Gardens. The project soon evolved, as Chipperfield pressed the need to connect Burlington Gardens to Burlington House, and to forge a single coherent campus out of the RA’s disparate buildings and activities. From the outset, the planned redevelopment was a big draw for Saumarez Smith: ‘In a way my time at the RA has led to this year, because I came in partly to do the building project. That was part of the attraction of the job because I had always known about this building: I was aware that it was the last remaining unreconstructed building in the centre of London.’

This statement is telling; a reminder that, as an architectural historian by training, Saumarez Smith has always been something of an outlier among museum directors. He spent many years researching the design and fabric of Castle Howard, North Yorkshire, writing a PhD at the Warburg Institute on the subject that was later published as The Building of Castle Howard (1990). ‘I am sometimes criticised for being a museum director who is interested in building projects,’ he tells me. ‘I am. I was trained as an architectural historian and slightly bizarrely I’ve ended up in my professional career doing three big building projects.’

The first of those projects, at the National Portrait Gallery (where Saumarez Smith was director from 1994–2002), involved the construction of the Ondaatje Wing, which increased the museum’s public and exhibition space by 50 per cent; the second, once again working with Dixon Jones architects, saw the first phases of a masterplan implemented at the National Gallery (which he led from 2002–07). ‘My view is that actually it’s quite helpful having been trained as an architectural historian, because you can see and understand what changes to the ground plan will do to the organisation,’ he says. ‘When I was at the Portrait Gallery – not totally deliberately, but in practice – the architectural changes led to a revolution in the way the institution was perceived by the public, because they opened up the ground floor. That made it possible to do contemporary things and made it a place that 1.5 million people wanted to visit each year instead of 500,000.’

When Saumarez Smith joined the RA, it was ‘one of those places that had had endless schemes which never came to anything’, after the abandonment of projects by Michael Hopkins and Colin St John Wilson. Generally speaking, the public perception of the institution was as a popular exhibition space in grand, if somewhat shabby, premises off Piccadilly: ‘People would come in the front door, go up the stairs and go to a big exhibition. Then if they were lucky they would find their way to the ladies’ lavatories or the gents, both of which were fairly unpleasant. […] That was the experience of coming to the Royal Academy. Nobody knew that the Schools were underneath. I barely knew myself when I came here.’

Casts of Greek and Roman statues in the vaults of the Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photo: © Simon Menges

There was a clear imperative: to give due emphasis to living artists, to artistic process and to contemporary art. If this reflects the broader direction of travel in museums over the past decade – from didacticism towards a more discursive approach – then at the RA this trend finds its match in the history and structure of what is, in Britain at least, an unconventional institution. With its artist president (currently Christopher Le Brun) and council of academicians, this is an organisation that is run by artists, with a prestigious art school that offers its much soughtafter bursaries to a maximum of 17 students per year. So much the stranger, then, that by 2007 – as its former secretary David Gordon wrote in the Guardian at the time – it had effectively splintered into ‘two academies’.

Uniting the various constituencies of the RA, for the benefit of its activities and its public, has been both a collateral effect of the redevelopment process and one of its chief ambitions. The commitment to artists, to their voices and discussion of their work, is writ large in the new lecture theatre in Burlington Gardens, an airy auditorium that retains intimacy and a feel for tradition through its horseshoe-shaped seating. It is also evident in the opening up of the RA Schools and a gallery dedicated to work by their students, which visitors now pass through as they move between Burlington House and Burlington Gardens. ‘Teaching has always been part of the chemistry of the institution, but the public didn’t know it,’ says Saumarez Smith.

The Benjamin West Lecture Theatre at the Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photo: © Simon Menges

In this complex organisation, and at a time when it was reappraising itself, Saumarez Smith always regarded diplomacy as one of his main functions. He stated as much in an interview with a student newspaper soon after he assumed his role, and recalls being ticked off by one reader for his lack of ambition. But, as he insists, ‘having a mission to calm things down was ambitious, rather than passive’, given the widely reported fractiousness between different constituencies at the RA in the years before his arrival. His ‘four big constituencies’ are the general assembly of academicians, the council, the staff and the trustees, which ‘had a history of internecine warfare’: ‘Each of them was suspicious of the other and they spent a disproportionate amount of their time and energy fighting against one another in such a way that it damaged the public standing of the institution.’

The necessity of tact was inscribed in his job title. As the RA’s first ‘secretary and chief executive’, Saumarez Smith assumed the subordinate role of his predecessors while being invested with greater responsibilities for leadership – tasked with answering to the interests of the academicians, that is, while ‘running a big and quite complicated (and now increasingly expensive) organisation’. He admits that this has had its challenges, having ‘woken up to the fact that there’s a view that I could have been a bit more of a secretary and a bit less of a chief executive.’ But, as he emphasises, one of his greatest satisfactions in the role has been working closely with artists – a pleasure he first grasped at the NPG – and not least because the academicians of the 21st century tend to be far more attuned to the demands of management than their predecessors. ‘The post-1980 generation have had to make a living in quite a tough commercial world and they’re running what are sometimes quite large enterprises,’ he says, pointing out that the architect Nicholas Grimshaw, president from 2004–11, ‘was running a business with 200 people, so running the Royal Academy at that time was an exactly parallel operation’.

He has also understood how the academicians are a unique asset, that they set the RA apart from other institutions. ‘When I was interviewed,’ he recalls, ‘there were exhibitions by academicians at nearly every other institution in London. The Design Museum was doing Zaha Hadid, the Hayward was doing Antony Gormley, the Tate was doing Millais – but the Royal Academy was doing Byzantium.’ Another of the quirks of the RA is that – notwithstanding its royal appellation – it receives no public funding, so its exhibitions have always had to punch their weight when it comes to the bottom line. Staging contemporary art exhibitions in the main galleries had always been considered a commercial risk, for all that Norman Rosenthal had pushed the agenda during his colourful tenure as exhibitions secretary. Anish Kapoor’s exhibition in 2009, with its wax-blasting cannon and all, was ‘the beginning of a long road,’ says Saumarez Smith, who had raised extra funds with Kapoor and Grimshaw to ensure it could take place. ‘We got 270,000 people and it was a huge success.’

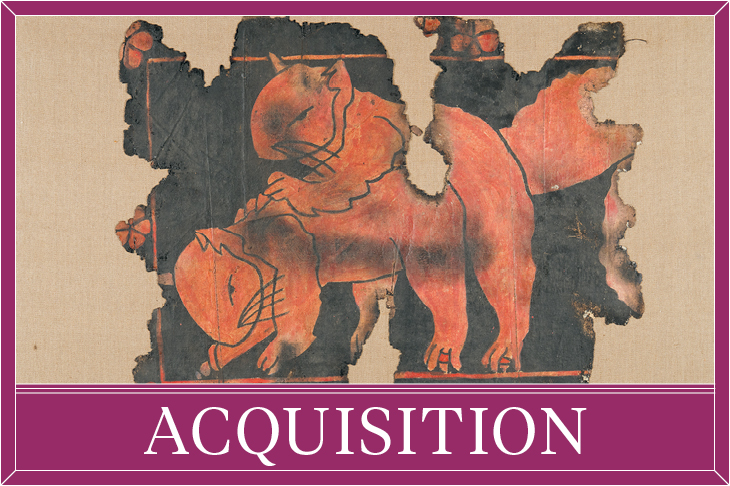

Under the aegis of Tim Marlow, artistic director since 2014, the exhibition programme at the RA has been stronger than ever. Its triumphs this year include the Apollo Exhibition of the Year, ‘Charles I: King and Collector’ and a jaunty Summer Exhibition curated by Grayson Perry. Saumarez Smith is particularly proud of ‘Oceania’ (until 10 December), which has brought the indigenous art of the region to far greater public consciousness, in the year that marks the 250th anniversary of Captain Cook’s first voyage. This is the type of exhibition that demonstrates and mobilises the international standing that the RA enjoys, despite its status as a private institution: ‘We tend to have much closer relations [than many institutions with] foreign governments, because we put on such big exhibitions. “Oceania” is very substantially supported by the governments of the territories whose work is represented here, because they see it as a way of promoting the identity of those regions, their cultures and practices.’

Installation view of the Gods and Ancestors room in the ‘Oceania’ exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, in 2018.

Has Saumarez Smith regretted not having time to curate exhibitions himself? ‘I would have liked to have written more,’ he says. ‘It’s no secret that I’m a frustrated academic.’ But while he has spent nearly 25 years in leadership roles, he has ‘always become interested in the history and culture of the institutions I’ve worked in – in a way that’s a legitimate thing to work on as a director’. Accordingly, in 2012, he published The Company of Artists: The Origins of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, and he has become fascinated by the history of the RA Schools, and ‘what art teaching has been, and how it has changed’. It seems apt that another of the features of the revamped RA is the Collection Gallery, in which a selection from its 50,000-strong collection is finally displayed – although as Saumarez Smith notes, from Hogarth’s day onwards, the RA has always had ‘an ambiguous relationship to the past of the institution and past practice’.

Perhaps there will be more time to write once he leaves the RA at the end of its annus mirabilis. Or perhaps not. Next year, Saumarez Smith will join the commercial gallery Blain Southern as a senior director. He describes the appointment as ‘a relationship rather than a hire’, having known its founders, Harry Blain and Graham Southern, for many years: ‘Almost the first transaction I made after I came here was leasing the whole of Burlington Gardens to them when they were running Haunch of Venison.’ There will be plenty of scope for working with artists in his new role.

Saumarez Smith is due at the opening of ‘Klimt/Schiele’. He leads me from his office in Burlington Gardens, through pristine galleries, across the new concrete bridge, down through the RA Schools, and through the vaults before we emerge in Burlington House. It is a route that Saumarez Smith’s time at the RA has made possible. The institution is open as never before, and he feels his work here is done. ‘After 10 years, you’ve probably done most of what you plan and expect to do,’ he says. ‘At that point it’s quite sensible to hand on the baton.’

Thomas Marks is editor of Apollo.

The Winners | Personality of the Year | Artist of the Year | Museum Opening of the Year | Exhibition of the Year | Book of the Year | Digital Innovation of the Year | Acquisition of the Year | View the shortlists

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.